The Price of Gold

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT UNTIL I, received a few tart letters on my recent critique of the international payments system I had no idea how strongly some people felt about the official price of gold. The fact that the American authorities stubbornly refuse to think of adjusting the price at all—much less of doubling it or trebling it—appears to make these critics mad and vent their rage on poor me who have merely despaired of getting American bankers to see reason. A long time ago I was advocating the raising of the price of gold and I still think that on balance—given the right time—the advantages of it outweigh the disad- vantages. But I feel that it is waste of time dis- cussing it any longer while the possessors of the big gold hoards—the Americans and the Common Market Europeans—dominate the International Monetary Fund. I am confirmed in this view on reading that the successor to the late Dr. Per Jacobsson as director-general of the Fund is none other than M. Schweiter, of the Banque de France, who has been described as expressing 'the narrowest economic orthodoxy.' The rigid and reactionary banking clique in control of the IMF will allow no tampering with their gold mystery. They will dismiss any radical reform coming from the British, even if voiced by poli- ticians as respectable as Mr. Maudling or Mr. Harold Wilson, as the vulgar atternpt of a chronic debtor to increase his overdraft without collateral.

But to return to the price of gold. When the Americans fathered the birth of the IMF in 1946 they got the directors to accept the gold price of $35 an ounce which had been fixed by President Roosevelt in 1934. The directors then got the members of the Fund to fix and publish their ex- change parities in terms of the gold dollar. They stated at the time : We recognise that in some cases the initial par values that are established may later be found incompatible with the main- tenance of balanced international payments posi- tions at a high level of domestic activity.' Sir Stafford Cripps proved the wisdom of these cau- tionary words when he solved a grave economic crisis at home by devaluing the £ by 30+ per cent in September, 1949 (from $4.03 to $2.80), thus raising the sterling price of gold by 44 per cent— from 172s. 3d. to 248s. an ounce. (The present London market price is around 250s.) The rest of the sterling area followed his lead and the opportunity was then taken by France, Belgium, Italy and Portugal to effect lesser devaluations of their own currencies. No further upset occurred until 1958 when General de Gaulle, with the con- nivance of the IMF, wrote down the franc from 864 to 1,062. Later—in March, 1961—Germany and Holland up-valued their currencies by 5 per cent—and have regretted it ever since. In that year—as in 1957—there was a sharp attack on the £ and our exchange parity was only saved by heavy borrowings from the IMF and by prompt support from the centrat banks. In this uneasy period the feeling grew that if the £ were allowed to go it would bring down the dollar and the whole IMF system would collapse. It thus became taboo to talk of raising the price of gold. Indeed, when a rumour of further currency devaluation spread in October, 1960, and the price of gold on the free London market was forced up temporarily to $40 an ounce through the pressure of private demand an arrangement was quickly made between the British and American authorities whereby the Bank of England could draw on Fort Knox for gold whenever the private hoarding demand exceeded the supply of new gold from South Africa. Last year the hoarders took no less than 75 per cent of the new supply, which seems to indicate a stubborn belief that the official price of $35 cannot be held indefinitely.

There is undoubtedly some force in the hoarders' view. The longer the arthritic IMF system creaks on, the longer the gold powers refuse to improve international liquidity either by writing up the price of gold or by turning the IMF into a note-creating 'super' central bank which could help finance the development of the poor half of the world, the surer will come the great exchange crisis of the West—the crisis when the export industries of the industrial nations fail to find sufficient credit-worthy buyers overseas to maintain their precarious balance of payments.

America seems to be bringing this day nearer. Her export industries and services may provide a healthy surplus over her import bill, but her defence commitment overseas and her foreign aid saddle her with a payments deficit of around $2,000 million a year. This has to be paid for ultimately in gold, with the result that her gold reserves which were as high as $22,837 million in 1957 have now been reduced to under $16,000 million. What she has lost has gone mainly to augment the gold reserves of the European 'surplus' nations—now over $12,000 million. (The UK reserves remain under $3,000 million.) She makes matters worse by clinging to that

archaic rule of the old gold standard which is to have a gold backing for her internal currency. Her present internal gold ratio is 25 per cent, requiring about $12,000 million worth of gold. Deducting this from the reserves, she has under $4,000 million free gold to set against foreign dollar deposits of $20,000 million. As the mone- tary authorities could not meet a private run on their gold 'bank' they have been careful to come to an understanding with the European gold powers that the dollar holdings of their central banks will not be converted into gold at Fort Knox. Of course, if a flight from the dollar into gold were to develop on the part of non-central bank holders the authorities at Fort Knox would have to put an embargo on further sales and the dollar price of gold on the free market would soar. But the Federal Reserve appears to be con- fident that such a panic will never occur, that too many people who own dollars realise that the gold game has to be played with restraint. But what a silly game it is! Doubling the price of gold without a reform of the IMF might even make it sillier—making the gold powers more powerful. No one wants a gold boom while half the world starves. Surely what is wanted before the price of gold is raised is a remodelling of the IMF, making it a deposit-creating world central bank.

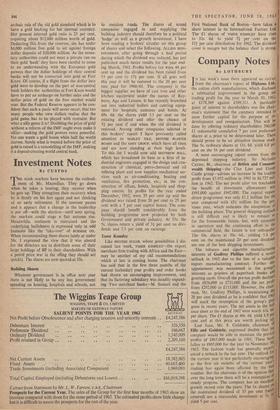

Previous page

Previous page