Hemlock and after

Elwyn Jones

The Dangerous Edge Gavin Lambert (Barrie and Jenkins £4.50) Naked is the Best Disguise Samuel Rosenberger (Arlington Books £2.95) The best crime fiction is anticipatory, even prophetic, and it gets harder and harder to write "as violence grows at once more extreme and more commonplace." That is Mr Gavin Lambert's thesis, and this humble practitioner does not choose to dispute it. For in matters criminal, nature has not so much imitated art as outstripped it. One of the genuine professional terrors of writing for the mass audience of television is to be overtaken by a criminal event four months after one has imagined and written. it and just two days before transmission.

The solution, Mr Lambert seems to suggest, is to provide more "analysis after the fact that intuition before it", but he buttresses this notion only with In Cold Blood, and even this he considers gets its "extraordinary tension" from the relation Truman Capote sensed between "a particular act of violence and his own life." Blessedly he does not analyse that relationship, for narcisissm would otherwise make cowards of several of us.

I've put the thesis first because the publisher's blurb does, but its statement and discussion occupy fewer than five of the book's 270 pages. The rest are devoted to discussion and illustration of how "in touching off some of our deepest fears, the major 'crime-artists' also certainly looking at or imagining another reveal their own." This is fearsome Wound and the Bow territory into which Mr Lambert plunges boldly. He sketches the lives and careers of Wilkie Collins, Conan Doyle, G. K. Chesterton, Eric Ambler, Simenon, Graham Greene, John Buchan, Alfred Hitchcock, and Raymond Chandler, and finds something pretty odd about all of them, from Collins's appearance to Chandler's devotion first to his mother and then to a wife substantially older than he. -Mr Capote should consider himself fortunate to have been spared the full treatment.

This is handed out in fairly breathless continuous-present prose. Some• examples: "Until his wedding night Chesterton remains a virgin, in itself probably a struggle . . "Although he dismisses instrospection as 'morbid', John Buchan reads a good deal about psychoanalysis. In his middle thirties he develops a painful duodenal complaint that treatments and an operation fail to cure . . . Buchan is known to have endured his condition with a minimum of complaint. Almost certainly he accepted it as another element of ordeal . ." "In 1930 aged seventy-one Doyle has a second attack of angina pectoris. It leaves him mute during his last hours but he signs to be lifted from his bed and placed in an armchair. His wife and his youngest son each hold his hand. He remains like this for a long time, gazing out of the window to the garden. He is almost certainly looking at or imagining another country." Unless of course he was just lodking, or brooding about a dog, or Sherlock Holmes, or what some bright screenwriter and novelist might eventually imagine about him.

Mr Lambert might well have pondered Raymond Chandler's claim (which he quotes) that far more art goes into crime-fiction "than any number of fat volumes of goosed history or social-significance rubbish." He might then also have avoided a flat-footed literalness which makes me suspect that the book is either a prelude or a postscript to a set of lectures on "creative crime-writing" which Mr Lambert has either given or is about to give on some not very sophisticated American campus. How else explain the ponderous pedantry of "The Copper Beeches and The Reigate Puzzle describe the greed of affluent people and today their impulses would be classified as aggression by Conrad Lorenz and as the territorial imperative by Robert Ardrey."? Still, nit-picking is neither pleasurable nor profitable, and Mr Lambert's book is a lively enough introduction to some of the writers. It is also generous with its quotations. For example I had not previously encountered Eric Ambler's discerning comment that "the detective story may have been born in the mind of Edgar Allan Poe, but it was London that fed it, clothed it, and brought it to maturity." Curiously Mr Lambert devotes little attention to Poe. But he had his own rich insights and then perhaps said it all with "Nor was I indeed ignorant of the flowers and the vine, but the hemloek and the cypress overshadowed me, night and day."

Samuel Rosenberg is an altogether jollier fellow, not a scriptwriter, but with important film links. "For many years I'd worked as a literary consultant for a major motion-picture studios which hired me when they were sued for plagiarism. I analysed the embattled scripts, and when the resemblances between 'theirs' and 'ours' were too close for comfort, I tried to get my employers off the litigious hook by searching for the common literary ancestors of both properties, It was fascinating work, I received much praise, and one employer even dubbed me 'a literary Sherlock Holmes.' "So let Conan Doyle beware. Mr Rosenberg establishes profound associations between Doyle and Holmes and an initial list of twenty-four real-life, fictional, legendary, and Biblical 'figures ranging from "Jesus Christ as the Superstar of the Easter celebration of his Death and Resurrection", through George Sand, "author and transvestite", to the Reverend Ward Beecher "the American clergyman, almost defrocked."

It's all good raunchy stuff and very educational too. It isn't every author who "assumes that very few readers in 1903 — and even fewer in 1974 — would be likely to recognise 'journeys end in lovers' meetings' as a line from Twelfth Night." At that level Mr Rosenberg is quite a literary detective.

But he's humble -though. He ends, "I have found that the Do lean allegory discovered here and unfolded was once anticipated and perfectly stated by John Donne." That said perfect statement occupies, precisely three lines of verse. Mr Rosenberg's book runs to 198 pages. Among his previous books is The Confessions of a Trivialist. So he's honest too.

Elwyn Jones has been the principal writer of such television programmes as Z Cars, Softly Softly, Task Force and Barlow

Previous page

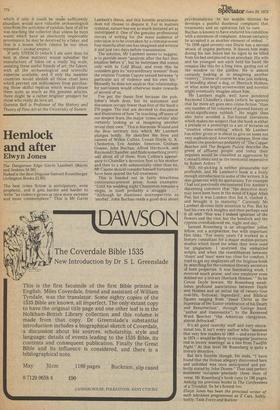

Previous page