A moral necessity

Peter Mullen

Mrs Thatcher has called for the return of the death penalty. When she spoke on television about her ordeal in Brighton, she did not sound vengeful or angry, only calm and relieved to find herself still alive. But whenever the ordin- ary citizen or the Member of Parliament "Peaks in favour of the death penalty, he is invariably accused of blood-thirstiness and the desire to return to savagery. If a clergyman argues for capital punishment, as I have done recently, he is vilified as godless, merciless and unworthy of his Holy Orders.

So let me say immediately it is not vengeance which makes me vote for the death penalty. Though it should be pointed out that the doctrine 'An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth' was never meant as an incitement to macabre revenge; it is Intended to mean 'Only one eye for one eye — one tooth for one tooth.' It is a limitation on the scope of vengeance, not a licence to massacre.

However, many people feel let down by a so-called democratic tradition which allows a referendum on the Common Market but which will not permit one on this issue which engages everyone's feel-

gs• The man in the street — and the single or widowed woman living in a house by herself — senses that something has one wrong with the order of justice in the and when a murderer and multiple rapist is sentenced to 20 years in all as 'life' for his crimes. That would, in theory, grant him the freedom to resume his terrorism in his Middle age. And what of a case where a man has savagely assaulted and raped half a dozen women? There is a huge police Manhunt. But the rapist knows that, if he is cornered, he can commit murder in his attempt to escape — and there is no !Migher penalty to be suffered than what he has earned already. This is unjust. I do not know the answer to the argu- ment about deterrence though the rapid and great increase in the number of mur- ders since abolition must at least be allowed to count as evidence. If it is not, then surely nothing could ever count as evidence.

The only secure argument for the res- toration of the death penalty is that it is just. It is the proper penalty for murder. If someone takes life unlawfully, then his life must be taken by- the process of law itself. Most people see this as intuitively right. It is fitting.

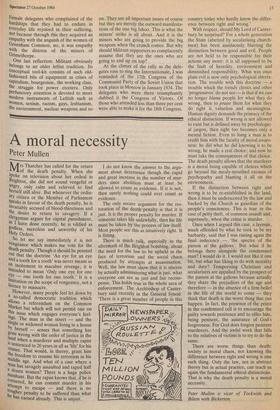

There is much talk, especially in the aftermath of the Brighton bombing, about the need for the law to be upheld in the face of terrorism and the social chaos produced by attempts at assassination. Well, the law must show that it is sincere by actually administering what is just, what everyone can see as just and fair recom- pense. This holds true in the whole area of enforcement. The Archbishop of Canter- bury said recently in the General Synod: 'There is a great number of people in this

country today who hardly know the differ- ence between right and wrong.'

With respect, should My Lord of Canter- bury be surprised? For a whole generation the State (abetted by secularising church- men) has been assiduously blurring the distinction between good and evil. People are not held to be responsible for their actions any more: it is all supposed to be the fault of heredity, environment and diminished responsibility. What was once plain evil is now only psychological aberra- tion. The trouble with this doctrine — a trouble which the trendy clerics and other 'progressives' do not see — is that if we can no longer blame people for what they do wrong, then to praise them for what they do right is valueless and meaningless. Human dignity demands the primacy of the ethical distinction. If wrong is not allowed to exist but is defined away by psychologic- al jargon, then right too becomes only a mental fiction. Even to hang a man is to credit him with the faculty of moral aware- ness: he did what he did knowing it to be wrong; he made a real choice; and now he must take the consequences of that choice. The death penalty allows that the murderer is a moral being capable of choices which go beyond the mealy-mouthed excuses of psychopathy and blaming it all on the environment.

If the distinction between right and wrong is to be re-established in the land, then it must be underscored by the law and backed by the Church as guardian of the people's consciences. This is true in the case of petty theft, of common assault and, supremely, when the crime is murder.

Once when I argued this case, a layman, much offended by what he took to be my barbarity, said that I was raising again the final indecency — 'the spectre of the parson at the gallows'. But what if he belongs there alongside the condemned man? I would do it. I would not like it one bit, but what has liking to do with morality and duty? Temporising Christians and secularisers are appalled by the prospect of the parson at the gallows because actually they share the prejudices of the age and therefore — in the absence of a firm belief in the life of the world to come — they think that death is the worst thing that can happen. In fact, the presence of the priest in the condemned cell is to encourage the guilty towards penitence and to offer him, being penitent, the assurance of God's forgiveness. For God does forgive penitent murderers. And the awful work that falls to the relatives of victims is to try to do the same.

There are worse things than death: society in moral chaos, not knowing the difference between right and wrong is one such thing. Only the law, not in abstract theory but in actual practice, can teach us again the fundamental ethical distinctions. That is why the death penalty is a moral necessity.

Peter Mullen is vicar of Tockwith and Bilton with Bickerton

Previous page

Previous page