Fiction

Short is beautiful

Peter Ackroyd

London Magazine Stories 9 edited by Alan Ross (London Magazine Editions £2.75) Winter's Tales 20 edited by A. D. Maclean (Macmillan £2,95) If the boring prophets of doom turn out to be right for once in their lives, we may be returning to those Elizabethan tribal days when poems were sold in loose-leaf form, and when pamphlets were distributed on street corners. 1, for one, would welcome the change; now that our leading publishers have turned poetry into a national joke, the best work is already being printed in mimeographed form, and, to judge by the quality of these two collections, the short story is now beginning to outrank the longer and sometimes more wasteful novel, London Magazine Stories is the more substantial collection, and this must in large part be due to the efforts of Alan Ross who, despite a strange predilection for American radicals, is a discriminating and successful editor. But Winter's Tales is by no means a small achievement, and it says a great deal about the vitality of the much abused 'AngloSaxon tradition' that this twentieth volume should contain some very good work indeed.

And over those last twenty years naturalism has become a finely tuned instrument, thus jcaomnfeosu Joyce a

g the oe egnbce`minondinergn' critics who saw of all things. The cvoeirylectfiiornst, Francis in thethge London Magazine 'The Fence', is an example of h story ow a natty realism can convey the most secret fears and obsessions without fuss and with no loss of power. Old acquaintances meet and in the process those smooth laws of chronology, which never apply to anyone except strangers are broken not by violence but by the written Story, although for order. It is a nicely' w rY, although from time to time Mr King lays out his theme too candidly for its own good, and it demonstrates that a cool and careful English prose can reach a great deal further than the 'hang-out' school of romance.

It says

something about our 'situation' (presuming that e have one nowadays) that some of the best stories in this book are written

m fro or about t foreign soil. David Pownall and George Moor have two very powerful stories set in Africa, n it is only in this ow the black man's burden, since spot that those old fictional themes pastoral , sex and violence, can find a spiritual home. And, as art extension to this shift of emphasis

, it is the foreign writers in this book who handle the English language with an almost proprieto

prison-life in South Africa,

rial air. Bessie Head's story of 'The Prisoner Who Wore Glasses', has a simplicity and a directness which our more jaded nationals have all but abandoned, and Dina Mehta's story of a plain man's triumph

i

in Mehta h over his intellectual wife, 'The Other Woman', s as old as the Indian hills but, 's —ands, as witty and intelligent a

study of man's inhumanity to woman as you could hope to find in a month of English Sunday reading. The Empire is no longer, of course, the only bearer of cultural tidings since the best story in this book is one that has been translated from the Korean, 'The Winter of 1964, Seoul' by Seung-Ok Kim; it is the history of one night in a city, where three strangers discover the bathos of it all. This might be the plot of any number of foreign stories, but it is impossible to summarise the power which Mr Kim lends to his theme. He combines a meticulous attention to the surface detail — "Meanwhile the flames swiftly licked the third last letter. I hoped the fire would soon catch up with the very first letter and that nobody in the crowd would notice the process of fire spreading up the signboard except me. . The white pigeon dropped into the fire" — with a current of private feeling which never quite finds its resolution:

He looked at me and inquired reflectively "Mr Kim, we are twenty four years old are we not?

"Well, I am".

"I am too." He shook his head. "I'm afraid",

Within the artifice of the short story, Mr Kim has preserved the dialogue and the more formal rituals of his culture, and in this abbreviated form they are at the same time more exposed and more triumphant. The short story cannot move very far or very fast, and it is as well to understand the formal aspects of the medium before you use it; John Fuller has exploited its limitations very effectively in `The Bunker', a study in the slow growth of a mental illness. Each episode becomes an epigram, but there are glimpses of a universal hell within each private mood.

The short story, at its best, is a conceit and you ignore its strict boundaries at your peril. I am afraid that some of the writers in Winter's Tales do just that, and there is a certain amount of slackness and indiscipline around the edges. Susan Hill is by no means a slack writer, but she can be obsessive one; her story in this collection, 'Kielty's', has too much power for its own good, and constantly thereatens to spill out beyond its rather narrow bounds. But Sean O'Faolain provides the perfect antidote, with a very witty story of one writer's search for some romance in sexuality; Mr O'Faolain has a great deal of fun in exorcising that particular phantom, which is now reserved for sociologists. The short story has never been adept at

presenting these more lyrical moments in a novelist's canon, and Frank Tuohy has managed, in An Evening in Connecticut' to turn some particularly private psyches into an objective and 'social' world. He is a very intelligent, albeit literary writer, and the theme becomes a theorem which Tuohy never quite manages to solve, But I liked his thirteen pages very much indeed.

If you want to transgress the bounds of the short story altogether, I suggest you read the last of this collection, 'The Massacre of the Innocents' by James Harris. If you forgive the fact that this is labelled a 'work in progress' (we would normally prefer to see the real thing), and if you overlook some boyishly literary moments, you will come across a witty and very nearly accomplished writer. His is an exuberant prose which redeems the occasional note of whimsy — "The earth was so good and so popular that the seeds had to put their names down on a special waiting-list . . ." —and although he sometimes writes with more heat than light it is all done with great charm and verve. It proves that the language is still capable of dancing, and both of these volumes, in their different ways, demonstrate' that there are still editors who can recognise that fact and that there is still a public to appreciate it.

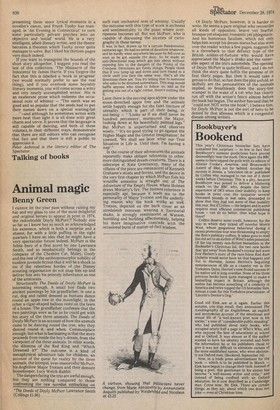

Peter Achroyd is the literary editor of The Spectator.

Previous page

Previous page