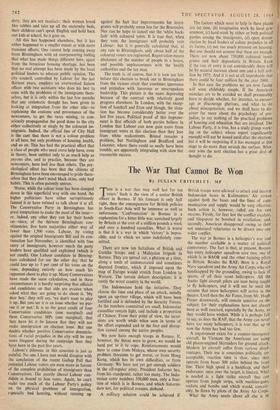

The War That Cannot Be Won

By JULIAN CRITCHLEY, MP

HIS is a war that may well last for ten

I years.' Such is the view of a senior British officer in Borneo. If his forecast is only half right, then the consequences for British policies in South-East Asia will be immense as well as unforeseen. 'Confrontation' in Borneo is a euphemism for a bitter little war, sustained largely by Britain at the cost of a million pounds a week and over a hundred casualties. What is worse is that it is a war in which 'victory' is impos- sible, and to which we seem indefinitely com- mitted.

There are now ten battalions of British and Gurkha troops, and a Malaysian brigade in Borneo. They are spread out, a platoon at a time, along a tenth of undemarcated and sometimes disputed frontier, which if imposed upon the map of Europe would stretch from London to Warsaw. The terrain defeats description; it is surely the worst country in the world.

The Indonesians bold the initiative. They choose the time and place of an attack, usually upon an up-river village, which will have been fortified and is defended by the Security Forces. As the numbers committed are small, Indonesian casualties remain light, and include a proportion of Chinese. From their point of view, the incur- sions are worth while when seen in terms of the effort expended and in the fear and disrup- tion caused among the native peoples.

We now have enough troops in Borneo. If, however, the threat were to grow, we would be hard put to it to cope. Reinforcements would have to come from Malaya, whose own security problem threatens to get worse, or from Hong Kong, which has its own difficulties, or from Germany. We have not yet got enough soldiers in the all-regular army. President Sukarno has, from his standpoint, rather too many. The Indo- nesian army numbers 350,000 men, only a frac- tion of which is in Borneo, and which Sukarno dare not, for political reasons, disband.

A military solution could be achieved if British troops were allowed to attack and destroy Indonesian bases in Kalimantan. Air strikes against both the bases and the lines of com- munication and supply would be very effective. Such action is, however, ruled out for two reasons. Firstly, for fear lest the conflict escalate, and Singapore be bombed in retaliation; and, secondly, American disapproval owing to their not unnatural reluctance to be drawn into any wider conflict.

The war in Borneo is a helicopter's war and the number available is a matter of political controversy. The fact is that, at present, Borneo has every helicopter squadron save two, one of which is in BAOR and the other training pilots in Britain. Besides the RAF, there is a Royal Navy squadron and the Army Air Corps, who are handicapped by the grounding, owing to lack of spares, of all their scout helicopters. All the Auster light aircraft pilots are now being taught to fly helicopters, and it will not be until the autumn that more helicopters will arrive in the theatre. Until then the Air Force, from Mr. 1-high Fraser downwards, will remain sensitive on the subject; for their explanations have not always been as well received, especially by the Army, as they would have wished. While it is perhaps fair to say, as does the RAF, that the Army can never have too many helicopters, it is true that up to noW the Army has had too few.

A requirement exists for a counter-insurgency aircraft. In Vietnam the Americans are using old piston-engined Skyraiders for ground attack. Modern jet aircraft suffer from various disad- vantages. Their use is sometimes politically un- acceptable, reaction time is slow, since they operate from bases 300 miles behind the front line. Their high speed is a handicap, and their endurance, once over the target, is limited. What is needed is a light strike aircraft that earl operate from jungle strips, with machine-guns, rockets and bombs and which would, conceiv- ably, be flown by pilots of the Army Air Corps.

What the Army needs above all else is to

reduce the weight of rations and equipment that the soldier has to carry. His pack, which weighs 90 lb., should, ideally, be reduced to 45 lb. There are no dehydrated rations, the General Purpose Machine-Gun is too heavy, the stan- dard rifle could well be replaced by the Ameri- can Armalite, which is only half the weight. The new army radio set is heavier than its latest Australian equivalent, which is designed for the Jungle. Australian lightweight sleeping equip- ment, approved for the British Army in 1963, has not yet arrived. New, lighter-weight uniforms and webbing would be welcome. The jungle is not only hot, it is hilly; and if he is to be fully effective the soldier's load must be lightened. When the Federation was first mooted in 1961 it was seen in a multiple role. It would solve the problems of a predominantly Chinese Singa- pore; it would facilitate the decolonisation of the British territories of North Borneo; and it would, as the Federation promised. to be staunchly anti-Communist, increase the stability of the area. Above all, it would allow for the decent withdrawal of Britain from South-East Asia (with the prospect of a base in Australia to replace Singapore). Is three years too short a time to compare promise with performance? The Singapore experiment has been markedly successful. The island is effectively and decently governed by the People's Action Party under the Premiership of Lee Kuan Yew. But relations between the PAP and the ruling Alliance Party M Kuala Lumpur are strained. There are some Within the Alliance who are wary of the ad- Ministrative success and incipient multi-racial appeal of the PAP, which they regard as a pos- sible alternative government for the Federation.

It is hardly surprising that there should be some disenchantment within Borneo itself. Federation has brought with it war, higher taxes and the replacement of British administrators by Malaysians, a process in which quality is likely to be sacrificed in favour of keeping up appear- ances. There is dismay that the white man's burden should have proved so heavy. Malaysia is certainly anti-Communist. Whether its creation has made the creation of a resolute anti-Communist grouping in the area more diffi- cult is a matter of dispute. Washington, sees India, the countries of South-East Asia and Indonesia as a strategic counterbalance to China. Thus America's reluctance to become involved, and her search for the via media with initiatives such as Robert Kennedy's and support for N'IaPhilindo—a looser, wider confederation of the three Malay States of Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. One wonders if there has not been, on

ritain's part, a failure to think through the Implications of her policy. Malaysia, created by ilritain to facilitate her withdrawal, has now be- come a military commitment of indefinite duration. It is a commitment to a war that tannik be won, and which, when viewed in the Fontext of Chinese expansion. cannot but be irrelevant. We have been none too lucky with faur Federations.

Previous page

Previous page