The dying had to stop

Byron Rogers

BOGART

by A. M. Sperber and Eric Lax Weidenfeld, £20, pp. 676 It was an extraordinary career. By the time he had completed his first 45 films he had been hanged or electrocuted eight times, sentenced to life imprisonment nine times and riddled with bullets 12 times. Then he stopped dying. The crumpled vil- lain became an even more crumpled hero, and Humphrey Bogart in late middle age found himself a 20th-century legend.

But then he did have every advantage when it came to his chosen career, being frail, with a scarred lip and a lisp, and from a family in which his parents, rich New York socialites, were both alcoholics and drug-addicts: he would have been glad to see the back of real life. And, to give him credit, he persevered with his advantages, marrying four times, once to an alcoholic who stabbed him, and becoming an alcoholic himself. In those rare moments when the piano stopped he seems to have been a nice, kind man.

This is a work of monumental research, based on a quarter-ton of research material (someone weighed it) amassed by Ann Sperber who died in the course of it, having taken seven years to interview everyone who had met him, including a lift man in the hotel where he once stayed. All this was inherited by Eric Lax who then wrote a book in which the notes alone occupy 75 pages. And for what?

So you can read about a man whose working life consisted of not being himself, of speaking dialogue written for him by others and assuming moods to their direc- tion. Does anyone want to read 676 pages about an actor?

Well it seems I did, for I finished it and, though the book would have been none the worse for a cut of about a third, enjoyed it. I come from a generation fascinated by such men as Bogart. We saw their films in cinemas (there was none of the familiarity of television); we saw them in darkness perhaps twice a month, and so the gods walked and talked for us. They will not do so again. Nobody in his right mind is going to write 676 pages about the life of Bruce Willis in 50 years time. Certainly nobody would want to read it.

This biography left me with a sense of wonder about the films I saw, for somehow the psychopaths who ran the studios, the drunks who starred and the men who wrote dialogue in the backs of cars on the way to work, between them made films which, in spite of their efforts, aspire to art. We remember scenes; we even remember lines we have never seen written out:

`And what in heaven's name brought you to Casablanca?'

'My health. I came for the waters.'

`Waters? What waters? We are in the desert.' `I was misinformed.'

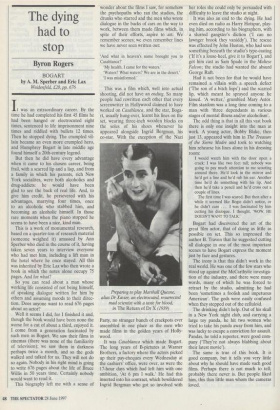

This was a film which, well into actual shooting, did not have an ending. So many people had rewritten each other that every screenwriter in Hollywood claimed to have worked on Casablanca, and the star, Boga- rt, usually hung-over, learnt his lines on the set, wearing three-inch wooden blocks on the soles of his shoes whenever he appeared alongside Ingrid Bergman, his co-star. With the exception of the Nazi Preparing to play Marshall Quesne, alias Dr Xavier, an electrocuted, resurrected mad scientist with a taste for blood, in The Return of Dr X (1939) Party, no stranger bunch of crackpots ever assembled in one place as the men who made films in the golden years of Holly- wood.

It was Casablanca which made Bogart. The long years of B-pictures at Warner Brothers, a factory where the actors picked up their pay-cheques every Wednesday at the cashiers' office, were over, as were the 17-hour days which had left him with one ambition, 'At 6 pm I walk.' He had this inserted into his contract, which bewildered Ingrid Bergman who got so involved with her roles she could only be persuaded with difficulty to leave the studio at night.

It was also an end to the dying. He had even died on radio as Harry Hotspur, play- ing him, according to his biographers, with a slurred gangster's diction CI can no lawnger brook they vaniddy'). The rescue was effected by John Huston, who had seen something beneath the studio's type-casting (If it's a louse-heel, give it to Bogart'), and got him cast as Sam Spade in the Maltese Falcon; the studio had wanted the absurd George Raft.

Had it not been for that he would have remained a villain with a speech defect (The son of a bitch lisps') and the scarred lip, which meant he sprayed anyone he kissed. 'A wetter,' grumbled Mary Astor. Film stardom was a long time coming to a man with 'three dependants in various stages of mental illness and/or alcoholism'.

The odd thing is that in all this vast book there is only one insight into the man at work. A young actor, Bobby Blake, then just 13, appeared with him in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and took to watching him rehearse his lines alone in his dressing room: I would watch him with the door open a crack: I was like two feet tall; nobody was going to pay much attention to me scooting around there. He'd look in the mirror and he'd get a line and he'd rub his ear. Another time he'd do something with his lip. And then he'd take a pencil and he'd cross out a couple of lines.

The first time I was scared. But then after a while it seemed like Bogie didn't notice, or he didn't care .. . I was fascinated by him cutting his dialogue. I thought, 'WOW, HE DOESN'T WANT TO TALK' Bogart had discovered the art of the great film actor, that of doing as little as possible on set. This so impressed the author B. Traven that he suggested cutting all dialogue in one of the most important scenes to have Bogart express the moment just by face and gestures.

The irony is that this didn't work in the real world. He was one of the few stars who stood up against the McCarthyite investiga- tion of the industry, and there were many words, many of which he was forced to retract by the studio, admitting he had been 'sometimes a foolish and impetuous American'. The gods were easily confused when they stepped out of the celluloid.

The drinking didn't help. Out of his skull in a New York night club, and carrying a large toy panda, he hit two women who tried to take his panda away from him, and was lucky to escape a conviction for assault. Pandas, he told a reporter, were good com- pany (They're not always blabbing about their latest movie').

The same is true of this book. It is good company, but it tells you very little about why he should have made such good films. Perhaps there is not much to tell; probably there never is. But people liked him, this thin little man whom the cameras loved.

Previous page

Previous page