MR LAWSON'S SECRET INFLATION

.Britain is experiencing its biggest-ever credit boom. Tun Congdon argues that if inflation is to be avoided the

Bank of England must be freed from political control

MUCH has gone wrong with the manage- ment of the British economy in the last two Years. The growth of credit and money is tca high, the economy is expanding too quickly and interest rates are too low to prevent the return of inflationary press- ures. Indeed, the scale of the present credit boom is without precedent. In terms of the amount of money being lent by both banks and building societies, it is larger than the notorious Heath/Barber boom of the early 1970s. The main message of the latest phase of financial ex- cess, so depressingly similar to many other episodes in the post- war Period, is simple: monetary policy is too serious to be left to Politicians. Britain should follow West Ger- many's example by giv- ing the Bank of England

as much independence from government as is currently enjoyed by the Bundesbank.

That, in brief, is the

argument of this article. It is an expression of

deep scepticism about the ability and willing- ness of British govern- ments to conduct finan- cial Policy in a consis-

tent, stable and non-inflationary way. Their monetary performance over the last 40 years has been too unreliable for them

to be trusted in future. Alternative arrangements, which as far as possible take Macro-economic policy outside the politic- al domain, are needed. True enough, three or four years ago such scepticism seemed unjustified. Mrs Thatcher's first term had succeeded in bringing inflation down from over 20 per cent in early 1980 to under five per cent by mid-1983, while confidence in the perma- n ence eof responsible financial policies was buttressed by targets for monetary growth and public sector borrowing in the Medium-Term Financial Strategy. There appeared to be a consensus that monetary policy had been anti-inflationary and would remain so, at least as long as the Conservatives stayed in power.

The breakdown of that consensus has a complicated story, in which many of the details are technical. But the main points are not particularly abstruse. They should not be allowed to frighten away readers who have a hunch that the subject is important and deserves to be understood, but are sometimes deterred by commenta- tors who make it seem more confusing that it actually is.

One of the most important debates in British monetary policy in recent years has related to the significance of narrow money as compared to broad money. Narrow money consists of notes and coin held by people and companies, plus (on some definitions) bank deposits which can be drawn on without notice; broad money consists of notes and coin, and all bank deposits. Holdings of bank deposits are many times larger than holding of notes and coin.

When the first monetary targets were announced by Mr Healey in 1976 and again after 1980 in the early versions of the Medium-Term Financial Strategy, monet- ary policy was stated in terms of broad money. Indeed, for a few years the phrase, `the money supply', was virtually synony- mous with broad money. The reliance on broad money could be explained partly by the reasonably close connection it had had with total spending in the economy in the 1960s and 1970s.

This approach had a very important practical result. Bank deposits make up 90 per cent of the broad money total, but banks can expand their deposits on one side of the balance sheet only if they can expand their loans on the other. A target for broad money therefore contains, at least by implication, a limit on the growth of bank credit. In consequ- ence, the period of broad money targets in- volved careful monitor- ing of credit to both the public and private sec- tors. Credit to the public sector was curbed by re- ducing the Govern- ment's budget deficit and credit to the private sector by maintaining an appropriately high level of interest rates.

This system of monetary control was a success. Contrary to all the sneers in the media, and despite many awkward teething-troubles in its implementation, it worked, on the only test that really mat- tered: it brought a sharp fall in inflation to a country which had seen rising inflation, comparing one cyclical peak with another, for over 20 years. In 1984. and 1985 there was no need to change it. It could — and should — have been left alone.

However, officials at the Treasury and, to a lesser degree, at the Bank of England, were concerned about certain changes in the relationship between broad money and money national income. Control over broad money may have achieved lower inflation, but they were mystified that a particular growth rate of broad money seemed to be associated with less inflation in the 1980s than it would have been in the 1970s. There was enough of a puzzle for them to recommend to Mr Lawson that the Government shift its attention towards narrow money. Mr Lawson accepted their view and abandoned broad money at some stage in the middle of 1985.

This may have seemed, to those uniniti- ated in the subtleties of the monetary management, a petty detail in the political life of the nation, a point of some interest to the financial artisans who work the parish pumps of Lombard Street and Threadneedle Street but of none to the more dignified citizens of Westminster and Whitehall. In fact, the move away from broad money is fundamental to explaining both subsequent developments in the eco- nomy and the Conservatives' success in the general election. With broad money targets no longer the focus of policy, the Government was excused from the need to limit the growth of bank credit. Whether by accident or by design, Mr Lawson had set the scene for the largest boom in private credit this country has ever seen. It is this boom which more than anything else, has been responsible for the recent upturn in the economy, for the sense of well-being undoubtedly felt by the major- ity of voters (particularly those owning homes) and for the Government's re- election.

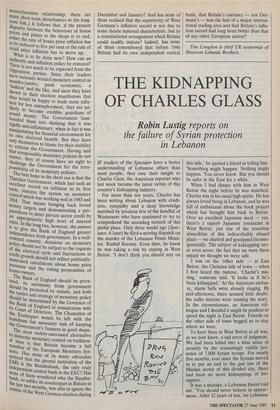

The Government may not have realised, as preparations were made for the credit boom, just how spectacular it would prove to be. The growth of private credit had been high throughout the early 1980s, largely because of the removal of a variety of restrictions on the banks and other financial institutions, but it was not out of control. Sterling bank lending to the pri- vate sector was steady at about £13 billion in 1982, 1983 and 1984, with the growth rate under 20 per cent a year and falling. After adjustment for inflation, the amount of bank lending was appreciably less than in the Heath/Barber boom of 1972 and 1973. But in 1985 and 1986 the position changed radically. Bank lending doubled in just two years to reach £30 billion, a level far higher than ever before in nominal terms and about 25 per cent more in real terms than the previous peak of 1972.

The extra credit was not sprinkled evenly over all parts of the economy, but channelled particularly into the housing market. A substantial portion of the record bank lending total was accounted for by mortgage credit, as the banks tried to gain market share from the building societies. Nevertheless, building society lending was also exceptionally strong.• As the table shows, the expansion of the building societies, business has been more than of the banks' since the Thatcher Government came to power. In real terms building societies' net mortgage advances were not just greater in 1985 and 1986 than in 1972 and 1973, but virtually twice as high.

These figures are both an eloquent tribute to the Thatcher Government's de- termination to promote home-ownership and a disturbing commentary on the conse- quent problems of financial management. It was almost as if, once Treasury ministers had liberalised the market in mortgage finance and so enabled more people to buy a house, they felt obliged to make people happy with their investment. Since the start of the credit boom in mid-1985 the national rate of house price increase has gone up from under ten per cent a year to almost 15 per cent, while in some parts of London property prices have doubled. It 15 not coincidence that those areas of the country with the highest proportion of owner-occupied housing were the same areas which saw a swing towards the Conservatives in the election. As in the Heath/Barber boom of the early 1970s, the explosion in credit has led to accelerated growth of broad money. For some time now the money supply has been expanding at an annual rate of about 20 per cent. There may be some doubts about the precise nature of the link between broad money and money national income, but that does not mean there is no link at all. It is almost incredible that Mr Lawson who now as Chancellor of the Exchequer is so insouciant about the fastest monetary growth for 15 years is the same Mr Lawson who as Financial Secretary to the Treasury in June 1980 declared that 'in order to reduce the inflation rate on anything more than an ephemeral basis it is necessary to reduce the rate of monetary growth'. As, Professor Charles Goodhart has remarked in the latest Gerrard & National Economic Viewpoint, The capacity of the present Conservative government, and of the Treasury, to move from the (invalid) viewpoint that the growth, of broad money is an exact determinant (in" the growth of nominal incomes to the Oa; valid) viewpoint that the growth of broad money has no relationship at all with the growth of nominal incomes is staggering with respect both to its speed and to the comre' hensive nature of the intellectual somersault involved.

Those who are perplexed by broad money might like to reflect on the more accessible idea that house prices and the general price level tend to move together over periods of several years. (As with the

The growth of credit over the last 20 years

Bank lending, in sterling, to UK private sector -£m., current prices Net mortgage advances by building societies -em., current prices GDP deflator (factor cost, expenditure data) 1980 = 100 Bank lending, in sterling, to UK private sector -£m., 1986 prices Net mortgage advances by building societies -£m., 1986 prices

1967 511

823 22.9 3,182 5,125

1968 538

860 23.7

3,237

5,175

1969 429

782 24.5

2.497

4,552

1970 678

1,088 26.4

3,662

5,877

1971 1,776

1,576 29.3

8,644

7,670

1972 5,511

2,215 32,3

24,330

9,779

1973 5,671

1,999 34.8

23,238

8,191

1974 3,734

1,490 40.7

13,083

5,220

1975 -367

2,768

51.8 -1,010

7,620

1976 3,081 3,618 59.3 7,409

8,700

1977 3,492 4,100 66.6 7,477

8,779

1978 4,710 5,115 74.7 8,991

9,764

1979 8,573 5,271 84.2 14,519

9,078

1980 9,622 5,722 100.0 13,721 8,160 1981 8,633 6,207 110.3 11,161 8,025 1982 13,055 8,147 118.0 15,777 9,845 1983 13,628 10,928 124.6 15,597 12,507 1984 13,479 14,572 130.4 14,740 15,935 1985 19,839 14,711 138.5 20.426 15,146 1986 30,005 19,072 142.6 30,005 19,072

Source: Financial Statistics, Economic Trends money/incomes relationship, there are many short-term disturbances to the long- term link.) It follows that, if the present disparity between the behaviour of house prices and prices in the shops is to end, either the rate of house price inflation has to be reduced to five per cent or the rate of retail price inflation has to move up. What is to be done now? How can an authentic anti-inflation policy be restored? There is not much to be expected from the Opposition parties. Since their leaders have variously derided monetary control as mumbo-juinbo, punk economics, a fashion' and the like, and since they have shown in their election manifestoes that infla- tion would be happy to trade more for less unemployment, they are un- likely to become credible guardians of sound money. The Government bam- boozled them into thinking that it was rigidly anti-inflationary, when in fact it was manipulating the financial environment for its own electoral benefit. But they have only themselves to blame for their inability to criticise the Government. Having said that irresponsible monetary policies do not matter, they of course have no right to challenge the Government for the irres- ponsibility of its monetary policies. The best hope in the short run is that the Thatcher Goverrunent, which had such. an excellent record on inflation in its first term, restores the system on monetary control which was working well in 1983 and mo 1984. That means bringing back broad ney targets and demonstrating a pre- paredness to deter private sector credit by an appropriately high level of interest rates. In the long run, however, the answer is to give the Bank of England greater ep ndendence from government. In a well- ordered country, decisions on monetary Policy should not be subject to the vagaries of the electoral cycle and fluctuations in credit growth should not reflect politically- motivated calculations about house price increases and the voting propensities of home-owners. The Bank of England should be priva- tised, its autonomy from government should be protected by statute, and both the tactics and strategy of monetary policy should be determined by the Governor of the Bank of England in consultation with its Court of Directors. The Chancellor of the Exchequer would be left with the humdrum but necessary task of keeping the Government's finances in good shape. The most widely-canvassed alternative to domestic monetary control on tradition- al lines is that Britain become a full ember of the European Monetary Sys- tens, Has none of its many advocates noticed that the pivotal institution of the EMS is the Bundesbank, the only truly independent central bank in the EEC? Has none of them wondered why the Bundes- bank, so unlike its counterpart in Britain in the last two months, was able to ignore the course of the West German election during December and January? And has none of them realised that the superiority of West Germany's inflation record is not due to some innate national characteristic, but to a constitutional arrangement which Britain could readily imitate? Indeed, has none of them remembered that before 1946 Britain had its own independent central bank, that Britain's currency — not Ger- many's — was the hub of a major interna- tional trading area and that Britain's infla- tion record had long been better than that of any other European nation?

Tim Congdon is chief UK economist of Shearson Lehman Brothers.

Previous page

Previous page