A Supernatural Windfall A Time To Keep Silence. By Patrick

Leigh Fermor. (John Murray, 15s.)

THIS book, short though it is, divides itself, Gaul- like, into three parts. There is a chapter on the deserted Rock Monasteries of Cappadocia. Of the life there we know nothing—we do not even know how they came to be deserted—and of them Mr. Leigh Fermor can only give us an architectural description. If he wished to compare Byzantine monasticism with Western, it is not clear why he did not go to some existing Greek monastery such as Hosios Loukas in Phocis. Then there is a section on La Trappe. but this is again only history and objective description. The discipline of the Trappists prevented him from personal contacts and the secret of the Trappists—what is the reason why some with a vocation prefer their extreme austerity to what Mr. Fermor clearly thinks of as the more mellowed rule of the Benedictines'?—he confesses that he has not yet discovered. The personality of de Ranc6 is repulsive to him.

It is with his residence in the Benedictine monasteries of St. Wandrille and Solesmes that the bones of this book are concerned. He chanced to have those experiences in France, but, as he truly says in his postscript, the experiences would have been much the same in an English monastery There are historical passages and passages of description of the monastic life. These are in- cidental. The essential question of the book is, What is the point of monasteries? Mr, Leigh Fermor describes how on hi S first arrival at St. Wandrille he was oppressed with a feeling of immense desolation, as if he was the only living being wandering through a necropolis, but how, as time passed, his feeling came to be exactly the opposite—a feeling that here alone was reality, a feeling of immense peace in freedom from the distraction of trains and telephones, con- tinual chatter, the noise, the dust, the racket and the worry of the world; and how on his return to the world the vulgarity of it all—of the hoard. ings of the advertisements in particular—seemed to him unendurable. But, to judge the value of such emotions, we must, he argues, decide what is true. Is grace a reality? Does anything really happen when we pray? If prayer is meaningless —and it would be interesting to know how many even among sincerely believing Christians do really in their heart of hearts believe that any- thing objective happens when they pray—then we can indeed say of monks that by their quiet. unaffending life at least they do no harm, which is more than can be said of many of their fellow- men but their life is necessarily a very negative life, an escape from reality. And indeed, for all the nonsense that is talked about 'escapism,' it is certainly true, as Mr. Fermor argues, that no one who did not -utterly believe in the reality and power of prayer would either be allowed to remain a monk or would wish to remain one. That being so, the persistent survival of monas- ticism through the centuries should in itself cause those who so easily assume that prayer is unreal to pause a little in their judgement.

Yet, though a man must be a great fool if in face of the strength of evidence he denies the reality of prayer, yet there are few who would not be even more foolish if they felt confident that they understood very much about it. Some critics have complained of Mr. Fermor's book that it is too short and scrappy. He makes it clear that it is so of purpose. He could easily have bulked it out with longer history—more detailed accounts of the Benedictine rule—ampler quota- tions from the great masters of the spiritual life.

But the book that he has chosen to write is a book of personal experience, and a book of personal experience of a mystery only to the threshold of Which he has, by his own confession, been able to penetrate. Brevity is a deliberate and worthy confession of humility. He says little because he knows little.

He was, he tells us, .'hindered by several dis- abilities from sharing to the utmost all the advantages a stranger may gain from monastic sojourns.' Nevertheless, he was able to discover 'a capacity for solitude . . . and for the "recol- lectedness" and clarity of spirit that accompany the silent monastic life. For in the secluSion of a cell . . . the troubled waters of the mind grow still and clear, and much that is hidden away and all that clouds it floats to the surface and can be skimmed away; and after a time one reaches a state of peace that is unthought of in the ordinary world. This is so different from any normal experience that it makes the stranger suspect that he has been the beneficiary . . . of a supernatural windfall or an unconsciously appropriated share in the spiritual activity that • is always at work in monasteries.'

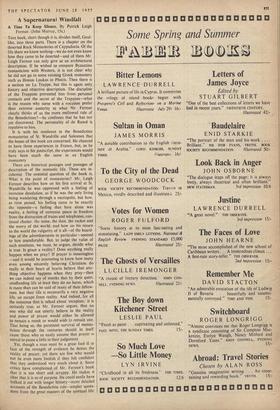

The book is beautifully illustrated, but it is a pity that it is marred by an inordinate number of misprints—particularly in the French and Latin quotations.

- CHRISTOPHER HOLLIS

Previous page

Previous page