THE CURRENT FAVOURITE

Margaret's men: a profile of

Lord Marshall, chairman of the Central Electricity Generating Board

This is one of a series of profiles of men whom the Prime Minister admires.

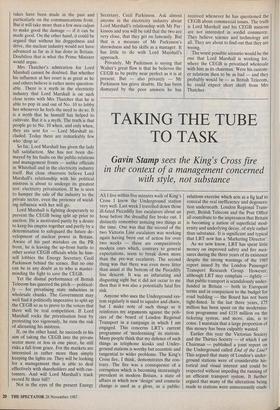

'THE trouble with Walter Marshall,' remarked one senior civil servant, 'is that he goes round thinking he can say things just because they're true.' Lord Marshall of Goring, physicist, chairman of the Central Electricity Gener- ating Board and Britain's 'Mr Nuclear Power', has never been known for his diplomatic skills. Yet his forthright, sup- remely self-confident approach — some would label it arrogance — has a strong appeal for the Prime Minister. Both of them regard nuclear power with fervent enthusiasm. Admittedly, he lacks the suave good looks to which Mrs Thatcher is so partial in her favourites. A large man Physically, his sheer size gives him a certain Presence — and when he turns up to industry meetings in full morning dress as he does in Ascot week, colleagues can find him positively awe-inspiring. Yet his move- ments are clumsy and his English accent seems, at first hearing, to owe more to Middle Europe than to his native Birming- ham.

But perhaps such oddities merely add to his charm. In his own unconventional way, Lord Marshall has more than the usual share of personal magnetism. For one thing, even his detractors admit there is not an ounce of malice in him — something that a non-comprehending Whitehall finds Peculiarly exasperating. More to the point, Lord Marshall is excellent company. He has the rare gift of being able to hold an audience — one person or hundreds — in thrall. And it is a valuable asset when dealing with Mrs Thatcher.

'One reason she likes him is because it flatters her self-image to sit down and have a scientific discussion with him,' said one Tory adviser. 'She has a chemistry degree and she likes to think of herself as a scientist. He, of course, is an eminent scientist. As such, he deals with facts. She finds that much more congenial than some of the opinions and speculation that others bring to her.'

But the main reason she likes him is that as far as she is concerned he is the man who kept the lights on during the miners' strike. Certainly the lights stayed on during the Scargill strike — and Walter Marshall subsequently collected a peerage. Yet there are plenty in the electricity industry who say it was not Lord Marshall but his deputy chairman at the CEGB, Gil Black- man, who kept the lights on. Brilliant scientist he may be, but Marshall is not and never has been an operations man. Furth- ermore, say the experts, he lacked Gil Blackman's abilities in man management as well as his technical expertise. Walter, they say, would have been more likely to give power station managers long lectures on the need to keep the current flowing than to cajole and bully them into doing the job. Be that as it may, Marshall must be given the credit for allowing the technical experts at the CEGB to get on with the task of generating electricity despite the pit strike. His predecessor as CEGB chair- man, Glyn England, would have been much more likely to find excellent reasons why the lights would have to be dimmed. It was under the chairmanship of Mr England that Mrs Thatcher was forced into a humiliating climb-down in the face of a threatened miners' strike in 1981. From that moment, the hunt was on for a tough-minded chairman who could be re- lied upon to take a sympathetic view of the Tory Government's position.

The search took some time. And Walter Marshall, who had been made chairman of the UK Atomic Energy Authority only the year before, was not top of the list of preferred candidates. Nor was he the Prime Minister's personal choice in any direct sense. In fact, he might more prop- erly be called Nigel's man than Margaret's, for it was Nigel Lawson, then Energy Secretary, who came up with his name.

He had a number of qualifications for the job — notably the fact that he was a nuclear power evangelist. He was also available. And he had managed to upset Labour's sometime energy secretary, Mr Tony Benn. In fact Mr Benn fired him from the post of chief scientist at the Department of Energy.

Probably, Marshall did not mean to upset Mr Benn by espousing the cause of British nuclear pressurised-water reactors. Probably, he also expected Mr Benn to be reassured — even joyful — when told that Britain's nuclear technology would find a ready market in Iran, under the right-wing regime of the Shah. But then Lord Mar- shall's ability to outrage people simply by speaking his mind has taken on a legendary quality over the years.

Take, for instance, his first dealings with the Electricity Consumers' Council. The Marshall hobby is origami — the Japanese art of making shapes out of paper. Walter had spent the first part of his first meeting with the electricity consumers folding a piece of paper into ever smaller pieces. When it finally came to his turn to speak, he stood up, put the tiny fold of paper to his lips — and blew it up into a bullfrog. As a party piece it was superb. As a way of persuading consumers that the CEGB chairman was on their side — it has long resisted the idea of having a board member for consumer interests — it lacked a certain something.

Civil servants at the Energy Department christened him Lord Sizewell of Elephant Trap when he acquired his peerage from a grateful Mrs Thatcher. 'It's not that Walter doesn't see the elephant traps people lay for him,' said one. 'He spots them every time — and walks straight into them.'

His reaction to the Chernobyl disaster was to give a public assurance to the effect that it couldn't happen here. And he was quite right technically — Britain does not have a Chernobyl-style nuclear reactor.

But the impression given to a disbelieving public was that human error — the cause of the Chernobyl tragedy — could not happen in Britain. 'One of the worst characteristics of the nuclear industry has been its arro- gance, particularly towards the public, and Walter has been one of the gravest offen- ders,' commented one industry insider. Today Lord Marshall admits that mis- takes have been made in the past and particularly on the communications front. But it will take more than a few mea culpas to make good the damage — if it can be made good. On the other hand, it could be argued that without his doggedness and drive, the nuclear industry would not have advanced as far as it has done in Britain. Doubtless that is what the Prime Minister would argue.

Mrs Thatcher's admiration for Lord Marshall cannot be doubted. But whether his influence at her court is as great as he and others believe is rather more question- able. There is a myth in the electricity industry that Lord Marshall is on such close terms with Mrs Thatcher that he is able to pop in and out of No. 10 to lobby her whenever he feels the need to do so. It is a myth that he himself has helped to cultivate. But it is a myth. The truth is that people go to No. 10 when, and only when, they are sent for — Lord Marshall in- cluded. Today there are remarkably few who 'drop in'.

So far, Lord Marshall has given the lady full satisfaction. She has not been dis- mayed by his faults on the public-relations and management fronts — unlike officials in Whitehall and in the electricity industry itself. But close observers believe Lord Marshall's relationship with his political mistress is about to undergo its greatest test: electricity privatisation. If he is seen to hamper the sale of the industry to the private sector, even the pretence of wield- ing influence with her will go.

Lord Marshall is fighting desperately to prevent the CEGB being split up prior to auction. He is motivated partly by a desire to keep his empire together and partly by a determination to safeguard the future de- velopment of nuclear power in Britain. Aware of his past mistakes on the PR front, he is leaving the up-front battle to other senior CEGB officials while he him- self lobbies the Energy Secretary Cecil Parkinson behind the scenes. But no one can be in any doubt as to who is master- minding the fight to save the CEGB.

Yet the dismal performance of British Telecom has queered the pitch — political- ly — for privatising state industries in wholesale chunks. The Government may well find it politically imperative to split up the CEGB so as to prove to the voters that there will be real competition. If Lord Marshall rocks the privatisation boat by protesting too vigorously, he runs the risk of alienating his mistress.

If, on the other hand, he succeeds in his aim of taking the CEGB into the private sector more or less in one piece, he still risks a fall from grace. For the markets are interested in rather more than simply keeping the lights on. They will be looking for a management that is able to deal effectively with shareholders and with cus- tomers. And will Lord Marshall's track record fit their bill?

Not in the eyes of the present Energy Secretary, Cecil Parkinson. Ask almost anyone in the electricity industry about Lord Marshall's relationship with Mr Par- kinson and you will be told that the two are very close, that they get on famously. But that is a measure of Mr Parkinson's shrewdness and his skills as a manager. It has little to do with Lord Marshall's approach.

Privately, Mr Parkinson is saying that Walter's great flaw is that he believes the CEGB to be pretty near perfect as it is at present. But — also privately — Mr Parkinson has grave doubts. He has been dismayed by the poor answers he has received whenever he has questioned the CEGB about commercial issues. The truth is Lord Marshall and his CEGB minions are not interested in sordid commerce. They believe science and technology are all. They are about to find out that they are wrong.

The worst possible scenario would be the one that Lord Marshall is working for, where the CEGB is privatised wholesale with him as its chairman. Were his custom- er relations then to be as bad — and they probably would be — as British Telecom, he could expect short shrift from Mrs Thatcher.

Previous page

Previous page