BOOKS

Self-creation of a Mayfair laddie

Alastair Forbes

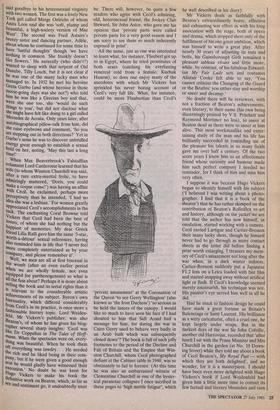

CECIL BEATON: THE AUTHORISED BIOGRAPHY by Hugo Vickers Weidenfeld, £16.95 Just 15 years after the state funeral of Winston Churchill, his old school's maga- zine recorded the death of 'one of Har- row's most distinguished and celebrated sons', Sir Cecil Beaton. On such a scale of comparison there cannot be counted a page too many in the 600 or so devoted by his infinitely painstaking young biographer to his life from cradle (and indeed even before that if the number concerned with the parents, grandparents and great- grandparents of someone he nevertheless classifies as 'that very rare creature — a total self-creation' — be taken into consid- eration) to grave. Hugo Vickers was vouchsafed only two brief meetings with his subject before being given the run of the abundant Beaton archives (including 145 closely written volumes of diaries which, at the outset at least, were clearly not kept for publication, since a youthful entry confided: 'I don't want people to know me as I really am but only as I'm trying and pretending to be.'). Even as the baked meats cooled, Vickers was setting off on half a decade of worldwide research into the personality and career of an immensely hard-working but always sing- ularly modest artist, stage-struck from childhood, who somewhat needlessly de- spised the fields of photography, fashion and design to which he found his talents being for the most part confined. 'He attached the least value to the things he did best' was the very fair and objective judgment of Louis B. Mayer's daughter, Irene Selznick, who loathed him.

As his nonpareil secretary and perfect friend of a quarter of a century, Eileen Hose, has rightly put it, 'he was unfulfilled at the end of his life. He was trying to find some way of expressing himself.'

Vickers sees it as a tribute to Cecil that 'his friends (and indeed the occasional foe) enjoy talking about him'. The list of the some 250 persons who have done so to him contains both categories, sometimes one masquerading as the other, as well as a number of walk-on extras whose encoun- ters with le cher Maitre were seemingly as brief as their acquaintance remained slight.

I do not share Hugo Vickers's surprise that the grandson of a coal-miner should have turned into Ronald Firbank or the grandson of a blacksmith into Cecil Beaton, but there is no doubt that the latter's preoccupations with the crass com- plications of England's ghastly class- consciousness weighed heavily on his youth. When he was little he cherished the illusion that his beloved mother was 'an important Society figure' and 'he was bitterly disappointed to discover that she was not, but resolved to improve her'. He was 23 by the time he was able to record: 'For Mummie to get in Tatler! Lovely. This is what I had been trying for for years!' (It is fair to add that when, during the war, he photographed 2,000 Wrens 'fat and old, young and thin', all prayed it would be in the Tatler.) At 23, too, he found it neces- sary to qualify the statement that `Daddy is fairly nice: he's really sweet. He's very good-natured' by adding that he 'is getting an infirm and annoying old fool and rather a common fool at that.' At his father's death nine years later he 'shuddered to think how irritating he must have found his pretentious children with their snobbery and social climbing'. Had Ernest Beaton but lived a year or two longer he would have found Cecil become virtually a re- vered Establishment figure and accepted as 'one of us' by old-style aristos as well as the 'déclassé' kind lately seen by Lord Annan as the only ones prepared to put up with Evelyn Waugh, Cecil's perennial persecu- tor from pre-prep-school days. Mount Beaton was now the peak towards which climbers on both sides of the Atlantic and Channel were actually setting their social sights. Cecil himself, once safely arrived, cast aside snobbery, along with the arri- visme that had been needed on his journey.

Another handicap, less easily surmount- able than any embarrassment at real or imagined parental shortcomings, was the fact that, as he noted ('what I am now writing is tremendously private and I should be horrified if some friend or relation read it') in undergraduate days: 'I'm really a terrible, terrible homosexual- ist and try so hard not to be.' Yet, compared to Tom Driberg and Evelyn Waugh at Lancing, at Harrow he had been chastity itself.

'Wretched people thought just because I was frightfully pretty and luscious that I must be a little tart and just dressed nicely to get off with people. . . Most people were frightfully naughty and used to go to bed with tons of people but I didn't.' He seems to have forsaken soppy mooning for more physical jerks in the hay only once, with another clesoeuvre Harrovian on a Field Day. Going the whole hog he evidently found 'cheap and horrid. . . it's so much nicer just to be affectionate and ordinary and sleep in the same bed but that's all. Everything else is repulsive to me.' His libido's thermostat was apparent- ly set low for a man of his age. Yet any decent heterosexual, of either sex, ought to be moved, even shamed by what he set down in 1966 on the publication of the Wolfenden Report, whose recommenda- tions were not to be put into effect until, years later, brave and honest 'Boofy' Arran, that unforgettably lovable eccen- tric, was from the Lords to sting the pussy-footing Commons into action.

Of recent years the tolerance towards the subject has made a nonsense of many of the prejudices from which I myself have suffered acutely as a young man. It was only compara- tively late in life that I would go into a room full of people without a feeling of guilt. To go into a room full of men needed quite an effort. With success in my work, this situa- tion became easier. But when one realises what damage, what tragedy has been brought on by this lack of sympathy towards a very delicate and difficult subject, this should be a time of great celebration. - Selfishly I wish that this marvellous step forward could have been taken at an earlier age. It is not that I would have wished to avail myself of further licence, but to feel that one was not a felon and an outcast could have helped enormously during the difficult young years.

In fact Cecil's longest and most abject homosexual attachment, to Peter Watson, the very rich young Maecenas (Horizon's backer and the dedicatee of Cyril Connolly's The Unquiet Grave) was neither requited nor consummated. Few of his affairs could be deemed gay in the old sense of that once delightful word, and in New York call-boys would come and go as required, just like the call-girls to-ing and fro-ing between the apartments of his rich, jet-set Manhattan acquaintances. He even once succeeded in seducing a very 'beautifully proportioned boxer, after first listening to his boastful stories of his stud performances with the ladies and of his avoidance up till then of anY hanky-panky with pansies, but 'it was not worth the bother'. In 1963, however, a handsome 6ft-4in-tall American, half his own age, came into his life and gave him a year of happiness, despite his sense of humour being a little on the Californian side, that is to say rather short. In one week in 1929 he had enjoyably said goodbye to his heterosexual virginity With two women. The first was a lively New York girl called Marge Oelrichs of whom Anita Loos said she was 'soft, plump and beautiful, a high-society version of Mae West'. The second was Fred Astaire's breezy sister and dancing partner, Adele, about whom he continued for some time to have 'lustful thoughts' though 'we have nothing in common. She frankly doesn't like flowers.' He naturally (who didn't?) wanted to sleep with that serpent of Old Danube, Tilly Losch, but it is not clear if he was one of the many lucky men who managed to. In 1932 he met his heroine Greta Garbo (and whose heroine in those rnovie-going days was she not?) who told bun he was like a Grecian boy and that, were she one too, she 'would do such things to you', but did not disclose what She might have felt like doing to a girl called Mercedes de Acosta. Only years later, after autobiographical pillow-talk from him, did she raise eyebrows and comment, `So you are stepping out in both directions?' Yet in Garbo's arms he was to discover unbridled ,_energy great enough to establish a sexual hold on her, noting, 'May this last a long time!'

When Max Beaverbrook's Falstaffian columnist Lord Castlerosse learned that his Wife (to whom Winston Churchill was said, after a rare extra-marital frolic, to have admiringly muttered, 'Doris, you could make a corpse come!') was having an affair With Cecil, he exclaimed, perhaps more Perceptively than he intended, 'I had no idea she was a lesbian.' For women greatly aPpreciated Cecil's accomplishments in the sack. The enchanting Coral Browne told Vickers that Cecil had been the best of lovers, of whom she had nothing but the haPpiest of memories. My dear Greek friend Lilia Ralli gave him the same '3-star, Worth-a-detour sexual references, having alSO reminded him in life that 'I never feel more completely entertained as by your Company, and please remember it'. Well, we men are all at first bisexual in the womb (after an even earlier period When we are wholly female, not even equipped for parthenogenesis) so what is qu the fuss about? Perhaps it is more about Selling the book and its serial rights than it is relevant to the considerable artistic ac.hievements of its subject. Byron's own Sexuality, which differed considerably 'min Cecil's in its practice, is once more a fashionable literary topic. Lord Weiden- feld, Mr Vickers's publisher, was also Beaton's, of whom he has given his biog- rapher several sharp insights: 'Cecil was hke Dr Coppelius in The Tales of Hoff- '1P1. When the spectacles were on, every- thing was beautiful. When he took them off everything was tawdry. . . He needed the rich and he liked being in their com- ParlY, but if he were given a good enough seat he would gladly have witnessed their execution.' No doubt he was keen for Hugo Vickers to make his book the definitive work on Beaton, which, as far as sex and sentiment go, it undoubtedly must be. There will, however, be quite a few readers who agree with Cecil's admiring, old, heterosexual friend, the Jockey Club Steward, Sir John Astor, who gave me his opinion that 'private parts were called private parts for a very good reason and I am sorry to see them so much indecently exposed in print'.

All the same, just as one was interested to learn what, for instance, Flaubert got up to in Egypt, where he tried prostitutes of both sexes (catching his everlasting venereal cold from a female, Kuchuk Hanem), so does one enjoy many of the anecdotes with which Mr Vickers has sprinkled his never boring account of Cecil's very full life. What, for instance, could be more Flaubertian than Cecil's 'private amusement' at the Coronation of the Queen `to see Gerry Wellington' (also known as 'the Iron Duchess') `so serious as he held the lances of the canopy. I would like so much to have seen his face if I had shouted to him that Sidi Azaid had a message for him, for during the war in Cairo Gerry used to behave very badly in an Arab bath which was subsequently closed down'? The book is full of such jolly footnotes to the period of the Decline and Fall of Britain and the Empire that Win- ston Churchill, whom Cecil photographed defiant at the Cabinet table in 1940, was so obstinately to fail to foresee. (At this time he was also an embarrassed witness of Clementine Churchill in one of the hyster- ical paranoiac collapses I once ascribed in these pages to 'high mettle fatigue', which he well described in his diary).

Mr Vickers deals as faithfully with Beaton's extraordinarily brave, effective and exhausting war effort as with his long association with the stage, both of opera and drama, which stopped short only of the fulfillment of his one great ambition, which was himself to write a great play. After nearly 30 years of adjusting its nuts and bolts, his Gainsborough Girls remained a pleasant tableau vivant and little more, while, by contrast, of his fabulous Edward- ian My Fair Lady sets and costumes Alistair Cooke felt able to say, 'You cannot criticise the Changing of the Guard or the Beatles: you either stay and worship or sneer and decamp.'

No doubt there will be reviewers, with not a fraction of Beaton's achievements, even literary, to their name (his own being discerningly praised by V.S. Pritchett and Raymond Mortimer no less), to sneer at Beaton dead as there were to sneer at him alive. This most workmanlike and enter- taining study of the man and his life has brilliantly succeeded in reminding me of the pleasure his talents in so many fields gave me over half a century. Of the two score years I knew him as an affectionate friend whose curiosity and humour made him such perfect company I needed no reminder, for I think of him and miss him very often.

I suppose it was because Hugo Vickers began to identify himself with his subject CI believed I was writing about a photo- grapher. I find that it is a book of the theatre') that he has rather skimped on the contribution of Beaton's Rolleiflex to art and history, although on the jacket we are told that the author has now himself, in emulation, started working with a camera. Cecil envied Lartigue and Cartier-Bresson their many lucky shots, though he himself never had to go through as many contact sheets as the latter did before finding a print worth enlarging. I treasure my mem- ory of Cecil's amazement not long after the war when, in a dark winter indoors, Cartier-Bresson suddenly put a Japanese F1.2 lens on a Leica loaded with fast film and started snapping away without artifical light or flash. If Cecil's knowledge seemed merely amateurish, his technique was not. His painter's eye served him well in all he did.

Had he stuck to fashion design he could have made a great fortune as Britain's Balenciaga or Saint Laurent. His brilliance as a witty caricaturist, often a cruel one, he kept largely under wraps. But in the darkest days of the war Sir John Colville, another old Harrovian, recorded that 'after lunch I sat with the Prime Minister and Mrs Churchill in the garden (at No. 10 Down- ing Street) while they told me about a book of Cecil Beaton's, My Royal Past — with which they are both delighted', and no wonder, for it is a masterpiece. I should have been even more delighted with Hugo Vickers's book if Lord Weidenfeld had given him a little more time to correct its few factual and literary blemishes and turn it into a work of art — but perhaps one should not complain of a very well-edited and illustrated volume that, aside from deserving great success here and in Amer- ica, strikes me as being the first for a long time from the Clapham firm that does not almost immediately come apart at the seams and spill its many misprints on to the floor. I was much struck by the characteris- tically generous letter Duff Cooper, who always admired Cecil's `guts', wrote to him after witnessing, in a company of friends that included myself, the first night of his perhaps rather unjustly ill-fated Gains- borough Girls, and I need only alter one word of it in quoting it back to Mr Vickers: `I thought it a good book and I enjoyed it. What is more, I am sure you can write a better one.'

Previous page

Previous page