Ulster

Girding the loins

Joseph McSimon

A much overlooked technique in politics is the Japanese art of belly-talk. This is the trick of making a statement for general consumption which contains a far different real message for a specific audience. It is not known if Mr Tanaka gave Mr Whitelaw any pointers on belly-talk during their nine holes of golf in a roaring gale. But the Government's policy towards Ulster over the past two weeks has been a classically successful example of it.

For Mr Heath's much-criticised 'integration' comments following the Dublin summit were no exercises. in petulance or kite-blowing. Amind the flurry of indignant statements and awkward denials over the following day's two significant things happened. Firstly, Mr Gerry Fitt and his Social and Democratic Labour Party lost their coyness about having talks with the Alliance Party and Mr Faulkner's Unionists about forming a new Executive. They got the real message — that the British Prime Minister, after having ample opportunity to sound out the Taoiseach, felt free to threaten publicly a policy of integration. The unpleasant shock that a Dublin government, under British pressure, could even contemplate such a message drove Mr Fitt to the conference table.

But Mr Cosgrave's co-operation was not forthcoming without a quid pro quo. What this was becomes clear from a second fact. After the Dublin summit Eire Minister of Foreign Affairs, Dr Garret Fitzgerald,no doubt in full knowledge of his government's understanding of the British position, told a New York audience that "the Council of Ireland would hold out to the majority of the Irish people a prospect of progress toward the unity that is their legitimate aspiration." The Council of Ireland has been sold to the Protestants of the North as an icing on the Executive cake. The Assembly Executive is to have equal representation on the Council with the government of the Republic. But in any

Unionist-SDLP coalition the SDLP representatives on the Council would assure a built-in Republican majority. Fianna Fail, Fine Gael and the Irish Labour Party are none of them suspected of actually favouring partition.

Below the belly-talk the real message of the Constitution Act to Dublin is that provision is made for consultation by the Northern Executive (appointed by Mr Whitelaw in his George III role and not by the Assembly) with any authority in the Republic. The Dublin government is, significantly, not excluded. The Act puts no restrictions on what may be discussed. Indeed, it emphasises the fact. Therefore both security and the border are topics potentially subject to interference by the Republic on the Council of Ireland.

In such circumstances, for Mr Faulkner to agree to parity with the SDLP on the Executive, with Alliance holding the balance and Without any guarantees tooffset the potential threat inherent in the Constitution Act — would be political suicide. As matters stand the Paisley-Craig coalition commands equal strength to him in the Assembly. And not only must he face this, but many of his own assemblymen have made it quite clear they would not stand for a "sell-out" to the SDLP.

Hence Mr Faulkner's insistence on four Main principles before appointments to the Executive: firm commitments to (1) the Constitution Act, (2) the security forces, (3) the principle of collective responsibility, and (4) the forswearance of violent and undemocratic methods.

One might assume that these conditions, especially (1) and (4), would be the foundation

of any democratic system. But the Assembly Executive is not a democratically elected government. It is a reversion to the Kaiser's Reichstag or the eighteenth century House of Commons, with Mr Whitelaw on the throne. The parallel is not reassuring. We know what happened to the Kaiser in 1918 and George HI lost America. The Assembly Executive cannot be democratic. For if it was, the clearly expressed wish of the Protestant majority — reflected by the Paisley-Craig block and many of the Official Unionists — would have to be realised. This is for no compromise what,soever with the SDLP; in short, for "No Surrender." Such, a policy, implying repres sion, is anathema to Westminster, and is anyway politically impossible in the present Climate of British opinion. Hence the British Fommitment to making the Assembly work — In spite of the people of Ulster.

It will fail. Mr Faulkner must lay down his four principles and the demand for a Unionist Majority on the Executive as his minimum demands for political survival. Similarly, Mr Fitt cannot accept these conditions, for they

Would effectively foreclose the United Ireland 0Ption his followers are determined on. So COmpromise must fail leaving the British ullimately, in their own eyes, only with the Option of withdrawal.

Both sides in Ulster are girding for that day. It has often been argued that the failure of the I-JOA and Sinn Fein in the Assembly elections Proved the desire of the people for jaw, jaw rather than war, war. In fact it only showed the people felt that the problems for jaw, jaw

and war, war needed different experts. Accordingly, while the politicians dance their

doomed quadrille, the hard men are preparing. The Army has, tor the moment, knocked the Provisionals out of the ring. Depleted battalions of raw teenagers struggle to keep the flame alive. But the eclipse of the Provisionals has cleared the way for a reemergence of the Officials, in the shadows

since the conservative Fianna Fail government breathed life into the Provos in winter 1969/70. The shooting of Provo leader Jim

Bryson may well have been Official work. Unlike the nationalist Provos, the Marxist

Officials do not want to fight a strictly sectarian war. Further, they look to Russia rather

than China tor ttriance, arms, and training. Accordingly, they lay less stress on general terror and more on discriminating attacks on the system. Thus their campaign will not be indiscriminate terror bombing, but attacks on security forces and government personnel.

The England bombings by the Provos will continue sporadically. They are currently a more viable outlet than attacks in Ulster and pay far higher political dividends. In London, unlike Belfast, terrorism is still unusual.

Meanwhile the Protestant extremists make the running. At least 25 explosions, many large, are ascribed to them in September by police. Catholic churches and pubs are favourite targets. Warnings are not always given and are usually brief. Still, so far the aim seems to have been to destroy property rather than people. It may not stay that way. The escalation of the Provo bombing campaign two and a half years ago was remarkably similar.

For all its increasing scale Protestant violence is still only the work of a militant fringe. The real Protestant backlash has yet to he heard from. Thus the shipyards, for example, have so far been relatively free of serious sectarian violence, despite the rise of Billy Hull's Loyalist Association of Workers after the introduction of direct rule. But this is not to say that Protestant tempers are not running short. The UDA, through which mass

Protestant militancy in Belfast is expressed, has taken a turn to the right with the eclipse and then murder of its vice-chairman Tommy Heron. Heron had stood and been beaten as a UDA candidate in the Assembly elections. He represented those who would have made the UDA a political movement. He also — it is said — benefited from a flourishing protection racket. His eclipse confirmed the USA as a militant, sectarian people's army.

The 5,000 strong "highly-trained" Protestant army recruited by the Deputy-Lieutenant of Co. Down is also the shape of things to come. Its unveiling no doubt came as a nasty surprise to British Army Intelligence which, for all its undoubted success in penetrating militant groups in Belfast, cannot enjoy such success in sparsely-populated country areas where everyone knows everyone else. Should the civil war long threatening the Province

finally break, the bloodiest and most important insurrections will be in those remote

rural areas. Thus the Protestant farmers have a long, militant tradition crowned by their defeat of the IRA in 1922 within the framework of the 'B' Special Constabulary. So far they have held back both from fringe Protestant extremism and the urban masses of the UDA, except with financial support.

Should they feel a sell-out was imminent, however, they would certainly enter the ring.

The rural Protestant potential for violence was briefly and luridly revealed at Burntollet Bridge in January, 1969. It has had four and a half years of terror and sectarian hatred to fester and organise since then. Should rural Protestant Ulster set up "no-go" areas over stretches of, say, Co. Antrim or assert itself on the Eire border it is debatable whether the Army, heavily stretched as it is, has the manpower to contain them. Under such conditions that tired old imperial ceremony, exercised in India, Palestine, and Aden, of withdrawal from chaos might well be revived.

Such contingencies still sound fanciful and alarmist in Britain where the dreadful implications of a withdrawal from Ulster are generally ignored. In Ulster itself they are recognised only too well. Thus the govern ment's tactical triumph in belly-talk in getting the Assembly talks going pales into insig nificance beside the grim realities of the conflict. The politicians continue to cry, "Peace, peace," when there is no peace. But the people are girding themselves for war.

'Joseph McSimon' is the pseudonym of a Belfast historian.

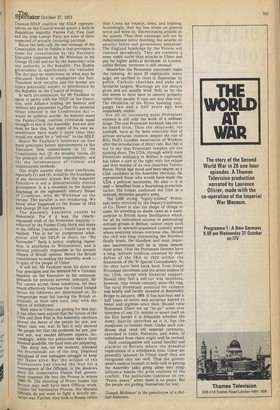

Previous page

Previous page