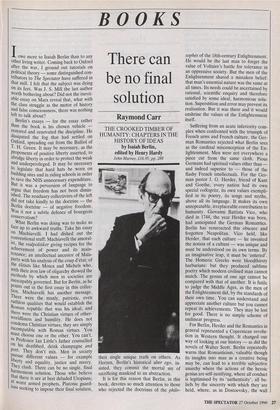

BOOKS

There can be no final solution

Raymond Carr

THE CROOKED TIMBER OF HUMANITY: CHAPTERS IN THE HISTORY OF IDEAS by Isaiah Berlin, edited by Henry Hardy

John Murray, £16.95, pp. 288

Iowe more to Isaiah Berlin than to any other living writer. Coming back to Oxford after the war, I ground out tutorials on political theory — some distinguished con- tributors to The Spectator have suffered in that mill. I felt that the subject was dying on its feet. Was J. S. Mill the last author worth bothering about? Did not the inevit- able essay on Marx reveal that, what with the class struggle as the motor of history and false consciousness, there was nothing left to talk about?

Berlin's essays — for the essay rather than the book is his chosen vehicle restored and renovated the discipline. He dissipated the fog that had settled on Oxford, spreading out from the Balliol of T. H. Green. It may be necessary, as the proponents of positive liberty asserted, to abridge liberty in order to protect the weak and underprivileged. It may be necessary to legislate that hard hats be worn on building sites and in riding schools in order to save the NHS unnecessary expenditure. But it was a perversion of language to argue that freedom has not been dimin- ished. The residuary collectivists of the left did not take kindly to the doctrine — the Berlin doctrine — of negative freedom. Was it not a subtle defence of bourgeois conservatism?

What Berlin was doing was to make us face up to awkward truths. Take his essay on Machiavelli. I had dished out the conventional stuff: Machiavelli the amoral- 1st, the realpolitiker giving recipes for the achievement of power and its main- tenance; an intellectual ancestor of Mala- pane with his analysis of the coup d'etat; of the elitists like Mosca and Michels who, with their iron law of oligarchy showed the methods by which men in societies are inescapably governed. But for Berlin, as he points out in the first essay in this collec- tion, Machiavelli has another message. There were the manly, patriotic, even ruthless qualities that would establish the Roman republic that was his ideal; and there were the Christian virtues of other- worldliness and humility. He does not condemn Christian virtues; they are simply incompatible with Roman virtues. You must choose one or the other. You can't, as Professor Ian Little's father counselled on his deathbed, drink champagne and port. They don't mix. Men in society pursue different values — for example liberty and equality, justice and mercy. They clash. There can be no single, final harmonious solution. Those who believe that there is are at best deluded Utopians; at worst armed prophets, Platonic guard- ians seeking to impose their final solution, their single unique truth on others. As Herzen, Berlin's historical alter ego, in- sisted, they commit the mortal sin of sacrificing mankind to an abstraction.

It is for this reason that Berlin, in this book, devotes so much attention to those who rejected the doctrines of the philo- sophes of the 18th-century Enlightenment. He would be the last man to forget the value of Voltaire's battle for tolerance in an oppressive society. But the men of the Enlightenment shared a mistaken belief: that man's essential nature was the same at all times. Its needs could be ascertained by rational, scientific enquiry and therefore satisfied by some ideal, harmonious solu- tion. Superstition and error may prevent its realisation. But it was there and it would enshrine the values of the Enlightenment itself.

Suffering from an acute inferiority com- plex when confronted with the triumph of French arms and French culture, the Ger- man Romantics rejected what Berlin sees as the cardinal misconception of the En- lightenment. Men were not everywhere a piece cut from the same cloth. Pious Germans had spiritual values other than and indeed superior to — those of the flashy French intellectuals. For the Ger- man pastor J. G. Herder, friend of Kant and Goethe, every nation had its own special volksgeist, its own values exempli- fied in its poetry, its songs , and myths, above all its language. It makes its own unrepeatable, irreplaceable contribution to humanity. Giovanni Battista Vico, who died in 1744, the year Herder was born, had anticipated the German Romantics. Berlin has resurrected this obscure and forgotten Neapolitan. Vico held, like Herder, that each culture — he invented the notion of a culture — was unique and must be understood on its own terms. By an imaginative leap, it must be 'entered'. The Homeric Greeks were bloodthirsty barbarians: but they produced sublime poetry which modern civilised man cannot match. The genius of one age cannot be compared with that of another. It is futile to judge the Middle Ages, as the men of the Enlightenment did, by the standards of their own time. You can understand and appreciate another culture but you cannot repeat its achievements. They may be lost for good. There is no simple scheme of unilinear progress.

For Berlin, Herder and the Romantics in general represented a Copernican revolu- tion in Western thought. It changed our way of looking at our history — as did the novels of Walter Scott. Berlin repeatedly warns that Romanticism, valuable though its insights into man as a creative being may be, can lead to a terrible subjective anarchy where the actions of the heroic genius are self-justifying, where all conduct is legitimised by its 'authenticity', all be- liefs by the sincerity with which they are held, where, as in Dostoevsky, the wall between the criminal and the good citizen is paper thin.

It may seem strange that so committed a liberal as Berlin should devote a long essay in this book to Joseph de Maistre, the Savoyard diplomat, whose denunciations of the French in the early years of the 19th-century Revolution titillated the Salons of St Petersburg. But Berlin has always been fascinated by those who swim against the tide of their times. De Maistre derived from his bleak Augustinian theolo- gy that man was irredeemably sinful, at the same time feeble-minded and a brutal killer of his fellow men. As a sinner, he can only be saved by grace in the next world and in this world from his destructive passions by the executioner who is the true saviour of society. But de Maistre saw something more terrible than those bone- headed Catholic reactionaries who be- lieved that European society in dissolution could only be saved by what Herzen called religion rechauffe. Like other Romantics, this writer of classical prose felt that society rested on mysterious dark forces, rather like the Japanese who believed that their country rested on the back of an angry dragon. Men's rational constructs — above all Liberal constitutions — must fail. It is the irrational, traditional institutions that will survive. Except that they scorned traditional institutions, Berlin believes the Fascists revived this cult of the dark forces with terrible results in our own times.

As every page of this book reveals, Berlin is a pluralist. Men pursue different ideals, they hold different values. And they clash. What is to be done? Berlin's answer is the trade-off. So much liberty for so much equality and so on. It is, as he recognises, neither an easy adjustment to make in practice nor a particularly inspir- ing battle cry. But it is the only rule by which civilised man can live.

Berlin deserted the analytic philosophy that dominated Oxford when he returned to teach after the war. The word games played by its practitioners, we suspected, were neither interesting nor important.

The guru of linguistic philosophy was the austere John Austin. Austin had drawn up Eisenhower's battle orders. Responsible for university discipline, he drew up an elaborate plan to deal with the Town and Gown Riots that used to erupt in Oxford on Guy Fawkes night. As his Proctor I had to implement these plans on the street. They were a disaster. I was knocked down and set on fire by a boy I had taught at Wellington. Austin had not, to use Vico's phrase, 'entered' the minds of the average undergraduate or Cowley worker. Berlin's supreme gift is his capacity to 'enter' the minds of the thinkers who have ushered in the great sea-changes of the Western mind.

Almost alone in the early days, he restored the history of ideas to its true place as a key to unlock the past and explain the present. It was a notable achievement. This book sustains it.

Previous page

Previous page