THE SECOND BATTLE OF COVENT GARDEN

Gavin Stamp weighs up the

opposition to the redevelopment of the Royal Opera House

OLD soldiers refighting old battles can be a little pathetic. There is something of this in the current campaign being waged by the Covent Garden Community Associa- tion against the Royal Opera House's expansion and redevelopment scheme. Old activists are reliving the heady days of the early 1970s, when Covent Garden, both physically and as a 'community', was threatened with annihilation by the GLC's redevelopment proposals. The preserva- tion of Covent Garden was a famous victory, of immense importance in turning the tide against the destruction of historic urban fabrics.

But times have changed and so, whether for better or for worse, has Covent Gar- den. The new 'community' which is so anxious to fight new commercial develop- ment seems to consist more of new public relations agencies and successful tourist shops than old residents, and their enemy — the Royal Opera House — has a respectable ancestry on the site which goes back to the 18th century. The trouble is that the Opera House is going in for speculative office development, and offices seem to be irredeemably wicked. There are dark hints that the Opera House is in league with property developers, and accusations that it is selling land given to it by the nation (false — in so far as it will be leases that are sold), What, unfortunately, is clear is that help cannot any longer be expected from the government, whatever its colour. The Con- servative Party seems disinclined to subsi- dise any worthwhile enterprise while the Labour Party, despite its commitment to the 'Arts', now evidently regards opera as `elitist' and not as worthy of help as community arts, black arts, etc.

The Board of the Royal Opera House has responded to this state of affairs in a very responsible way by deciding to try and raise the money needed itself and become self-sufficient. The solution adopted was to exploit its resources to generate an income. With the advice of three property develop- ers on its development committee, notably

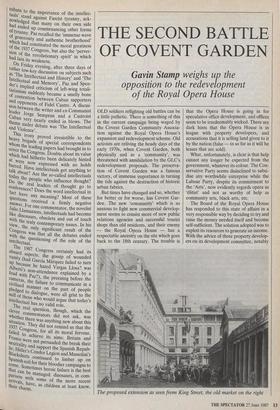

The proposed extension as seen from King Street; the old market on the right

its chairman, Christopher Benson, it has been decided to build lettable commercial spaces on some of the Opera House's land. The sites in question are in Long Acre and, more importantly, to the south of the Opera House. This largely vacant space, bounded by the Covent Garden Piazza, Russell Street and Bow Street, was given to the Opera House by the government in 1975 for future expansion.

The Opera House has also behaved well in choosing an architect. While the Trus- tees of the National Gallery were making a farce of their own extension project, the Opera House, after a limited competition in 1984, chose Jeremy Dixon, a youngish architect with a good if largely untried reputation, to work with William Jack of the Building Design Partnership, an ex- perienced commercial firm. The resulting designs, unveiled in 1986 and revised ear- lier this year, fully justify the choice.

The brief was formidable. As well as lettable space on the perimeters of the site, the Opera House needs enlarged backstage space, a scenery store, accommodation for the Royal Ballet Company (at present exiled in Baron's Court), new changing rooms, offices and a music library, and, of course, enlarged foyers and other public spaces. On the confined site, the architects have had to perform a three-dimensional jig-saw, coping with the conflicting move- ments of arriving scenery and other goods, backstage hands and the general public.

The only space for new foyers is im- mediately to the south of the existing Opera House auditorium. Here Dixon has designed an appropriately grand oval double-flight staircase which will rise five storeys and so end the intolerable segrega- tion between the cheaper upstairs amphitheatre seats and the main body of the house. Furthermore, this foyer and staircase will be accessible from the Piazza, thus restoring an important entrance to the Opera House which was lost when Smirke's theatre was burned in 1856.

In the Piazza, which desperately needs to be completed, Dixon has chosen not to continue the arcaded elevations of Henry Clutton's Victorian buildings — nothing is now left of the original houses by Inigo Jones — but to have stone-faced classical elevations above a Doric colonnade, with covered vaulted spaces behind inspired by the Uffizzi. At the top, above the cornice, is an open loggia to be used, in part, by Opera House patrons during intervals an inspired idea.

The proposed facades in Russell Street, Bow Street and Long Acre, are different in character and, following criticism, have been modified. They are now to be in stripped classical manner in brick and stone and they are highly sophisticated, well detailed elevations of serious architectural quality. What I find fascinat- ing about them is that Dixon has been looking at eary 20th-century masters like the great Slovene, Pleenik, as well as our own Charles Holden — men who made tradition come to terms with modern con- ditions with resourcefulness and style. In comparison with the illiterate vulgarity of much Post-Modernism or the unimagina- tive sterility of our neo-Palladians, Dixon's use of precedent is intelligent, creative and appropriate to the site.

Ihave some reservations about the details of Dixon's architecture, but I can- not sympathise with the criticism that his buildings are bad because they are, in part, commercial. Office workers have souls and can contribute to the life of Covent Gar- den, while Dixon's buildings have shops at street level and follow street lines in a proper, urban manner. What is most wor- rying is the required demolition of build- ings, both listed and unlisted, in Russell Street and Long Acre. They are small, humble structures of appropriate character whose passing I lament, but for a grand statement by a great national institution, sacrifices may, for once, be justified.

For the Covent Garden Community Association and its allies, the Residents and Tenants Association and the Soho Housing Association, such sacrifices are not at all justified, especially as the new buildings are to be commercial. The opposition condemns, with some justice, the fact that only one third of the land acquired in 1975 and held in trust 'with the intention of safe-guarding the interests of the Royal Opera House and possible ex- tensions' is to be physically occupied by the Opera House. Furthermore, the Covent Garden Project, by building yet more offices and no housing, goes against the recommendations of the statutory Covent Garden Action Area Plan. But most damn- ing, perhaps, is the observation that the redevelopment scheme has no provision for either a second auditorium or accom- modation for the Royal Ballet School, both of which were regarded as essential when the Opera House unveiled its first develop- ment scheme in 1980.

Last week, the opposition unveiled its own alternative development scheme, de- signed by Jim Monahan, a stalwart survi- vor of the battles of the 1960s. Naturally this plan involves retaining most of the existing buildings on site and provides housing as well as a limited amount of office accommodation and a luxury hotel in the Piazza (where the old Tavistock Hotel used to stand). As architecture, the scheme is trite and amateur, but there are some interesting ideas in this alternative scheme which are not to be dismissed lightly. One is the abandonment of the unnecessary and destructive underground car park — re- quired by Westminster City Council — and spending the money instead on a new escalator link from the Piazza to Covent Garden station — a brilliant idea which will relieve the pressure on the intolerably crowded Edwardian tube station and assist pedestrian movement. Monahan also tack- les the problem of the Floral Hall, the now mutilated cast-iron structure erected to the south of the Opera House when E. M. Barry rebuilt it after the 1856 fire. Dixon keeps only the Bow Street elevation, with its arched vault restored; Monahan recon- structs the building to act as a public foyer facing an open amphitheatre in the centre of the Piazza-Russell Street-Bow Street block — a bold architectural and theatrical gesture.

The reaction of the Royal Opera House to this alternative scheme is simply to dismiss it as unrealistic. Its own scheme, costed at about £100 million, will apparent- ly still have a shortfall of £23 million, even after commercial lettings have been achieved. The deficit in the alternative scheme will, of course, be infinitely grea- ter. What is profoundly depressing is that the merits of all the schemes are evaluated almost entirely in terms of money. The Opera House Board considers that there is no alternative to commercial redevelop- ment of part of the land, but one wonders if alternatives have been seriously consi- dered. George Whyte, a stalwart of the Opera and a retired high-powered businessman, argues that they have not and complains that the Board has dismis- sed his own suggestions for an aggressive commercial exploitation of the Opera House's reputation. But the most worrying criticisms of the Covent Garden Scheme — which have received little publicity — come from within the theatrical world. The Theatre Trust, created by Act of Parliament in 1976, is not concerned with architectural or social issues but that a modernised Opera House 'will give good service into the second half of the 21st century'. While praising much of the scheme, the Trust feels that the Opera House will be too confined by the commercial develop- ments, rendering future alterative back- stage difficult or impossible, and als°, considers that the proposed new foyers and staircase are simply not large enough. In the middle of all this argument is the heroic figure of Jeremy Dixon, who has struggled to keep the commercial volume to a minimum and who has tried to cool- promise without reducing the quality of his architecture. I am sure he is the right architect for this job but I have a worrying suspicion that he may be working to an unsatisfactory brief. Westminster City Council will consider granting planning permission to the Royal Opera House Covent Garden Project on 30 June. In view of the serious arguments raised about its very nature, perhaps it ought to be examined at public inquiry although the issue of whether a national opera house enjoying royal patronage should have to be a property developer to survive should really be a matter for Parliament. When the second theatre on the site was destroyed in 1856, it was almost not rebuilt at all and then econo- mies were made: perhaps the present Opera House board is just sensibly fatalis- tic about the instrinsic official philistinism of this country. Certainly the future of an opera house of international stature would not be decided this way in Paris, or Munich, or Vienna, or Milan.

Previous page

Previous page