The academics' seat

Ian Bradley

Oxford The rest of the world may still go on thinking of it in terms of scholarship, marmalade or bags, but for politicians and pundits, until after 3 May at least, Oxford is just a statistic — the 16th most marginal Labour seat in the country and one that the Tories must win if they are to form the next government.

Not that Oxford is any old marginal. The 1,036 votes that separated the two main parties at the last election must have included some rather intellectual ones. Where else would the Liberal candidate dare to quote Saint Augustine in his election address or have the pleasure of canvassing David Butler? And I doubt if the returning officer for Nelson and Colne is much troubled by complaints from the wives of peers that they have been left off the register along with their husbands.

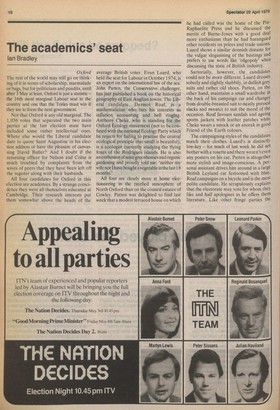

All four candidates for Oxford in this election are academics. By a strange coincidence they were all themselves educated at Cambridge. Their research interests put them somewhat above the heads of the average British voter. Evan Luard, who held the seat for Labour in October 1974, is an expert on the international law of the sea. John Patten, the Conservative challenger, has just published a book on the historical geography of East Anglian towns. The Liberal candidate, Dermot Roaf, is a mathematician who lists his interests as inflation accounting and bell ringing. Anthony Cheke, who is standing for the Oxford Ecology movement (not to be confused with the national Ecology Party which he rejects for failing to practise the central ecological principle that small is beautiful), is a zoologist currently studying the flying foxes of the Rodrigues islands. He is also an enthusiast of solar greenhouses and organic gardening and proudly told me: 'neither my wife nor! have bought a vegetable in the last 18 months.'

All four are clearly more at home electioneering in the rarefied atmosphere of North Oxford than on the council estates of Cowley. Patten was delighted to find last week that a modest terraced house on which he had called was the home of the PreRaphaelite Press and he discussed the merits of Burne-Jones with a good deal more enthusiasm than he had harangued other residents on prices and trade unions. Luard shows a similar donnish distaste for the vulgar sloganising of the hustings and prefers to use words like 'oligopoly' when discussing the state of British industry.

Sartorially, however, the candidates could not be more different. Luard dresses soberly and slightly shabbily, in dullish grey suits and rather old shoes. Patten, on the other hand, maintains a small wardrobe in the back of his campaign car and changes from double-breasted suit to neatly pressed slacks and sweater to suit the mood of the occasion. Roaf favours sandals and ageing sports jackets with leather patches while Cheke wears a smock or an anorak in good Friend of the Earth colours.

The campaigning styles of the candidates match their clothes. Luard's is distinctly low-key — tor much of last week he did not bother with a rosette and there weren't even any posters on his car. Patten is altogether more stylish and image-conscious. A personal assistant drives him around in a large British Leyland car festooned with blue. Roaf campaigns on a bicycle and is the most polite candidate. He scrupulously explains that the electorate may vote for whom they like and half apologises as he offers them literature. Like other fringe parties the Ecologists prefer producing large amounts of paper (recycled, one hopes) to door-todoor canvassing, although they are hoping to stage a bicycle rally this weekend. The siting of the main parties' headquarters nicely symbolises the two nations that make up the Oxford constituency. Labour directs its campaign from a shabby set of rooms behind the local headquarters of the TGWU down the Cowley Road. The Conservative offices are in the city centre and Within a few yards of the entrance to the Oxford Union. The Liberals operate from a series of houses in North Oxford, and the Ecology Movement headquarters are split between the University Zoology Building and the chalet in the middle of a wood Where their candidate lives.

Evan Luard maintains that it is, in fact, a Myth that Oxford is dominated by the University and Cowley. He points out that only around 6,000 of the 20,000 workers employed by British Leyland live in the city, and a smaller number are employed by the University. The majority of the population are engaged in light industry, and white collar jobs in commerce, education, health and local government. There is also a higher than average proportion of retired people. This may explain the less than total interest so far shown in the election by the car workers at Cowley. At one of the Conservatives' regular 6.am leafletting sessions outside the factory gates, Douglas Hurd was so Perturbed that none of the incoming or departing workers spoke to him that he concluded they must think he was a picket. Michael Heseltine had a similar experience When he went to speak in Cowley early last week. There were animated questions from the 30 or so people (average age 68) who came to hear him talk about the Tory policy on death grants, but none on the party's attitude to British Leyland. Heseltine was forced to ask himself a question on the subject so that he could assure the pensioners that the Conservatives had no intention of closing down Leyland or starving it of funds as the Socialists suggested.

The University seems hardly more interested in the election than the car workers. Denis Healey was met with a polite but rather bored reception when he addressed an audience which seemed largely cornPosed of dons and students in the Northgate Hall. If Hese'tine's problem was the age of 111s audience, Healey's was its youth. He felt n wise to remind them what life was like in 1974, clearly doubting that many of them Were of an age then to appreciate it. The citizens of Oxford, town and gown, have as yet shown a polite but firm lack of interest in the election in which they will play so crucial a part. They distinguish themselves from the rest of the British electorate, Perhaps, principally in the style with which they remove the politicians from their doorsteps. The best excuse I heard came from a woman who told the Tory candidate that She didn't have time to talk to him because she was in the middle of writing an article about the election in Turkish.

Previous page

Previous page