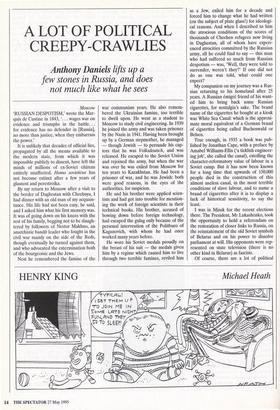

A LOT OF POLITICAL CREEPY-CRAWLIES

Anthony Daniels lifts up a

few stones in Russia, and does not much like what he sees

Moscow `RUSSIAN DESPOTISM,' wrote the Mar- quis de Custine in 1843, `. . . wages war on evidence and triumphs in the battle. . . for evidence has no defender in [Russia], no more than justice, when they embarrass the power.'

It is unlikely that decades of official lies, propagated by all the means available to the modern state, from which it was impossible publicly to dissent, have left the minds of millions of ex-Soviet citizens entirely unaffected. Homo sovieticus has not become extinct after a few years of glasnost and perestroika.

By my return to Moscow after a visit to the border of Daghestan with Chechnya, I had dinner with an old man of my acquain- tance. His life had not been easy, he said, and I asked him what his first memory was. It was of going down on his knees with the rest of his family, begging not to be slaugh- tered by followers of Nestor Makhno, an anarchistic bandit leader who fought in the civil war mainly on the side of the Reds, though eventually he turned against them, and who advocated the extermination both of the bourgeoisie and the Jews.

Next he remembered the famine of the war communism years. He also remem- bered the Ukrainian famine, too terrible to dwell upon. He went as a student to Moscow to study civil engineering. In 1939 he joined the army and was taken prisoner by the Nazis in 1941. Having been brought up by a German stepmother, he managed — though Jewish — to persuade his cap- tors that he was Volksdeutsch, and was released. He escaped to the Soviet Union and rejoined the army, but when the war was over he was exiled from Moscow for ten years to Kazakhstan. He had been a prisoner of war, and he was Jewish: both were good reasons, in the eyes of the authorities, for suspicion.

He and his brother were applied scien- tists and had got into trouble for mention- ing the work of foreign scientists in their technical books. His brother, accused of bowing down before foreign technology, had escaped the gulag only because of the personal intervention of the Politburo of Kaganovich, with whom he had once worked many years before.

He wore his Soviet medals proudly on the breast of his suit — the medals given him by a regime which caused him to live through two terrible famines, reviled him as a Jew, exiled him for a decade and forced him to change what he had written (on the subject of plate glass!) for ideologi- cal reasons. And when I described to him the atrocious conditions of the scores of thousands of Chechen refugees now living in Daghestan, all of whom have experi- enced atrocities committed by the Russian army, all he could find to say — this man who had suffered so much from Russian despotism — was, 'Well, they were told to surrender, weren't they?' If one did not do as one was told, what could one expect?

My companion on my journey was a Rus- sian returning to his homeland after 25 years. A Russian émigré friend of his want- ed him to bring back some Russian cigarettes, for nostalgia's sake. The brand name of the cigarettes he bought at a kiosk was White Sea Canal: which is the approxi- mate moral equivalent of a German brand of cigarettes being called Buchenwald or Belsen.

True enough, in 1935 a book was pub- lished by Jonathan Cape, with a preface by Amabel Williams-Ellis Ca ticklish engineer- ing job', she called the canal), extolling the character-reformatory value of labour in a Soviet camp. But it has now been known for a long time that upwards of 150,000 people died in the construction of this almost useless canal, in the most terrible conditions of slave labour, and to name a brand of cigarettes after it is to display a lack of historical sensitivity, to say the least.

I was in Minsk for the recent elections there. The President, Mr Lukashenko, took the opportunity to hold a referendum on the restoration of closer links to Russia, on the reinstatement of the old Soviet symbols of Belarus and on his power to dissolve parliament at will. His opponents were rep- resented on state television (there is no other kind in Belarus) as fascists.

Of course, there are a lot of political creepy-crawlies in the former Soviet Union. On Victory Day, for example, a newspaper which claimed a circulation of 100,000 published an article complaining that the celebrations of the 50th anniver- sary of the defeat of the Germans had been perverted by a Zionist plot. The proof of this was that the medal issued for the occasion showed three stars over the Kremlin — and they were in the shape of Stars of David. Each such star has six points, and since there were three of them, they clearly were intended to represent the mark of the beast, 666. Another article suggested that the work of extermination had not been complet- ed, but might be one day.

Nevertheless, for Mr Lukashenko and his communist supporters to represent his opponents as fascists and by implication supporters of mass murder was really a bit rich. For the communists themselves had been no slouches when it came to mass murder in Minsk: one of the suburbs of the city was built on a mass grave of between 100,000 and 250,000 'enemies of the peo- ple' shot from 1937 to 1941. This inconve- nient fact was passed over in complete silence.

Everywhere we found people sighing for the days of Brezhnev. It had been a golden age, when the world seemed unchanging and the nomenklatura did not have BMWs with which to inflame popular resentment. Decades of communism taught that a quiet life and a more or less regular food supply were the most that could be expected of life: all other ends were illusory. Quixotic gestures in favour of freedom or against injustice resulted in terrible hardship. It was a lesson well and thoroughly learnt; and one cannot help but wonder whether this fact will prove in the long run more significant than any number of the surface political changes so assiduously recorded by commentators.

Previous page

Previous page