ARTS

The new English Shakespeare Com- pany, founded by Michael Bogdanov and Michael Pennington, and funded jointly by the Arts Council and the Allied Irish Bank, is a welcome enterprise. Given the guiding spirit of Michael Bogdanov, the company is bound to project itself as a populist endeavour — with 'relevance' and 'accessi- bility' high on the list of priorities. In this respect at least, it is slightly misleading to characterise it as an 'alternative' to the RSC or the National. Its frank populism, its willingness to coat the classics with sweeteners to help them go down — all this might well be described as the continuation of RSC policy by other means. But what it does have over the other two main subsi- dised companies is its own vital energy. This is especially evident if you watch all three plays in the ten-hour marathon sit- ting available on Saturdays. You can sense the company's belief in itself. Or, at least, what you do not sense is that feeling you find in the RSC at its worst: the tired, mechanical spirit of a giant institution fulfilling its production quotas. The Eng- lish Shakespeare Company are of course helped by being able to stage their cycle in a proper theatre like the Old Vic.

The principal justification for mounting these plays as a trilogy is to trace Hal's development from seemingly irresponsible Prince of Wales to scourge of the French at Agincourt. It is a growth from a state of apparent fecklessness to pragmatic king- ship. England is a divided nation and Hal's destiny is to end the intestinal shock of civil war and unite his people by the classic remedy of a foreign war.

We first encounter Hal's father, Henry IV, as he discusses policy with his suppor- ters. Most of us are probably used to seeing this early scene played as an intimate meeting of politicians anxious to reassure one another that they can hang on to the power they have recently usurped. Bogda- nov successfully directs it as a stage- managed media event where each speaker comes to the microphone and delivers his words in the manner of a canting party- political broadcast — complete with trium- phal music. Then, in the next scene, we hear Henry voicing his true private fears about Hal's preference for the company of Falstaff and the stews of Eastcheap. The succession is at stake because the heir apparent appears unfit to govern. Patrick O'Connell's monarch is a convincingly harsh, nervous and aggressive usurper. He is best in Part I, noisy and a little histrionic in Part II when on his deathbed.

Michael Pennington's Hal is a carefully paced and subtle study of the part. It is also completely orthodox. He knows he will

Theatre

Henry IV Part I, Henry IV Part II, Henry V (Old Vic) The Emperor (Royal Court Upstairs)

The price of kingship

Christopher Edwards

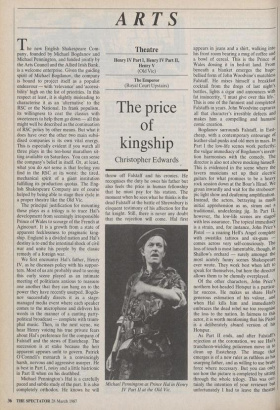

throw off Falstaff and his cronies. He recognises the duty he owes his father but also feels the price in human fellowship that he must pay for his station. The moment when he sees what he thinks is the dead Falstaff at the battle of Shrewsbury is eloquent testimony of his affection for the fat knight. Still, there is never any doubt that the rejection will come. Hal first Michael Pennington as Prince Hal in Henry IV Part II at the Old Vic. appears in jeans and a shirt, walking into his front room bearing a mug of coffee and a bowl of cereal. This is the Prince of Wales dossing it in bed-sit land. From beneath a blanket emerges the huge bellied form of John Woodvine's matchless Falstaff. He mixes himself a breakfast cocktail from the dregs of last night's bottles, lights a cigar and announces with fat insincerity, 'I must give over this life.' This is one of the funniest and completest Falstaffs in years. John Woodvine captures all that character's irrestible defects and makes him a compelling and humane comic creation.

Bogdanov surrounds Falstaff, in East- cheap, with a contemporary entourage of leather-clad punks and old men in macs. In Part I the low-life scenes work perfectly; the vulgar immediacy of Bogdanov's inven- tion harmonises with the comedy. The director is also not above mocking himself. This is evidenced in the scene where the tavern musicians set up their electric guitars for what promises to be a heavy' rock session down at the Boar's Head. We groan inwardly and wait for the strobosco- pic light show and deafening amplification. Instead, the actors, betraying as much initial apprehension as us, strum out a traditional, undeafening jig. In Part IL however, the low-life scenes are staged with less assurance. The topical immediacy is a strain, and, for instance, John Price's Pistol — a roaring Hell's Angel complete with swastika tattoos and six-guns comes across very self-consciously. The loss of touch is most lamentable, though, in Shallow's orchard — surely amongst the most acutely funny scenes Shakespeare ever wrote. They work best when left to speak for themselves, but here the director allows them to be clumsily overplayed. Of the other characters, John Price's northern hot-headed Hotspur is a partial' lar success. He makes us share Hal's generous estimation of his valour, and when Hal kills him and immediatelY embraces the dead rebel we too recognise the loss to the nation. In fairness to this actor, it is worth mentioning that his Pistol is a deliberately absurd version of his Hotspur. As Part II ends, and after Falstaff's rejection at the coronation, we see Hal's truncheon-wielding policemen move in to clean up Eastcheap. The image that emerges is of a new ruler as ruthless as his usurping father, and as willing to use brute force where necessary. But you can onlY see how the picture is completed by sitting through the whole trilogy. This was co' tainly the intention of your reviewer but unfortunately I had to leave the theatre early on in Henry V with a raging tooth- ache. I will however (at my own expense) return to see the final play — an economic decision which can be taken as a recom- mendation that this cycle is artistically worthwhile and interesting. There is space only to recommend the production of The Emperor at the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs. It is a stage version of Ryszard Kapuscinski's book based upon interviews held by the author With former servants of Haile Selassie after his fall from power in 1974. Supporters of the deposed emperor have denounced the book and this production as grotesque distortions of the truth. On the night I attended the theatre there was a bomb scare.

The book is brilliant, but it is not history. There is no attempt to explain the causality of events. It is an artistic impression, Perhaps a fantastic one, of the end of a regime. It gives us a picture of how power was wielded and lost at that court of Whispers, of how the emperor spied on everyone, of how political fortunes were made and unmade by a glance. The set is a series of secret doors and peepholes. The cast of five men is drawn from vanous African countries. Under Jonathan Miller they fashion a fascinating piece of theatre based, principally, upon simple spoken extracts from the book. It is a production that deserves to be seen more widely but which depends absolutely upon the col- laborative intimacy of a tiny theatre.

Previous page

Previous page