THE KURDS OF HACKNEY

Michael Trend meets

part of a wave of refugees

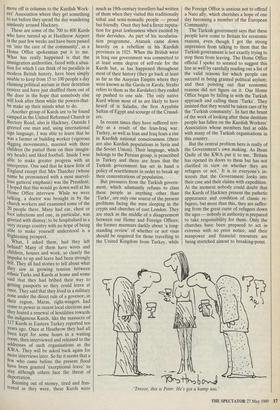

EVERY evening for the past two weeks a party of some 30 or so young Kurdish men, none of whom speaks English, have knock- ed on the door of the Revd Andrew Windross, vicar of St Peter's, De Beauvoir Town in Hackney, who has let them into the church crypt where they spend the night on mattresses on the floor. Even in the present fine weather it is surprisingly cold there. There are no proper facilities for washing, let alone bathing. Early in the morning they fold up their blankets and move off in columns to the Kurdish Work- ers' Association where they get something to eat before they spend the day wandering aimlessly around Hackney.

These are some of the 700 to 800 Kurds who have turned up at Heathrow Airport in the past few weeks and have been passed on 'into the care of the community', as a Home Office spokesman put it to me. What has really happened is that the immigration authorities, faced with a situa- tion for which I can think of no parallels in modern British history, have been simply unable to keep from 15 to 100 people a day claiming political asylum in their detention centres and have just shuffled them out of the door in the hope that somebody else will look after them while the powers-that- be make up their minds what to do.

Another group of Kurds are to be found camped in the United Reformed Church in Rectory Road, also in Hackney. Outside I greeted one man and, using international sign language, I was able to learn that he was a farmer or building worker (vigorous digging movements), married with three children (he patted them on their imagin- ary heads) and liked football. Inside I was able to make greater progress with an Interpreter. One said that he knew little of England except that Mrs Thatcher (whose name he pronounced with a most marvel- lous gutteral emphasis) was the President; 1 hoped that this would go down well at his Home Office interview. While we were talking, a doctor was brought in by the church workers and examined some of the 20 people there. Many had ear, chest or foot infections and one, in particular, was greeted with dismay; to be hospitalised in a very strange country with no hope of being able to make yourself understood is a frightening prospect.

What, I asked them, had they left behind? Many of them have wives and children, houses and work, so clearly the impulse to up and leave had been strongly felt. They all had stories to tell about what they saw as growing tension between ethnic Turks and Kurds at home and some said that they had bribed their way to getting passports so they could leave at once. They said that they lived in a military zone under the direct rule of a govenor; in their region, Maras, right-wingers had come to power in recent local elections and they feared a renewal of hostilities towards the indigenous Kurds, like the massacre of

117 Kurds in Eastern Turkey reported ten Years ago. Once at Heathrow they had all

been kept for some hours in a waiting room, then interviewed and released to the addresses of such organisations as the KWA. They will be asked back again for more interviews later. So far it seems that a few who came before the present flood have been granted 'exceptional leave' to stay although others face the threat of deportation.

Running out of money, tired and frus- trated as they were, these Kurds were much as 19th-century travellers had written of them when they visited this traditionally tribal and semi-nomadic people — proud but friendly. Once they had a fierce reputa- tion for great lawlessness when excited by their dervishes. As part of his secularisa- tion programme, Ataturk came down heavily on a rebellion in his Kurdish provinces in 1925. When the British were in Iraq our government was committed to at least some degree of self-rule for the Kurds but, as has happened throughout most of their history (they go back at least as far as the Assyrian Empire where they were known as the Gardu or Kardu; Strabo refers to them as the Kardakes) they ended up pushed to one side. The only native Kurd whom most of us are likely to have heard of is Saladin, the first Ayyubite Sultan of Egypt and scourge of the Crusad- ers.

In recent times they have suffered terr- ibly as a result of the Iran-Iraq war. Turkey, as well as Iran and Iraq fears a rise in Kurdish national consciousness (there are also Kurdish populations in Syria and the Soviet Union). Their language, which belongs to the Persian group, is proscribed in Turkey and there are fears that the Turkish government has set in hand a policy of resettlement in order to break up their concentrations of population.

But pressures from the Turkish govern- ment, which adamantly refuses to class these people as anything other than 'Turks', are only one source of the present problems facing the men sleeping in the crypts and churches of east London. They are stuck in the middle of a disagreement between our Home and Foreign Offices; the former murmurs darkly about 'a long- standing review' of whether or not visas should be required for those travelling to the United Kingdom from Turkey, while the Foreign Office is anxious not to offend a Nato ally, which cherishes a hope of one day becoming a member of the European Community.

The Turkish government says that these people have come to Britain for economic reasons, even though I got the strong impression from talking to them that the Turkish government is not exactly trying to stop them from leaving. The Home Office official I spoke to seemed to suggest this line as well by carefully reading out a list of the valid reasons for which people can succeed in being granted political asylum; and then pointing out that economic reasons did not figure on it. Our Home Office began by falling in with the Turkish approach and calling them 'Turks'. They insisted that they would be taken care of by the 'Turkish community'. In fact the brunt of the work of looking after these destitute people has fallen on the Kurdish Workers' Association whose members feel at odds with many of the Turkish organisations in this country.

But the central problem here is really of the Government's own making. As Ihsan Qadir of the KWA put it to me, 'Britain has opened its doors to them but has not clarified its view on whether they are refugees or not.' It is in everyone's in- terests that the Government looks into their case and their claims with expedition. At the moment nobody could doubt that the Kurds of Hackney present the pathetic appearance and condition of classic re- fugees; but more than this, they are suffer- ing from the great curse of refugees down the ages — nobody in authority is prepared to take responsibility for them. Only the churches have been prepared to act in extremis with no prior notice; and their manpower and financial resources are being stretched almost to breaking-point.

'Trevor, this is Peter. He's got a hump too.'

Previous page

Previous page