THEATRE

Look forward in anguish?

KENNETH HURREN

John Osborne tends to be a bit testy about reviewers (or critics, as he is wont flatteringly to call them) and there's another engagingly venomous diatribe against them worked blandly into his new play, West of Suez. Nevertheless, if he can bear the masochism, he can probably best take the measure of the play's failure by reading the reviews. I don't mean, of course, its commercial failure; it will pack the Royal Court and later, perhaps, a West End theatre, and rightly so, because Osborne's failures are more stimulating than most dramatists' successes and he's always worth two and a half hours of anyone's time; but we'd all be sadly disappointed in him if, despite the grand town house and the easy life-style, he was a commercial man at heart. I don't mean, either, the bad reviews; mean the good ones, the laudatory splurges from the real well-wishers, because I doubt whether any of .them has touched more than the fringe of what this play they liked so much is conceived by its author to be about. Chekhovian parallels were obvious enough to draw (even without the photograph of Osborne-in-the-Russian manner in the programme). In other respects the failure in communications has been depressingly apparent.

Don't look at me for much enlightenment; I'm groping as much as anybody and I'd like to see it again. There is, I suspect, a great deal between the lines, and I'm not sure I was looking between the right lines. Knowing how it ends, I'd know, second time around, what to be listening and looking out for along the way. The trouble with a play, as opposed to a book, is that you can't flip back a few pages to check a point; you have to see it again, and most people just see it once.

This one begins with a variation on the antique formula of the Edwardian playwrights with their butler-and-parlourmaid patter designed to give the audience essential background information about who's staying in the house and who's coming to luncheon, flicking in some bizarre interest-hooker such as the peculiarity of the family's male line, afflicted with eleven toes since the days of William and Mary. Osborne gives us the Gillman family set-up through the bickering of one of its daughters and her husband — a protracted, spiky duologue scraping away at the scars left by old marriage wounds. They're a fascinating pair, and I find it hard to think of them merely as butlerand-parlourmaid expositors. The fact is, though, that their relationship and their troubles have no organic connection with the ensuing drama, and I can only assume that their significance somehow eluded my scrutiny.

Before we get in to the rest of it, the title seems worth considering, if only because no one else has remarked on it, and Osborne is not given to labelling his works with the random nonchalance of an action painter. The play is set on some unidentified island, recently released from the British colonial yoke, and its location has been generally taken to be the Caribbean, which is certainly 'west of Suez.' I doubt whether this island is specifically anywhere (if Osborne had the Caribbean in mind, there would be no reason for him to be cagey about it), and its symbolic position I take to be not so much geographical as chronological, not only 'west of Suez' but after Suez ': that is to say, after the Suez crisis, the ignominy of the gunboats and the diplomatic watershed that Osborne sees as the point of no return in the decline of Britain's imperial influence. It is a return to a theme explored first in Look Back in Anger; and later in The Entertainer — set, if memory serves, at the time of the Suez crisis, when Archie Rice's father, symbol of the old England, re-enlisted and died. Archie himself, a flyblown comedian, was doing his best to keep the Empire show going but time was running out. For Wyatt Gillman, central figure in West of Suez, another joker but urbane with it, the show is all over; all that remains is for someone to blow up the theatre.

Wyatt is a novelist, famous but not especially distinguished, a bit selfdeprecating, the runt of his family (I'm slipping in any information that may be significant) who had been sent not to Eton like the rest of them, but only to Marlborough (make what you will of that). He's the last of his male line, for his four children — sired, inevitably, at various points of the globe — are all daughters. They're all here on the island, holidaying at the villa-home of one of them (mistress, apparently, of a retired brigadier), and the only one with children of her own is the one who is married out of her class — to a provincial schoolmaster. There are so many tinkling symbols in all this, there's hardly room for the sounding brass, but it blares out eventually — when the villa's indolence is invaded, first by a penetrating interviewer from the local newspaper (exposing the gap in understanding between old Wyatt and the aspirations of the emergent islanders), then by a foulmouthed passing hippie (castigating them all to the limits of his restricted vocabulary), and finally by a couple of native guerrillas who cut the last umbilical cord with old Mother England by machinegunning Wyatt to death.

This is the colonial story, seen remotely in the earlier plays, moved on to location: to an outpost of the old empire itself where the remnants of a dead civilization are sustained by American technology (also dying, if we're to take Harry, the resident American engineer, as its symbol) and by American tourists who are already snapping pictures of the residents and their homes as they might be snapping the ruins of Athens or Rome. There was a feeling in Look Back in Anger and The Entertainer that Osborne was searching for the new credo that would be the salvation of England and us all, but things haven't quite gone the way that Jimmy Porter's hectoring might have driven them, and Osborne, edging into middle-age, allows himself some regret for the values that are being swept away (" My God, they've shot the fox!" is his last symbol, as Wyatt lies dead on the lawn) and some alarm over what may be taking their place.

But I have seen the play only once, and my barks may be directed up the wrong trees. It's hard to say, confidently, where Osborne stands in this situation, or who, if anyone, among these characters, is his spokesman. Does he look forward in anguish? Or in hope? Or is he cannily withholding judgement west of Suez, waiting for a new shuffle? Just as he has grown oddly self-conscious about the literacy of his dialogue ("That's rather good, that last sentence — has a sort of syntactical swing to it," remarks someone, and Osborne would never have felt the defensive need to have anyone say any such thing to Jimmy Porter), he would seem also to be recoiling from corn mitment. Somehow Osborne had seemed impervious to the uncertainties that assail so many radical spirits in their maturity. That he is not (or, at least, at a single sitting at the play, seems not) is the major disappointment of West of Suez, though the erratic nature of the construction is another, and the abruptness of the final violence — for which nothing that goes before is adequate preparation — seems to me a sizeable technical flaw.

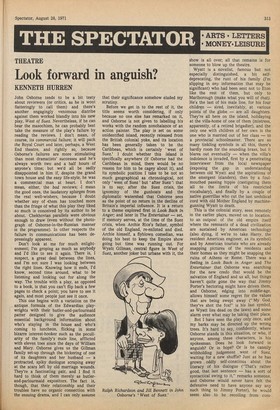

If I have reservations about the play, I have none at all about the brilliance of Anthony Page's direction (or orchestration) and precious few about the acting. The admirably chosen cast has Ralph Richardson as its centripetal force giving a masterly portrayal of the old fox, Wyatt, aware, behind his flippancy, that he is sitting on a powderkeg while society is playing with matches. He and Sheila Burrell put on a magnetic show in Wyatt's pivotal encounter with the island interviewer, when each vulnerable response hangs dangerously in the air like a loaded shuttlecock waiting to be hit.

Previous page

Previous page