An English composer in Ireland

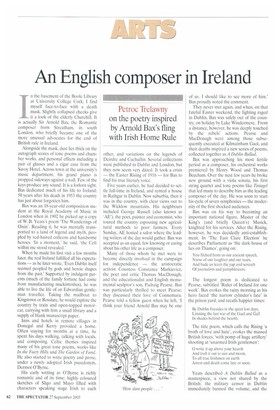

Petroc Trelawny on the poetry inspired by Arnold Box's fling with Irish Home Rule

In the basement of the Boole Library at University College Cork. I find myself face-to-face with a death mask. Slightly collapsed cheeks give it a look of the elderly Churchill. It is actually Sir Arnold Bax, the Romantic composer from Streatham, in south London, who briefly became one of the more unusual advocates for the end of British rule in Ireland.

Alongside the mask, dust lies thick on the autograph scores of tone poems and chamber works, and personal effects including a pair of glasses and a cigar case from the Savoy Hotel. Across town at the university's music department, his grand piano is propped sideways against a wall. Few of the keys produce any sound. It is a forlorn sight. Bax dedicated much of his life to Ireland; 50 years after his death in 1953 the country has just about forgotten him.

Bax was an 18-year-old composition student at the Royal Academy of Music in London when in 1902 he picked up a copy of W. B. Yeats's poem 'The Wanderings of Oisin'. Reading it, he was mentally transported to a land of legend and myth, peopled by red-haired colleens and handsome heroes. in a moment,' he said, 'the Celt within me stood revealed.'

When he made his first visit a few months later, the real Ireland fulfilled all his expectations — as he later wrote, 'Even Dublin itself seemed peopled by gods and heroic shapes from the past.' Supported by indulgent parents (much of the family fortune had come from manufacturing mackintoshes), he was able to live the life of an Edwardian gentleman traveller. Taking the mailboat to Kingstown or Rosslare, he would explore the country by train and open-topped motorcar, carrying with him a small library and a supply of blank manuscript paper.

Inns and hotels in remote villages in Donegal and Kerry provided a home. Often staying for months at a time, he spent his days walking, talking with locals, and composing. Celtic themes inspired many of his great tone poems, works like In the Faery Hills and The Garden of land. He also started to write poetry and prose, under a newly adopted Irish pseudonym. Dermot O'Byme.

His early writing as O'Byrne is richly romantic and of its time: highly coloured sketches of Sligo and Mayo filled with characters speaking stage Irish to each other, and variations on the legends of Deirdre and Cuchullin. Several collections were published in Dublin and London, but they now seem very dated. It took a crisis — the Easter Rising of 1916 — for Bax to find his true literary voice.

Five years earlier, he had decided to settle full-time in Ireland, and rented a house in Rathgar in Dublin. Now suburbia, then it was in the country, with clear views out to the Wicklow mountains. His neighbours included George Russell (also known as 'AE'), the poet, painter and economist, who toured the country espousing new agricultural methods to poor farmers. Every Sunday, AE hosted a salon where the leading writers of the day would gather. Bax was accepted as an equal, few knowing or caring about his other life as a composer.

Many of those whom he met were to become directly involved in the campaign for independence — the aristocratic activist Countess Constance Markievicz, the poet and critic Thomas MacDonagh, and the educationalist and English monumental sculptor's son. Padraig Pearse. Bax was particularly thrilled to meet Pearse; they discussed their love of Connemara. Pearse told a fellow guest when he left, 'I think your friend Arnold Box may be one

of us. I should like to see more of him.' Box proudly noted the comment.

They never met again, and when, on that fateful Easter weekend, the fighting raged in Dublin, Bax was safely out of the country, on holiday by Lake Windermere. From a distance, however, he was deeply touched by the rebels' actions. Pearse and MacDonagh were among those subsequently executed at Kilmainham Gaol, and their deaths inspired a new series of poems, collected together as A Dublin Ballad.

Box was approaching his most fertile period as a composer, his orchestral works premiered by Henry Wood and Thomas Beecham. Over the next few years he broke new ground with a viola sonata, his first string quartet and tone poems like Tintagel that led many to describe him as the leading composer of the day. He was soon to start his cycle of seven symphonies — the modernity of the first shocked audiences.

Bax was on his way to becoming an important national figure, Master of the King's (and briefly Queen's) Musick, knighted for his services. After the Rising, however, he was decidedly anti-establishment. In 'The East Clare Election' he describes Parliament as 'the dark house of lies on Thames', going on:

You filched from us our ancient speech. Nurse of our laughter and our tears, And bade us learn the yap and screech Of journalists and pamphleteers.

The longest poem is dedicated to Pearse, subtitled 'Ruler of Ireland for one week'. Bax evokes the rainy morning as his hero faced 'the narrow cylinder's fate' in the prison yard, and recalls happier times:

By Dublin firesides in the quiet lost days, Limning the last war of the Gael and Gall In shades behind the hearth.

The title poem, which calls the Rising 'a broth of love and hate', evokes the massed British forces. 'with pomp of huge artillery' shooting at 'unarmed Irish gentlemen': 0 write it up above your hearth And troll it out to sun and moon, To all true Irishmen on earth Arrest and death come late or soon.

Yeats described A Dublin Ballad as a masterpiece, a view not shared by the British: the military censor in Dublin immediately banned the volume, and the few hundred copies that had been printed quickly became prized possessions.

Bax had briefly found a cause that he believed in passionately, but, as Ireland fell into civil war, he soon became disillusioned. It was a decade before he started regularly visiting again, and, when he returned, it was not as an enthusiastic young would-be Gael, but as an important British composer, examining at universities and judging music competitions. He still travelled extensively — claiming he had been to all 32 counties — but much of the magic that had drawn him across the Irish Sea in the first place seemed to have gone.

In Britain, the 50th anniversary of his death on 3 October 1953 has prompted a revival of his music; the BBC Philharmonic has just recorded all his symphonies for CD release; the Queen heard November Woods, a tone poem by her once rather offmessage Master of Musick when she visited the Proms this season. But in the Irish Republic he is a neglected figure. None of his poetry is to be found in any current anthology, and the only work performed this autumn by the National Symphony Orchestra was his tone poem Tintagel, ironically a work inspired by Cornish legend.

In Cork — European City of Culture in 2005 — there is much talk of getting his piano working again and making the archive collection more accessible, but there seems little chance of raising the money to make anything actually happen. Bax was one of the greatest British symphonists of the last century, but his legacy has been blotted from the collective memory of the country he felt was his real home.

Previous page

Previous page