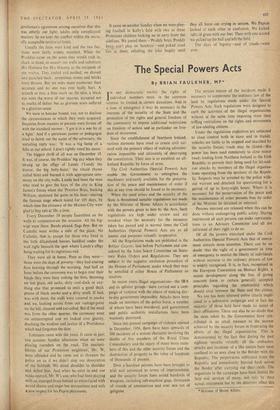

The Proddy Boys

By DESMOND FISHER

THE short cut to the Lone Moor Road was down the ramparts at the top of our avenue, through the barbed-wire defences of the enemy position and up-and-over the eight-foot-high wall of the fort he was holding. We were Tommies or Sioux or the French Foreign Legion as the spirit moved us; and we always used the short cut to school despite the thrashings we got for torn coats and muddied trousers.

Going to school was a daily adventure; for always—at the end of the journey, within a hundred yards of the school--we met the Proddy boys. and it was a disappointing morning that we didn't have a tight.

Procedure was strict and there was a code of honour to be observed. The first party on the scene—and we had to travel in a group for safety's sake—started in chalking the slogans on the walls. The side of the big warehouse was the best site, but the bigger thrill was to be had in writing on the walls or door of a private home. If we were there first we chalked up `To Hell with the King' and expressed another sentiment in His Majesty's regard of which few M us knew the meaning, but which was often used by our seniors and was considered derogatory enough for our purpose. Often it wasn't necessary to write a whole sentence: all we had to do was to cross out of rub out the word 'Pope' from similar senti- ments chalked up by some drunken Protestant the night before, and substitute the word 'King.'

Before very long those of our group detailed to 'keep nix' would give the warning and the Proddies would descend on us. There was always a momentary pause while we expertly estimated the size of the rival groups. If one group greatly outnumbered the other—and things like flu, exams, measles and mumps often upset the nor- mal balance—there would be an immediate swoop, a quick scuffle and the smaller faction took unceremoniously to their heels, and made for the nearest neutral area.

This was where the code of honour came in, Certain streets were accepted as no-man's-land; all the fighting had to take place there, In other streets, Papist and Proddy schoolboys could pass in peace. It was not that we felt any differently about one another but we had discovered that the adults in those streets did not hesitate to join in the fighting on one side or the other. Since some of the streets were 100 per cent Catholic and others exclusively Protestant, we had reached a gentleman's agreement among ourselves that this was strictly our fight; adults only complicated matters. So we kept the conflict within the mutu- ally acceptable territorial limits.

Usually the fates were kind and the two fac- tions were fairly evenly matched. When the Proddies came on the scene they would rush in. chalk in hand, to assault our walls and substitute His Holiness for His Majesty as the recipient of our wishes. They jostled and pushed; we shoved and punched back : sometimes stones and bricks were thrown. But we were more exuberant than accurate and no one was ever badly hurt. A scratch or two, a blue mark on the shin, a black eye were the worst of our injuries. accepted not as marks of defeat but as glorious scars suffered in a glorious cause We were in honour bound, too, not to disclose the circumstances in which they were acquired. Inquiries from masters or parents were frozen off with the standard answer: 'I got it in a wee bit of a fight.' And if a persistent parent or pedagogue tried to ferret out the name of the adversary, the unfailing reply was: 'It was a big lump of a fella at our school. I don't rightly mind his name.'

The biggest thrill of all was on December 18. It was, of course, the Proddies' big day when they strung up the effigy of Lundy ('Lundy the traitor, the big belly-bater.' the ribald rhyme called him) and burned it with appropriate cere- mony on the city, walls. Lundy had been the man who tried to give the keys of the city. to King James's forces when the 'Prentice Boys, backing William, slammed the gates in his face—starting the famous siege which lasted for 105 days, by which time the citizenry of the Maiden City were glad to buy rats at 10s. a time.

Every December 18 people assembled on the walls to commemorate the occasion. All the big- wigs were there. Bands played, flags flew. But no Catholic went within a mile of the place. No Catholic, that is, except for those who lived in the little dilapidated houses huddled under the wall right beneath the spot where Lundy's effigy hung waiting for its inglorious end.

They were all at home. Poor as they were— those were the days of poverty—they had roaring fires burning through the morning. And half an hour before the ceremony was to begin over their heads they.were busy stoking the fires, throwing on wet grass, old sacks, dirty coal-slack or any- thing else that promised to emit a good thick plume of black smoke and a dirty smell. If luck was with them, the wallS were covered in smoke and we, looking across from our vantage-point on the hill, cheered and cat-called. But if the wind was from the other quarter, the ceremony went on uninterrupted and we looked over glumly, doubting the wisdom and justice of a Providence which had forgotten the date.

Tolerance came with the years. It came in part one summer Sunday afternoon when we were playing rounders on the road. The suscepti- bilities of our Protestant neighbour, Mr. W, were offended and he came out to threaten the police on us if we didn't stop our desecration of the Sabbath. We stood shoulder to shoulder and defied him. And when he went in and our ranks opened, Mr. W's son, who had been playing with us, emerged from behind us white-faced with mixed shame and anger but unrepentant and with a new respect for his Papist playmates. It came on another Sunday when we were play- ing football in Kelly's field with two or three Protestant children looking on in envy from the sidelines. We jeered them—Proddy boys, Proddy boys, can't play on Sundays'—and poked cruel fun at them, relishing the joke hugely until they all burst out crying in unison. We Papists looked at each other in confusion. We kicked tufts of grass with our feet. Then with one accord we picked up the ball and left the field.

The days of bigotry—and of youth—were over.

Previous page

Previous page