FINE ARTS SPECIAL

Heritage

The Miss Havisham suite

Ruth Guilding looks at the marketing of an English country house In 1979 the V & A mounted an exhibi- tion entitled The Destruction of the Coun- try House. The catalogue listed more than a thousand stately piles of architectural merit which had been abandoned or des- troyed during the previous 70 years. Since then, with the nativity of that behemoth the heritage industry, the tide has turned a little. Such buildings have once again become symbolic of a desirable, though almost completely obsolete lifestyle: Cliveden and Hartwell House have been refurbished as 'country house hotels'; Ked- leston and Calke Abbey have been saved thanks to the National Trust's massive publicity campaigns, and sales at ThoresbY Hall and Great Tew, skilfully marketed by the auction houses, attracted even more day-trippers than serious bidders. Today the National Trust can boast more members that it knows what to do with. Each summer, thousands of visitors shuffle through its properties, observing the carvings attributed to Grinling Gibbons and the ninth earl's penchant for taxidermy before enjoying much welcomed tea, nice clean toilets and a browse in the shop. The Trust, an independent charitable body which has been opening great houses to the Public since the 1930s, has developed its (win strong style and enjoyed uncritical admiration. More recently, however, the English country house look' imposed on so many of its properties — pastel shades from the palette of John Fowler and the ubiquitous pot-pourri bowls — has been _decried. Many column inches have also been given to the squabbles of those arbiters of taste responsible for the restora- tions at the Queen's House, Greenwich and the new Courtauld Galleries. In short, the mechanics of preservation and the application of taste are no longer the Private domain of the connoisseur-curator.

The stately homes of England How beautiful they stand, To prove the upper classes Have still the upper hand... .

As I arrived at Brodsworth Hall in York- shire, I recalled the words of Noel Co- ward's famous ditty. If Coward were alive today, he might add a verse about English Heritage, Lord Montagu's quango which has saved Brodsworth for the nation. English Heritage was formed in 1985 to take over some of the functions of the old Department of the Environment and to administer the historic sites and buildings formerly in the DoE's care — mainly abbeys, castles and sites like Stonehenge. In the preserve of country houses, howev- er, it has been overshadowed by the maturer identity of the National Trust.

A robust Classical revival house of the 1860s, Brodsworth stands within over- grown formal gardens and parkland. Like Calke Abbey in Derbyshire it has been dubbed a lime-capsule'. Its builder, Charles Sabine Thelluson, left it in turn to each of his three sons who all died without issue, and the house then passed via a cousin to the most recent owner, who gave the property to English Heritage in 1989. The Thellusons were solid and convention- al, interested in yachting and the turf, and their cousins were poor — consequently, the house's 19th-century interiors have survived with few alterations.

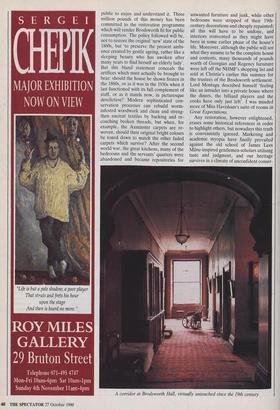

While English Heritage received the house as a gift, the contents have been purchased by the National Heritage Memorial Fund for £3.6 million. Brods- worth's importance centres on the com- pleteness of its interiors, which include handsome mahogany furniture and original soft furnishings, and a fair-to-middling collection of Italian sculpture rendered more imposing by the mirrored, marbled and tiled vistas within which it is viewed. `Rows and rows and rows of Gains- boroughs and Lawrences' there are not, but there is one rather fine Lawrence in the dining-room, and plenty of sporting prints. I arrived at the house before the first wave of builders, conservators and consultants had taken control, but the labours of cataloguers, labellers and photographers had already turned it into something closer to an archaeological site. Brodsworth is shabby, tatty and down-at-heel, and conse- quently conforms perfectly to the 'roman- tic dereliction' style now being marketed by the various homes-and-interiors maga- zines to a public which has become sated with the artifice of stipple, scumble and swag.

English Heritage receives money from the Government to perform its statutory duties — to preserve and conserve the historic environment and by means of education and presentation to enable the public to enjoy and understand it. Three million pounds of this money has been committed to the restoration programme which will render Brodsworth fit for public consumption. The policy followed will be, not to restore the original 'new' state of the 1860s, but 'to preserve the present ambi- ence created by gentle ageing, rather like a sleeping beauty who has awoken after many years to find herself an elderly lady'. But this bland statement conceals the artifices which must actually be brought to bear: should the house be shown frozen in the 1860s, or as it was in the 1930s when it last functioned with its full complement of staff, or as it stands now, in picturesque dereliction? Modern sophisticated con- servation processes can rebuild worm infested woodwork and clean and streng- then ancient textiles by backing and re- couching broken threads, but when, for example, the Axminster carpets are re- woven, should their original bright colours be toned down to match the other faded carpets which survive? After the second world war, the great kitchens, many of the bedrooms and the servants' quarters were abandoned and became repositories for unwanted furniture and junk, while other bedrooms were stripped of their 19th- century decorations and cheaply repainted; all this will have to be undone, and interiors reinvented as they might have been in some earlier phase of the house's life. Moreover, although the public will see what they assume to be the complete house and contents, many thousands of pounds worth of Georgian and Regency furniture were left off the NHMF's shopping list and sold at Christie's earlier this summer for the trustees of the Brodsworth settlement. Lord Montagu described himself 'feeling like an intruder into a private house where the diners, the billiard players and the cooks have only just left'. I was minded more of Miss Havisham's suite of rooms in Great Expectations.

Any restoration, however enlightened, erases some historical references in order to highlight others, but nowadays this truth is conveniently ignored. Marketing and academic myopia have finally prevailed against the old school of James Lees Milne-inspired gentlemen-scholars utilising taste and judgment, and our heritage survives in a climate of unconfident conser- A corridor at Brodsworth Hall, virtually untouched since the 19th century vatism. As a solid, handsome residence of the mid-Victorian squirearchy, Brods- worth is admirably matched to its new trustees, and if English Heritage can throw off its fear of public censure, it might take up the challenge to deal with this latest museum of country house life in a radical, non-anodyne way. Somehow, the ghastly progress of the heritage industry must be tempered, for although their rightful heirs have long ceased to live in most of them -

Previous page

Previous page