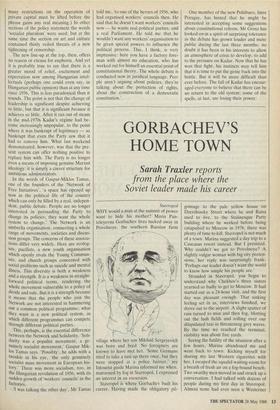

GORBACHEV'S HOME TOWN

Sarah Traxler reports

from the place where the Soviet leader made his career

Stavropol WHY would a man at the summit of power want to hide his mother? Maria Pan- teleyevna Gorbachev lives tucked away in Privolnoye, the southern Russian farm

village where her son Mikhail Sergeyevich was born and bred. No foreigners are known to have met her. 'Some Germans tried to take a taxi up there once, but they were stopped at a police barrier,' my Intourist guide Marina informed me when, marooned by fog in Stavropol-, I expressed an interest in an excursion.

Stavropol is where Gorbachev built his career. Having made the obligatory pil- grimage to the pale yellow house on Dzerzhinsky Street where he and Raisa used to live, to the Stalinesque Party building where he worked before being catapulted to Moscow in 1978, there was plenty of time to kill. Stavropol is not much of a town. Marina suggested a day trip to a Caucasus resort instead. But I persisted. Why couldn't we got to Privolnoye? A slightly vulgar woman with big city preten- sions, her reply was surprisingly frank: 'Perhaps our leader doesn't want the world to know how simple his people are.'

Stranded in Stavropol, you begin to understand why Chekhov's three sisters yearned so badly to get to Moscow. It had started out as a 24-hour visit, and the first day was pleasant enough. That sinking feeling set in as, interviews finished, we drove out to the airport. A slight spatter of rain turned to mist and then fog, blotting out the lush fields and rolling over our dilapidated taxi in threatening grey waves. By the time we reached the terminal, visibility was about five yards.

Seeing the futility of the situation after a few hours, Marina abandoned me and went back to town. Kicking myself for sharing my last Western cigarettes with her, I escaped the squalid waiting-room for a breath of fresh air on a fog-bound bench. Two swarthy men moved in and struck up a conversation. I had talked with dozens of people during my first day in Stavropol. Almost none had ever seen a Westerner

before.

This is the place from which Gorbachev rose to take America by storm last Decem- ber, to open up the Soviet Union to greater scrutiny than ever before as he proceeds with daunting reforms. In the light of glasnost, it seems all the more incongruous for Gorbachev to be so fiercely protective about his past. The French sovietologist, Michel Tatu, sees the answer in Gor- bachev's roots: For a long time, Mikhail Gorbachev will bear the burden of his origins in this deep province, in which everyone knows each other but is largely cut off from the outside.'

A town of 300,000, Stavropol lies in the rich agricultural steppe north of the Cau- casus. It was founded in 1777 as an advance garrison where Cossacks defended the southern rim of Russia. Appropriately, the surrounding territory is called Stavropol krai, which translates from the Russian to mean edge or brink. Once considered the gateway to the Caucasus, Stavropol was bypassed when a railway was built in the area in the late 19th century. Today it is definitely off the beaten track.

It takes 32 hours to cover the 1,000 miles to Moscow by train. Tourists are few, although more come these days, drawn by the Gorbachev factor. But once you have admired the profusion of roses along Karl Marx Prospek, (the main shopping street) and toured the market's abundant supply of fresh farm produce, there is little to do. The cracked pavements behind the market betray poverty. So do the public works going on near Gorbachev's former office, where they are tearing down the one- storey wooden frame houses which give Stavropol its charm. 'They don't have indoor plumbing,' Marina said. 'We need new modern flats.'

Privolnoye lies about 80 miles north- west of Stavropol. Gorbachev lived there from his birth in 1931 until 1950, when he left the region for the first time to study law in Moscow. His father drove a tractor on a collective farm, and when Gorbachev turned 18 they were both awarded the Red Banner of Labour for bringing in a good harvest. His mother, now in her mid-70s, is said to be a religious believer. There are rumours she had Gorbachev baptised in the Russian Orthodox Church. He goes back to see her once a year.

At Moscow State University, Gorbachev became the law faculty's Komsomol (com- munist youth) organiser and joined the Communist Party. Posted back to Stavro- pol in 1955, he was to stay there 23 years. quickly working his way up the hierarchy to become Party first secretary in Stavropol krai by 1970. At 39, he was the supreme overlord of a region nearly two-thirds the size of England.

In Stavropol, Gorbachev earned a repu- tation for openness and integrity. He walked to work through a park. and people told me he frequently stopped to chat. He took correspondence courses to obtain a second diploma, in agriculture, as his wife pursued a degree through pioneering sociological research on the lives of collec- tive farmers. In his capacity as a local Party boss, Gorbachev won the privilege of travel abroad. He and Raisa went to the West for the first time in 1966, covering 3,000 miles through the French countryside in a Renault. His travels also took him to Italy, Czechoslovakia, Belgium and West Germany.

He was protected as he made his way up the ladder by Fyodor Kulakov, who ran Stavropol krai for four years before his summons to Moscow in 1964 to oversee Soviet agriculture. But Gorbachev's prog- ress was also helped by his role as host of the region once he had become its first secretary. His duties included welcoming high-ranking travellers from Moscow on their way to the region's spas. One fre- quent visitor was Mikhail Suslov, a former Party leader in Stavropol who had risen to become the Kremlin's kingmaker. Another was the KGB chief, Yuri Andropov, his future patron, like Gorbachev a native of Stavropol krai. In one fate-charged meet- ing in September 1978, Andropov inter- rupted his holiday in the area to join Gorbachev in welcoming Leonid Brezhnev and his aide, Konstantin Chernenko, to Mineralniye Vody. The four men who met on the platform were to be successive holders of ultimate power in the Kremlin.

That meeting is viewed by historians as possibly decisive for Gorbachev. Kulakov had died in Moscow two months earlier. This left vacant the seat of Central Com- mittee secretary for agriculture, and in November 1978 Gorbachev was called to fill it. Already well-travelled by the time he got to Moscow, he gradually shed what was left of his provincial image as he advanced to the rank of General Secretary in March 1985. He lost weight, bought well-tailored suits and reportedly took diction lessons to take the edge off his southern accent. His long road from the farm in Privolnoye led him to the Washington summit and sup- reme power.

Previous page

Previous page