MATADORS OF THE MIND

Kasparov and Karpov are nearing the climax of a

three-year battle for the chess crown. Dominic Lawson

meets the players and takes the lid off the chess box

Seville SHAH MAT — the Shah is dead — said the ancient Persians who invented chess, and this has survived in corrupted English as 'checkmate', the chessboard's final solu- tion. In Seville, in the heart of barbaric Andalusia, where men are men and bulls are bulls, and both engage in ritual slaugh- ter, two foreigners are fighting to become the supreme matador of the mind, each trying to give 'mat' — or death — to the other. But the world chess championship between champion Gar- ri Kimovitch Kasparov and challenger Anatoly Yevgenevitch Karpov has come to resemble one of those bullfights which have gone on far too long, with the gory bull waiting helplessly for the final, botched, execution.

For the duel in Seville is the final encounter in a three-year struggle for intellectual supremacy, involving well over 100 games, and many more off-the-board moves and counter-moves of mutual character assas- sination.

'We are both ex- hausted,' Kasparov told me last week, just after he had moved into the lead in the 11th game of the present match, and the 111th of the whole series. 'Believe me, we are both trying to land a knock-out punch, but neither of us has the strength left to do it.'

But unlike boxers who have begun a bout as enemies and discovered respect for each other by the end of the final round, these two contestants started off with the surface friendship that characterises com- petition between good Soviet sportsmen, and have developed a very public antipathy that has scandalised the Soviet authorities. The grudge is mainly Kasparov's and stems from the sensational stopping of their first Moscow match in February 1985 by Kar- pov's close friend, Florencio Campo- manes, the President of Fide, the chess world's governing body. Kasparov's view, that Campomanes was rescuing Karpov from physical and mental collapse — and therefore defeat — after almost six months' uninterrupted struggle, is widely accepted in the chess world, by players on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

They also accept Kasparov's view that Karpov's excellent political connections with the apparatchiks of the Brezhnev era meant that the Soviet sports authorities were happy to connive with Campomanes' decision. The corollary is that Kasparov sees himself as a representative of glasnost, and has as his supporter in the Politburo Alexander Yakovlev, the Soviet propagan- da chief, and writer of Gorbachev's speeches.

But the structure of political support for the two players has had as much to do with race as with politics. The blue-eyed Slav Karpov always had strong support from the Moscow party machine, while the swarthy Azerbaizhani Kasparov relied on Geidar Aliev, the former head of the Communist Party of Azerbaizhan, and Soviet deputy prime minister, to help him fight on equal terms on the chessboard with Karpov.

If this remarkable, and so far unsupported, allegation is ever made public in the Soviet Un- ion, it will probably be in the law courts. About four months ago the Soviet Union promulgated laws which will allow Soviet citizens to take legal action in cases of defamation. Such are the costs, or benefits, of greater freedom of speech. Karpov is now studying Kasparov's auto- biography, Child of Change, in which Karpov is accused of all manner of foul practices. 'The book is all lies and I am aware of the legal situation,' Karpov said during the pudding. 'There are some in- teresting possibilities which I will look into after the match.' Which, translated, means 'If I win, I'll throw the book at him.' Kasparov conceded that his position if he lost the match 'is a hypothesis which I would rather not test in practice'.

But, in one area at least, the players are united in their opposition to the Soviet authorities: money. The prize fund in Seville is a record £1.2 million, to be divided five-eighths to the winner and three-eighths to the loser. This is equiva- lent at black market sterling/rouble rates to over 1,000 years' pay for the average Soviet worker. But whoever wins, it appears that the Sports Committee of the Soviet Union is set to make a killing. Under strict interpretation of Soviet law, the tax authorites should take 61 per cent of the prize fund, and the players would keep the rest.

But the Sports Committee has suddenly decided that it will take 61 per cent of what remains, leaving the players, according to Karpov, with only six per cent of the prize fund, once the Spanish authorities have taken their 20 per cent off the top. 'They did not tell us about this until after the match started,' Karpov fumed, 'because they knew that when the chess war began the players would be split.'

At the outset of the previous match between the two, which was played last year in London and Leningrad, both play- ers pledged the £600,000 prize fund to the victims of the Chernobyl disaster, giving much favourable publicity for the ethics of Soviet sportsmen and, by implication, the Soviet state. But in Seville last week Karpov revealed to me that about 90 per cent of that money had gone, not to the Chernobyl fund, but into the maw of the Soviet tax authorities and the Sports Com- mittee. 'That way, they can spend the money on whatever they like,' said Kar- pov, with the fixed smile with which he invariably masks his true emotions.

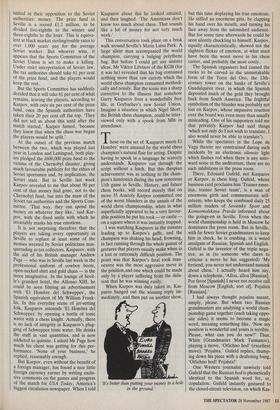

It is not surprising therefore that the players are taking every opportunity in Seville to replace at least some of the monies wrested by Soviet politicians mas- querading as tax collectors. Kasparov, with the aid of his British manager Andrew Page — who was in Seville last week in the professional uniform of cowboy boots, Open-necked shirt and gold chain — is the more imaginative. In the lounge of Sevil- le's grandest hotel, the Alfonso XIII, he could be seen filming an advertisement with 'El Hombre del Schweppes', the Spanish equivalent of Mr William Frank- lin. In this everyday scene of jet-setting folk, Kasparov astounds 'El Hombre del Schweppes' by opening a bottle of tonic water with a chess knight. Actually, there is no lack of integrity in Kasparov's plug- ging of Schweppes tonic water. He drinks the stuff in vast quantities, and is now addicted to quinine. I asked Mr Page how much his client was getting for this per- formance. 'None of your business,' he replied, reasonably enough.

But Karpov, even without the benefit of a foreign manager, has found a nice little foreign currency earner by writing exclu- sive comments on the games and progress of the match for USA Today, America's biggest circulation newspaper. When I told Kasparov about this he looked amazed, and then laughed. 'The Americans don't know too much about chess. That sounds like a lot of money for not very much work.'

This conversation took place on a brisk walk around Seville's Maria Luisa Park. A large silent man accompanied the world champion, carrying a bulging polythene bag. But before I could get any sinister ideas, Mr Viktor Litvinov of the KGB (for it was he) revealed that his bag contained nothing more than raw carrots which the world chess champion consumed methodi- cally and noisily. But the scene was a sharp corrective to the illusion that somehow Garry Kasparov lives a wonderfully free life, in Gorbachev's new Soviet Union. Imagine a situation in which Nigel Short, the British chess champion, could be inter- viewed only with a spook from MI6 in attendance.

Those on the set of `Kasparov meets El Hombre' were amazed by the world chess champion's natural flair for acting. Despite having to speak in a language he scarcely understands, Kasparov ran through the script without a hitch. But this thespian achievement was as nothing to the cham- pion's histrionics during the now notorious 11th game in Seville. History, and future chess books, will record merely that on move 35 Anatoly Karpov committed one of the worst blunders in the annals of the world chess championship, when in what superficially appeared to be a very favour- able position he put his rook — or castle — on a square where it was instantly trapped.

I was watching Kasparov in the minutes leading up to Karpov's gaffe, and the champion was shaking his head, frowning, in fact running through the whole gamut of gestures that players usually make when in a lost or extremely difficult position. The point was that Karpov's fatal rook man- oeuvre was the most aggressive move in the position,and one which could be made only by a player suffering from the delu- sion that he was winning easily.

When Karpov was duly taken in, Kas- parov banged out the winning reply im- mediately, and then put on another show, 'It's better than putting your money in a hole in the ground.' but this time displaying his true emotions. He stifled an enormous grin, by clapping his hand over his mouth, and turning his face away from the astonished audience. But for some time afterwards he could be seen silently chuckling to himself. Karpov, equally characteristically, showed not the slightest flicker of emotion, at what must have been the worst move in his chess career, and probably the most costly.

The Spanish organisers had caused the rooks to be carved in the unmistakable form of the Tone del Oro, the 13th- century tower on the banks of Seville's Guadalquivir river, in which the Spanish deposited much of the gold they brought back from South America. The frightful symbolism of the blunder was probably not lost on Karpov, whose impassive reaction over the board was even more than usually misleading. One of his supporters told me that privately Karpov had said things 'which not only do I not wish to translate, I also would never be able to translate'). While the spectators in the Lope de Vega theatre are constrained during such incidents by an electronic silencio light which flashes red when there is any unto- ward noise in the auditorium, there are no such inhibitions in the press room.

There, Edouard Gufeld, not Kasparov or Karpov, is chess king. Gufeld, whose business card proclaims him 'Trainer emer- itus, trainer Soviet team', is a man of enormous girth and commensurate self- esteem, who keeps the combined daily 25 million readers of Sovietsky Sport and Komsomolskaya Pravda informed about the goings-on in Seville. Even when the world championship is held in Moscow he dominates the press room. But in Seville, with far fewer Soviet grandmasters to keep him in check, he is crushing, in a weird amalgam of Russian, Spanish and English. Gufeld is the inventor of the triple nega- tive, as in (to someone who dares to criticise a move he has suggested) 'My frrriend, you never not understand nussink about chess.' I actually heard him say, down a telephone, `Alloa, alloa [Russian].

Por favor [Spanish] I never not receive call from Moscow [English, sort of]. Pojalsta [Russian].'

I had always thought pojalsta meant, simply, please. But when two Russian grandmasters are analysing a world cham- pionship game together (each taking oppo- site sides) it seems to become a magic word, meaning something like, 'Now my position is wonderful and yours is terrible. Please, what can you do now?' Thus, White (Grandmaster Mark Taimanov), playing a move, `Otlichno hod' (excellent move). Pojalsta.' Gufeld replies, thump- ing down his piece with a deafening bang, `Otlichno hod! Pojalsta!'

One Western journalist unwisely told Gufeld that the Russian hod is phonetically identical to the Spanish word for, er, copulation. Gufeld instantly gestured to the closed-circuit television, on which Kas- parov and Karpov were to be seen con- sidering their next moves: 'My frrriend, now you understand what men we Rus- sians are. Forty hods in one afternoon!'

But the farce in the press room was a bagatelle compared to that which de- veloped around the 15th game of the match last Friday, and which once again brought to the public's attention the extraordinary spite which exists between two of the Soviet Union's most idolised figures. The game itself was the best of the match so far, and was violent enough to prompt one normally restrained grandmaster to observe, 'They have turned out the lights and are attacking each other with axes.'

But, as so often in this class of chess, the most horrific complications finally resulted in a drawn position. This time the position was so prospectless that a well-trained ten-year-old could have drawn playing either colour against a team of Karpov and Kasparov combined. But Karpov insisted on adjourning the struggle, although the onus was on him, with an extra but useless pawn, to offer a draw.

Fifteen hours later and just four hours before the futile struggle would have been required to continue, Karpov finally offered a draw. But Kasparov was sleep- ing, or claimed to be, so now Karpov would have to wait and see if his Saturday would be ruined by a pointless chess game. After three hours of silence an enraged Karpov unprecedentedly withdrew his draw offer. This is rather like taking back a move in a world championship. Karpov insisted that the original offer was not authorised because it was made by his chauffeur, Vladimir Pischenko. This was disingenuous in the extreme. Pischenko, a member of 'a certain organisation', is also one of the senior men in the Karpov camp, and had for years acted as Karpov's gofer in the telephone transmissions of draw offers and even resignations. Karpov turned up on stage to continue the game, only to be told by the match arbiter, Geurt Gyssen, in full view of 150 goggling specta- tors, that he was declaring the game over, drawn, and there was nothing that Karpov could do about it.

My own enquiries suggest that when Pischenko called the Kasparov villa the phone was answered by the woman who does the cooking for the Kasparov entour- age. In fact two of Kasparov's grandmaster seconds were near the phone, and would have been prepared to agree to the draw offer immediately. But the cook, Catalina, said that the world champion could not be disturbed, and put down the receiver.

I sought to clarify the vexed question of the 15th match game with Grandmaster Josef Dorfman, Kasparov's chief second and former captain of the Red Army chess team. He explained, 'Karpov's chauffeur decided to offer a draw, but our cook declined to accept the proposal. My friend, why are you laughing? This is normal situation in world chess championship.'

Previous page

Previous page