Exhibitions

The Art of Holy Russia (Royal Academy, till 14 June)

Spiritual grace

Martin Gayford

There is a case, of course, for saying that Byzantium didn't fall, with Con- stantinople, in 1453. Activities were simply transferred to other locations — principle among them being Moscow. That was the view of the late 16th-century Russian monk who claimed Moscow as the 'third Rome' — the first two, on the Tiber and the Bosphorus, having fallen, the last remained eternal. Certainly, there is a powerfully Byzantine feeling about the darkened rooms of the Sackler Galleries at the Royal Academy just now. The walls painted a rich, reddish purple and gleaming with the gold and silver of the exhibits in The Art of Holy Russia: Icons from Moscow 1400-1660.

Whether or not the Russians of the 16th century really saw themselves as the heirs to the Emperors of Byzantium is disputable — or at least is disputed by essays in the catalogue to this show. Possibly they merely borrowed titles and finery from far and wide. Many of the architects of the Kremlin came from Renaissance Italy, the double- headed eagles from the Austrian Habs- burgs, the title 'Tsar' — or Caesar — from Rome and Constantinople alike. But there's not much doubt that Russian paint- ing until the time of Peter the Great was a branch of Byzantine art (as was the art of the mediaeval Balkans, and parts of pre- Renaissance Italy).

Indeed, the temptation for newcomers to the subject is to take a rapid glance around and conclude that here is just another load of old icons. It is a temptation which, I think, should be resisted. But, on the other hand, Russian art was unquestionably high- ly repetitive — as was Byzantine art before it. And that was no accident. In the Renais- sance, in western Europe, artists often gained a positive dividend from individuali- ty and innovation; in Russia it might lead to trouble.

`He who paints an icon out of his imagi- nation shall suffer endless torment,' it was menacingly pronounced in 1658. Earlier, Ivan the Terrible — before turning full time to paranoia, massacre, sadism and savage persecution of his subjects — had applied his mind to the question of icon painting. What was the correct manner in which to paint the Trinity? the Tsar asked of an ecclesiastical council in 1551. 'In nothing,' came back the answer, 'should the painters follow their own fantasy.' Instead they should 'reproduce the ancient models, those of the Greek icon painters, of Andrei Rublev and other famous painters'.

Not surprisingly, therefore, one finds a good deal of compositional recycling in Russian art. To the left of the entrance in the Sackler Galleries there hangs a variant of Andrei Rublev's 'Trinity' — in itself an extremely beautiful work of art — painted almost a century after the original, but fol- lowing Rublev in almost every line. Throughout the exhibition one finds designs repeated almost exactly — the Christ Pantocrator, for example, from the centre of the iconostasis in his geometric Heaven of red and black.

Nonetheless, individuality and change did exist in Russian art. Andrei Rublev himself was a painter of the stature and distinctiveness of, say, Duccio — though an even more shadowy figure. Rublev, plus the expatriate Byzantine Theophanes the Greek and Dionysii, a Moscow master from the turn of the 16th century, rank with Malevich and Kandinsky as the great figures in Russian painting. (Cinema-goers will probably have seen Tarkovsky's over- whelming epic of a film, Andrei Rublev, which makes the viewer so heartily glad not

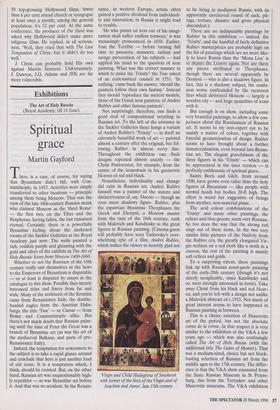

`Virgin and Child Hodegetria of Smolensk with scenes of the lives of the Virgin and of Joachim and Anna, late 15th century to be living in mediaeval Russia, with its apparently unrelieved round of sack, pil- lage, torture, disaster and gross physical discomfort.) There are no indisputable paintings by Rublev in this exhibition — indeed, the `Trinity', and the handful of fairly definitive Rublev masterpieces are probably high on the list of paintings which are no more like- ly to leave Russia than the 'Mona Lisa' is to depart the Louvre again. Nor are there any pieces attributed to Theophanes, though there are several apparently by Dionysii — who is also a shadowy figure. In fact, this is a shadowy subject, the confu- sion worse confounded by the recurrent fires which destroyed Moscow — largely a wooden city — and huge quantities of icons with it.

But enough is on show, including some very beautiful paintings, to allow a few con- jectures about the Russianness of Russian art. It seems to my non-expert eye to be mainly a matter of colour, together with forceful geometrisation of design. Rublev seems to have brought about a further dematerialisation, even beyond late-Byzan- tine art. The elegant gracefulness of the three figures in his 'Trinity' — which can be appreciated in the later version — is perfectly emblematic of spiritual grace.

Saints Boris and Gleb, from around 1500, have grown even taller than the holy figures of Byzantium — like people with normal heads but bodies 20-ft high. The effect is weird but suggestive of beings from another, non-material plane.

The acid colour combinations of the `Trinity' and many other paintings, the ochres and blue-greens, seem very Russian. So too does the way that the strong red sings out of these icons. In the two very similar little pictures of the Nativity from the Rublev era, the greatly elongated Vir- gin reclines on a red cloth like a moth in a cocoon, the rest of the painting is mainly soft ochres and golds.

To a surprising extent, these paintings link up with Russian avant-garde painting of the early-20th century (though it's not utterly inexplicable, since Kandinsky and co. were strongly interested in icons). Take away Christ from his black and red Heav- en, and you're left with a design not unlike a Malevich abstract of c.1915. Not much of great interest seems to have happened in Russian painting in between.

This is a choice selection of Muscovite art of the period, but not the absolute creme de la creme. In that respect it is very similar to the exhibition at the V&A a few years ago — which was also confusingly called The Art of Holy Russia (with the additional title The Gates of Mystery). That was a medium-sized, choice but not block- busting selection of Russian art from the middle ages to the 17th century. The differ- ence is that the V&A show emanated from the State Russian Museum in St Peters- burg, this from the Tretyakov and other Muscovite museums. The V&A exhibition was more wide-ranging, dealing with other centres such as Novgorod and Tver. This one sticks to Moscow. The present exhibi- tion is better mounted, in fact beautifully displayed. And, like its predecessor, it is well worth visiting. There is still scope, however, for a really big, top-quality Rus- sian art show in London. This isn't quite that.

Previous page

Previous page