Talking of books

Animal magic

Benny Green

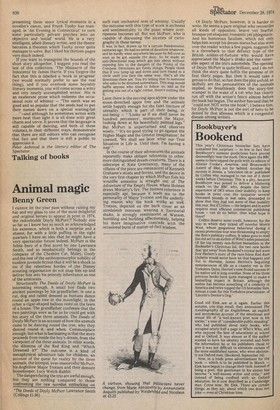

I cannot let the year pass without raising my hat and my glass to one of the most delightful and original heroes to appear in print in 1974, the redoubtable Doyly McPurr.* Nobody else so far as I know has so much as acknowledged his existence, which is both a surprise and a shame, for with a little puffing in the right quarters I have an idea that he might have a very spectacular future indeed. McPurr is the feline hero of a first novel by one Lawrance Smith, and so emphatically belongs in the company of the Cheshire Cat, Moley, Goofy and the rest of the anthropomorphic nobility of modern juvenile fiction that it will be a shock to me if the relentless hordes of the Disney scouting organisation do not snap him up and deliver him into his princely inheritance as one of the aristocats.

Structurally The Deeds of Doyly McPurr is interesting enough. A small boy finds two ancient paintings by his grandfather; in one a cat, dog and rabbit dressed as humans dance round an apple tree in the moonlight; in the other a cigar-shaped balloon rests on the lawn of a house. The grandfather confesses that the two paintings were as far as he could get with his story of the three animals. The Deeds of Doyly McPurr is an account of-how the animals came to be dancing round the tree, why they danced round it, and when. Commonplace enough; but what is fascinating is that the story proceeds from inside the boy's dream, from the viewpoint of the three animals. In other words, the dilemma of the Red King and "Which Dreamed it?" The outcome is a kind of metaphysical adventure tale for children, an account of the quest for reality by the three animals, the intrepid, ever-resourceful McPurr, his dogfellow Major Trotson and their demure housekeeper, Lucy Welch-Rabbit.

The dangers facing the trio are awful enough, but they are nothing compared to those confronting the raw novelist embarking on

*The Deeds of Doyly McPurr Lowrance Smith (Collings £1.95)

such vast uncharted seas of whimsy. Usu'ally' the outcome with this type of work is archness and sentimentality to the point where overripeness becomes all. But not McPurr, who is capable of discussing the niceties of cartography in these terms:

It was, in fact, drawn up by a certain Randomulus, centuries ago. He had no sense of direction whatever, and be hardly went anywhere because he fell over as soon as he got outside the door. So he made an anti-Directional map which got him about without exposing him to the dangers of the Points of the Compass. Directions are funny things. People think that if you jump up and down and turn round in a circle until you face the same way, that's all the directions there are. You try telling that to someone who asks to be directed somewhere. This map would baffle anyone who tried to follow us, and as for getting you out of a tight corner, there's nothing like it.

Later there is the moving apocalypse under the moon-drenched apple tree and the animals settle happily enough for the faint tincture of unreality which is part of their being, or not-being — "'Looks as if we shall never be hundred percenters', murmured the Major, looking down at his beautifully painted legs." But McPurr is unperturbed and observes wisely, "'It's no good trying to go against the Higher Magic and the Greater Imagination', he yawned, 'We shall see later what our True Situation in Life is. Until then, I'm having a nap'." In the course of their adventures the animals repeatedly make oblique references to other, more distinguished dream-creatures. There is a sideswipe at Kate Greenaway, many of the villains of the piece are reminiscent of Kenneth Grahame's stoats and ferrets, and the device in the very first chapter by which McPurr thus his wouldbe assassins is straight out of The Adventure of the Empty House, where Holmes draws Moriarty's fire. The Holmes reference is especially apt, because it leads me to the personality of Major Trotson and the underlying reason why the book works so well. Trotson, depicted on the back cover as an airedaleish innocent wearing a Territorial shako, is strongly reminiscent of Watson, bumbling and burbling affectionately, helping his more imaginative comrade with the occasional burst of matter-of-fact wisdom.

Of Doyly Mc Purr, however, it is harder to write. He seems a pure original who reconciles all kinds of opposites; brave yet fearful; brusque yet eloquent; romantic yet phlegmatic. And his humorous fatalism, which not only helps him accept his dream-status but also wins over the reader within a few pages, suggests he is a throwback to that defunct type of the British soldier-of-fortune who would have appreciated the Major's shako and the venerable aspect of the trio's automobile. The opening of Doyly McPurr is quite brilliant, and I do not think the story quite fulfils the promise of its first thirty pages. But then it would take a genius to do that, so fast does the plot unfold, sO skilfully are the personalities of the animals implied, so breathlessly does the story-line scamper in the wake of a cat who has clearly run off with the writer's fancy almost before the book has begun. The author has said that he "could not NOT write the book"; I believe hinl, for Doyly McPurr is not the sort of hero to be denied by that idleness which is a congenital disease among writers.

Previous page

Previous page