Buying the Shareholder

By JACK MALLOCH

THE name of Mr. Hugh Fraser has become widely known in recent years because of his increasing capacity to absorb drapery and allied businesses. In the major centres of population in Scotland many of the biggest stores and many famous firms still carried on under their former names are now the property or under the control of The House of Fraser. In many cases these re-

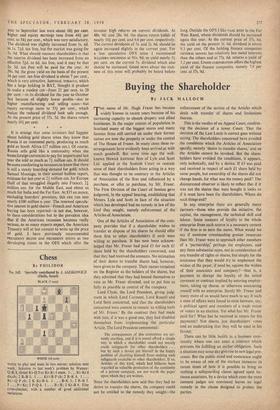

arrangements have evidently been arrived at with much goodwill. But some time ago the well- known Hawick knitwear firm of Lyle and Scott Ltd. applied in the Scottish Court to restrain some of their shareholders from acting in a way that was thought to be contrary to the Articles of Association of the firm and influenced by a purchase, or offer to purchase, by Mr. Fraser. The First Division of the Court of Session gave judgment, in the appeal hearing, establishing that Messrs. Lyle and Scott in face of the situation which has developed had no remedy in law of the kind they sought, namely enforcement of the Articles of Association.

One of the Articles of Association of the com- pany provides that if a shareholder wishes to transfer or dispose of his shares he should offer them first to other shareholders if such were willing to purchase. It has now been acknow- ledged that Mr. Fraser had paid £3 for each £1 share held by the shareholders concerned, and that they had received the amounts. No intimation of their desire to transfer shares had, however, been given to the company. Their names remained on the Register as the holders of the shares, but they admitted that they had bound themselves to vote as Mr. Fraser directed, and to put him as fully as possible in control of the company.

Lord Clyde, the Lord President, giving judg- ment in which Lord Carmont, Lord Russell and Lord Sorn concurred, said that the shareholders concerned were content to remain 'as willing tools of Mr. Fraser.' By the contract they had made with him, if it was a good one, they had disabled themselves from implementing the particular Article. The Lord President commented :

The consequences of this contention are cer- tainly startling, and if it is sound afford a simple way in which a shareholder could not merely evade safeguards for other shareholders . . . but by such a device put himself in the happy position of disabling himself from making such safeguards available to other shareholders, If so, Articles of this kind, which had hitherto been regarded as valuable protection of the continuity of a private company, are not worth the paper upon which they are written.

Since the shareholders now said that they had no desire to transfer the shares, the company could not be entitled to the remedy they sought-the

enforcement of the section of the Articles which deals with transfer of shares and limitations thereto.

This is the verdict of an Appeal Court, confirm- ing the decision of a lower Court. That the decision of the Law Lords is correct goes without saying. The shareholders concerned have avoided the conditions which the Articles of Association specify, namely 'desire to transfer shares,' and so the Articles cannot be invoked. But the share- holders have avoided the conditions, it appears, only technically, and by a device. if £3 was paid and received in respect of each £1 share held by some people, but ownership of the shares did not change hands, for what was the money paid? The disinterested observer is likely to reflect that if it was not the shares that were bought it looks as if it must have been the shareholders. Where do such things end?

In any enterprise there are generally many partners-those who provide the initiative, the capital, the management, the technical skill and labour. Some measure of loyalty to the whole enterprise from each source is a necessary cement if the firm is to earn the name. What would we say if someone commanding greater resources than Mr. Fraser were to approach other members of a 'partnership,' perhaps the employees, and pay them substantial sums, not in consideration of any transfer of rights or shares, but simply for the assurance that they would try to implement the wishes of the payer, if need be, against the wishes of their associates and company?-that is, a payment to disrupt the loyalty of the initial covenant or contract implied by entering employ- ment, taking up shares, or otherwise associating oneself with an enterprise. Surely Mr. Fraser and many more of us would have much to say if such a state of affairs were found to exist between, say, a political agent and members of a trade union or voters in an election. Yet what has Mr. Fraser paid for? What has he received in return for his payments? Not shares, just shareholders' votes and an undertaking that they will be used in his favour.

There can be little health in a business com- munity where one can enter a contract which prevents his fulfilling an earlier obligation. Such a situation may some day give rise to new legal pro- cesses. But the public mind and conscience ought to be aware of one of the starkest instances in recent times of how it is possible to bring to nothing a safeguarding clause agreed upon be- tween associates, by a device which even the most eminent judges are convinced leaves no legal remedy in the clause designed to protect the parties.

Previous page

Previous page