Going Dutch Andrew Lambirth delights in the Nation

Going Dutch Andrew Lambirth delights in the National Gallery's exhibition of a Golden Age J've been reading Still Life with a Bridle by the poet Zbigniew Herbert in preparation for Dutch Portraits: The Age of Rembrandt and Franz Hals at the National Gallery. It's a fascinating collection of essays which examines and pays tribute to the Golden Age of Dutch art and the society that produced it. Packed with unusual and stimulating perceptions, not to mention poetic inventions, the book only increases one's sense of wonder at such an efflorescence of talent concentrated in one unprepossessing place over a relatively short period. (This exhibition covers the years 1599-1683 and runs until 16 September, sponsored by Shell.) Herbert quotes a contemporary description of the Dutch as 'merchants of butter who milk cows in the trough of the ocean, and live in forests they have sown themselves, or in swamps changed into gardens'. He comments: 'Who could fail to notice in this sentence an unintended note of admiration?' And it was with admiration that I found myself touring the National Gallery's latest show.

Back we are in the basement of the Sainsbury Wing, the brief moment of showing temporary exhibitions in the daylightflooded upstairs galleries now but a happy memory of Velazquez and (to a lesser extent) Renoir. But it has to be said that these Dutch portraits look pretty good downstairs — it's a highly enjoyable show of some 60 works (a very good size), with a decided sprinkling of masterpieces. Inevitably the chief attractions are going to be Rembrandt and Hals, but there are plenty of other things to look at as well, and some lesser names to become familiar with. In these days of terrorist threat it is remarkable that so many great paintings are permitted to venture from the protective cocoon of their museums and risk the air passage to foreign venues. We must be grateful to the Mauritshuis in The Hague, and the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, for loaning such treasures as 'The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp' and 'The Syndics (De Staalmeesters)', but then we will be reciprocating. This exhibition travels to The Hague (13 October 2007 to 13 January 2008), and the National Gallery will lend eight pictures. Pray for their safe return, and for that of all loaned paintings which travel the globe in troubled times.

At the beginning of the exhibition, the visitor is greeted by an unconventional circular portrait of the future ambassador and jurist Hugo Grotius, by Jan van Ravesteyn. This is chronologically the earliest painting in the exhibition yet looks surprisingly modern — a bony, wakeful, intelligent face which might have belonged to some scabrous wit of the 1920s. On the far wall behind this precocious young man is a marriage portrait by Franz Hals, a typical subject of the period, celebrating what was for many the key event between birth and death. Note the rather saucy, knowing look on the bride's face, and the satisfied smile on her husband's; they at least appear to have found felicity. Nearby is a strangely stilted family group by Cornelis van der Voort, in which the father proffers a pear like a prize for good behaviour. An informal portrait of Charles I by Gerrit van Honthorst depicts the monarch looking oddly naïve with marble brow and blushing cheeks, against the bright sage green and carnation of his costume. A pair of early Hals portraits adds to this fine introduction to the show.

Room 2 sees the exhibition really get into its stride. Start with Hals's 'Portrait of Willem Coymans', who looks a bit of a bounder as he turns to you, his right arm cocked over the chair-back. Notice the fluidity of technique and innate theatricality that have led some to think of Hals as superficial. Going round the wall, it's quite a contrast to encounter the friendly, down-to-earth face of Pieter van den Broecke, also portrayed by Hals. As the painter John Bellany has observed, 'Ha's seems to be able to paint people looking happy without being cloying ... This is a very rare thing in great painting.' And talking of great painting, it's time to encounter Rembrandt. There are three paintings here by that consummate master, but perhaps the most moving is the portrait of the 83-yearold widow Aechje Claesdr, rendered with a technical virtuosity equalling if not exceeding Hals, mingled with a depth of feeling and compassionate understanding unique to Rembrandt. On the opposite wall is 'The Anatomy Lesson', which at first glance always looks more gory than it actually is. (It's the arm being dissected, not the guts.) A great and amazing group portrait, here compared with the altogether more posed 'Osteology Lesson of Dr Sebastiaen Egbertsz' by Nicolaes Pickenoy.

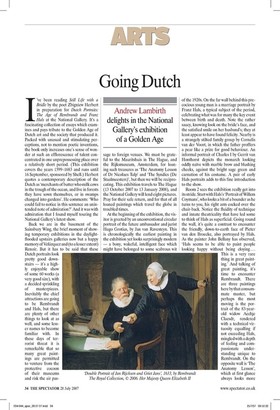

To the left of these surgical subjects hangs a grand full-length portrait of Willem van Heythuysen, a wealthy textiles merchant depicted in full commanding mode. On the opposite wall is a much smaller painting of the same subject, relaxed enough to be tipping back in his chair, done ten years later. Both are by Hals, the life-size portrait being the only single figure he painted like that, evidently preferring the increased intimacy possible in a smaller study. Move through into Room 3 for a brush with the theme of the family, exemplified by the double horror of a baby portrait of twins by Salomon de Bray. The best thing here is Hals's surprisingly beguiling 'Portrait of Catharina Hooft and her Nurse', in which the pleasant-looking nurse easily comes off best. There are also a stuffed and characterless couple by Thomas de Keyser, and the wonderfully showy 'Portrait of Jaspar Schade' by Hals, in which the paint veritably sizzles down the brocade sleeve of the right arm, and quite makes up for the snootiness of the sitter.

In Room 4, the substantial painting of officers and guardsman of the 11th district of Amsterdam, known as 'The Meagre Company', extends along the end wall. Composed and much of it painted by Hals, it was completed by Pieter Codde, who had a much smoother touch altogether. Despite the joint authorship, the painting brilliantly activates a vast horizontal surface and makes a splendid foil for the other, more sombre, group portraits in this room. Down the left side of the gallery three paintings are lined up: Rembrandt's 'Syndics', Hals's 'Regents of St Elisabeth's Hospital' and Bartholomeus van der Helst's 'Regents of the Voetboogdoelen'. These three paintings alone offer enough material for an exhibition. However, it's no surprise to find the Rembrandt the most compelling of the trio, both for the quality of the paint and the manifest human understanding. It is with a sense of light relief that one turns to the portrait of Johannes Verspronck's standard-bearer, magnificent in pink satin with blue sash and ensign, his gloved hand knuckled on padded hip, elbow jutting out at the viewer in a gesture of 'here — pay attention, you'.

Room 5 is perhaps the high point of the whole show. Rembrandt's 'Portrait of an Elderly Man' is a work of genius. Look at the depthless experience in the eyes and the way the sitter grimly holds on to the status quo in the face of death. A marvellous piece of painting which is a great human statement, and curiously uplifting. Likewise the unexpected serenity in the faces of Jacob Trip and his wife Margaretha de Geer. They make van der Helst's double portrait opposite look no more than a classy fabric study. After that, the last room can only be an anticlimax, though it does contain an amusing genre scene by Jan Steen (knew he'd get in somehow) pretending to be a portrait, and another small Hals, of an unknown preacher, which has an arresting intensity. An exhibition to return to.

Previous page

Previous page