THE GROCER AND THE BUTCHER

John Simpson reports on a game of unhappy families in Baghdad

Baghdad AL-JOMHORIYA couldn't quite bring itself to splash with the meeting on Mon- day morning, but there, just below the fold on the smudgy front page of the government-controlled Iraqi daily, were the familiar features: the curiously pointed nose, the silvery hair, the absence of neck. And facing him in the photograph were features which ten weeks of international crisis have rendered even more familiar: a bushy black moustache, a jowly outline, two pebble eyes. Saddam Hussein encoun- ters Edward Heath — 'one of the most respected Western statesmen to meet the President since the beginning of August', the accompanying article gushed. Apart form Kurt Waldheim of Austria, to whom the epithet 'respected' has been rarely applied in recent years, Bulent Ecevit from Turkey and the Vice-President of Bulgaria — who aren't strictly speaking Western and Jesse Jackson, who can scarcely be called a statesman at all, it is hard to think who else the writer could have been thinking of. Respected Western statesmen have not been much in evidence in Bagh- dad during the Gulf crisis, for the simple reason that most of them don't think Saddam Hussein has a point of view that is worth hearing; and even if they did, they probably wouldn't have the courage to come and listen to it.

Instead we have had any number of political tourists coming here. Some gen- uinely try to help. Others are attracted like bluebottles to a joint of meat, and, seeing some advantage to themselves, fly in to land on it. In the lobby of the Al-Rasheed hotel, a long echoing affair in white marble with crematorium glass in the windows, you can see them every day of the week: groups of shapeless Italians, Germans in cord jackets, a clutch of gawky Finns, uncomprehending Japanese, warring groups of peace campaigners who disagree about the rival merits of a peace camp as opposed to a peace trek. There is even a small nervous party of Iranian diplomats with stubbly chins and no ties, who hoped to go unnoticed, and I wished them `shobh bekhehr'. Most of these people came here to plead for the release of their fellow countrymen, but few got anywhere near the presidential palace; Saddam Hussein's advisers are too canny for that. Neverthe- less anyone who can give the President added status can expect to meet him: even an impressively moustachioed lady MP from Spain, who led a party of luminaries from the Madrid Left to the palace. Each of them bowed over the presidential hand at the moment of meeting, and Saddam smiled, obviously gratified: normally only the locals do that sort of thing. Their reward was to be allowed to take all the Spanish prisoners home with them.

Edward Heath didn't bow. There wasn't even an inclination of the head, and the famous teeth, less white than before, were scarcely in evidence. There was nothing of friendliness in his approach, just courtesy. He and Saddam sat for three hours in two white leather chairs, with the patterns of everything clashing, the Iraqi flag between them and the curtains drawn against the noonday sun. There were only three others in the room: Mr Tariq Aziz and two translators. In spite of the fact that Mr Heath was 74 and had no one to take notes for him, his powers of recall were such that he was able to give a highly detailed report of what he said when he met his own people and the British ambassador after- wards.

There had never been any doubt that Saddam Hussein would agree to Mr Heath's taking with him the elderly and sick prisoners when he left. There are plenty of others to act as human shields around Saddam's military and economic installations. It seemed possible that the Iraqis were actually collecting old and sick people in order to have some reward for politicians of stature who made the journey to Baghdad. The battle came over how many relatively young and healthy prison- ers Mr Heath could take with him; and there was a distasteful amount of haggling to be done between Mr Heath's assistants and the Iraqis before a final figure was agreed upon. It was characteristic of a system that holds ordinary people hostage, while calling them 'guests' and 'heroes of peace', that even the most seriously ill should have been kept in ignorance of their coming freedom.

If Mr Heath's purpose had been purely humanitarian, he might have received less criticism at home for coming here. But his political involvement preceded his altru- ism. He believed Mrs Thatcher's approach and style were all wrong in the Gulf crisis, and said so. His trip to Baghdad was the logical conclusion of his speech to the especially recalled House of Commons; the approach to him by the relatives of the prisoners — reinforced, he says, by the Foreign Office — offered him a good reason to give the most practical shape to his opposition. By coming to Baghdad he was doing what he blamed Mrs Thatcher for refusing to do: he was negotiating with Saddam Hussein rather than joining in the general confrontation. 'I don't quite frank- ly believe that enough is being done on the diplomatic front,' as he said at his press conference.

The problem about negotiating with Saddam's Iraq is that its notion of diplom- acy usually consists of taking as extreme a position as it can and challenging everyone else to accept it. When Saddam told Mr Heath he wished to do everything possible through diplomatic means to achieve a peaceful solution to the crisis, he meant that he wanted the countries which had sent troops to Saudi Arabia to come to terms with the idea that Iraq now owned Kuwait, and to take their troops home again.

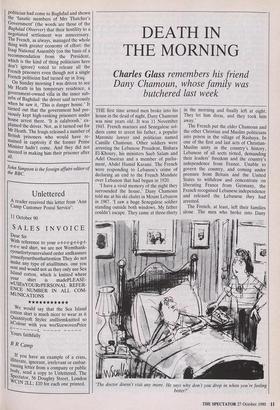

On the other hand, Mr Heath managed to get the President to repeat to him the phrase that so heartened the Soviet envoy, Yevgeniy Primakov, when he met Saddam two weeks ago. The phrase was 'Iraq remains flexible' and Mr Primakov inter- preted that as meaning that Iraq was preparing to wrong-foot the West by with- drawing to its old boundaries, a third of the way up the length of Kuwait. When I suggested such a thing, in a television broadcast, the Baghdad Observer devoted an entire editorial to the evil habits of Western correspondents who 'simulate the patterns of truth in order to deceive the unwary'; but everyone here knows that however much the official media swear that Kuwait belongs to Iraq in perpetuity, if Saddam Hussein were to announce a decision to relinquish two thirds of its newly annexed territory, the same media would praise his statesmanship. Mr Prima- kov was right to get excited when Saddam spoke about flexibility, and Mr Heath did well to get him to repeat the phrase. That alone would not be enough to justify Mr Heath's essay in international peace-making. The release of the British hostages was its own reward and well worth the journey. But Mr Heath's critics were wrong about one thing: there was no sudden upsurge in Iraqi propaganda as a result of his visit. The line which was taken here was merely that one sensible British politician had come to Baghdad and shown the 'fanatic members of Mrs Thatcher's Government' (the words are those of the Baghdad Observer) that their hostility to a negotiated settlement was unnecessary. The French, as always, managed the whole thing with greater economy of effort: the Iraqi National Assembly (on the basis of a recommendation from the President, which is the kind of thing politicians here don't ignore) voted to release all the French prisoners even though not a single French politician had turned up in Iraq. On Sunday morning I was driven to see Mr Heath in his temporary residence, a government-owned villa in the inner sub- urbs of Baghdad: the driver said nervously when he saw it, 'This is danger house.' It turned out that the government had pre- viously kept high-ranking prisoners under house arrest there. 'It is calaboosh,' ex- plained the driver. Not, as it turned out for Mr Heath. The Iraqis released a number of British prisoners who would have re- mained in captivity if the former Prime Minister hadn't come. And they did not succeed in making him their prisoner after all.

John Simpson is the foreign affairs editor of the BBC.

Previous page

Previous page