Notebook

was after we had gone to press last week that the following announcement was issued by the Press Association: 'Agreement has been reached today whereby Mr Algy Cluff will buy the Spectator from Mr Henry Keswick. Mr Alexander Chancellor will continue as editor, retaining, as before, Complete editorial freedom'. A nice, succinct statement and one to which it is remarkably difficult to take exception. This may be a little disappointing to readers who enjoy the spectacle of journalists parading their consciences and have been looking forward to a leading article entitled 'Unacceptable or, at the very least, 'Ourselves'. I would, indeed, have rather enjoyed having a go at writing one if Mr Cluff had not so inconsiderately spiked all my guns. If one is asked to stay on as editor and simultaneously offered complete editorial freedom, it is hard to work up the necessary indignation. Nor is there any chance of the excitement which a referral to the Monopolies Commission might arouse. Mr Cluff, I calculate, could purchase every journal of opinion in the country — and Private Eye as well — without .running the risk of infringing the monopolies legislation, for their combined circulations would not exceed the required 500,000. So we have little alternative but to sit back and be grateful that this paper to which we are all S o attached has been bought by a man who Shares this attachment and who, to use his Own words, sees himself as a protector rather than an interventionist. When one considers the plight of other similarly vulnerable magazines — Encounter being a topical example — one begins to feel very grateful indeed.

It is impossible, however, to acquire a new proprietor without losing the old one, and if there is reason already to feel grateful to Mr Cluff there is even greater reason to be grateful to Mr Keswick, under whose benevolent protection we have been labouring for nearly six years. The question about the Spectator which seems to interest :People most is why anybody wishes to own it. It is a perfectly reasonable question, given that the paper has not been profitable for many years, but one to which no satisfactory answer is ever available. Either the purchaser may not really know why himself, or he may be secretly following the practice of my grandmother who, when her motives for doing something were ques tioned, would engagingly reply: won't give you my real reason, but Pll give you another one which will do just as well'. In My view there are mysteries which no wise man should probe, and the motives of Spectator proprietors are one such mystery. What matters to the Spectator's journalists is not only that they should enjoy the security which, in present circumstances, only a rich proprietor can give them, but that they should be required to offer nothing in exchange other than the best of their abilities and their own honest judgment of what is interesting, entertaining or true. It sounds a very one-sided deal, and it is one that must at times be very exasperating for the proprietor. One could not blame him if he sometimes felt that in exchange for his generosity all he was getting was blame for the foolish opinions of others and the unwelcome attentions of gossip columnists with little or no regard for the truth. But the deal is not one-sided. The proprietor who interprets his role, whether intentionally or not, as the protection of the freedoms of others will not only go to heaven in due course; he will preside over a much better magazine than it would otherwise be, and he will earn the affection, loyalty and esteem of all kinds of unlikely people. This is what has happened to Henry Keswick. And, speaking personally, I find to my surprise that although I have known and liked him all my life, it has been possible to work for him for six years and like him still.

I had not expected the Social Democratic party to damage my own interests even before it was born, but this is what it has done. In my own borough of Hammersmith it has seduced away a Conservative councillor, Mr Clive Killick and thereby helped impose a rate increase of 53.6 per cent, the second highest in the country. Mr Killick's defection to the Council for Social Democracy contributed to the defeat of the Tory administfation which had been proposing to raise the rates by 48 per cent, as if that were not enough. But the Labour opposition, which controls only one less seat than the Conservatives, wanted the bigger increase because it could not stomach the idea of making 160 people redundant and cutting expenditure by £6 million. The strange _ thing is that Mr Killick should have chosen such an unpopular cause as a colossal rate rise as his pretext for changing political allegiance, though it will no doubt be taken as a sign of compassion, integrity, and so on. I cannot say that I am as familiar as I should be with the arguments for and against the increase of 53.6 per cent, but I find the Tory 'budget co-ordinator', Mr David Clark, very persuasive when he calls for expenditure cuts. He told the Council: 'On books, printing and stationery, we spend £603,000 a year. Convert that into sheets of A4 paper and lay them end to end, and you can do four trips to Moscow or one trip to New York. We buy 54,545 light bulbs a year. We must be eating them'. Hammersmith Council already looks rather as Westminster may look in its future multi-party form. It is a spectacle of utter confusion, with the Tory administration — until its resignation this week — at the mercy of two Liberals (who actually managed to split on the rates vote) and two independents, one of whom, a woman, enjoys keeping her voting intentions secret until the last moment. Comparisons with the House of Commons are further encouraged by the Westminster-sounding names of Hammersmith's three party leaders — Howe, Powell and Knott.

Unless he expands his entry in Who's Who, Sir Richard Bruno Gregory Welby, 7th baronet, is likely to be publicly remembered for nothing but his vandalism. Who's Who records only that Sir Bruno was educated at Eton and Christchurch, that he has a wife, three sons and one daughter, and that he lives near Mrs Thatcher's home town of Grantham at Denton House in Lincolnshire. In a field on his estate there was once a group of 17th century almshouses, built of ironstone with grey stone dressings, and reputedly charming, with elaborate gables. But they are there no longer. Last December, after neglecting them for a number of years, Sir Bruno had them demolished. He may be rather out of touch, for he is said to believe that, because the buildings belonged to him, he had every right to pull them down. But things are not quite as easy as that. They were Grade II listed buildings, which meant that the Department of Environment considered them to be 'of outstanding interest' and would not have wanted them pulled down without permission. Now Sir Bruno is to be privately prosecuted by Mr David Pearce, Secretary of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. Magistrates,if they so choose, will be entitled to send Sir Bruno to prison for six months and fine him up to £1,000. If he is really unlucky, they could refer the case to the Crown Court, where the fine could be unlimited and the prison sentence could be as much as 12 months. With all these eager conservationists around it can really be no fun being a country baronet anymore.

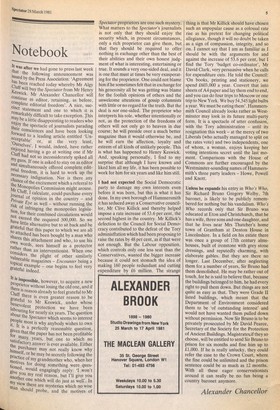

Alexander Chancellor

Previous page

Previous page