Gerald Durrell's A Zoo in my Luggage (Hart- Davis, 16s.)

tells of an expedition (his third) to the Cameroons, where he proposed to collect animals for his private zoo. I am not one for reading about animals (dirty, greedy and dumb), but Mr. Durrell contrives to win one's sympathy. This is partly because he writes extremely well, and partly because a large pro- portion of the book is in any case given over to the Africans he met, paramount among whom is the monstrous, many-wivcd, drunken and entirely amiable Fon of Bafut: this is a notable portrait, and inclines one to wish that Mr. Dur- rell, good as he is with his animals, would follow his brother into the urban jungle of man—though. I suspect that he is too nice to survive there long.

Pompeii and Herculaneum (text by Marcel Brion, photographs by Edwin Smith, Elek, 63s.) covers everything from the origins of those Unhappy cities down to the most recent excavations. The text, I apprehend, is rather prim, the early chapters in particular reading like a guide book especially prepared for Cook's when it was still a Temperance organisation. The whole, however, is scholarly and consequential, while the photographs strike a nice balance be- tween the instructive, the decorative and (very occasionally) the suggestive. In The Face of Ancient China (by W. and B. Horman, Spring Books, 50s.) the joint authors are responsible for both photographs and text. Their declared intention is to stick to ancient masterpieces an& archetypal landscapes and to avoid contemporary goings-on. I can only say that some of the photo- graphs are breath-taking (an expression I nor- mally eschew), but that the linked pensees, variously turgid, mock-humble and 'unworldly,' are enough to choke a Chinese camel.

SIMON RAVEN

Baroque Flavours

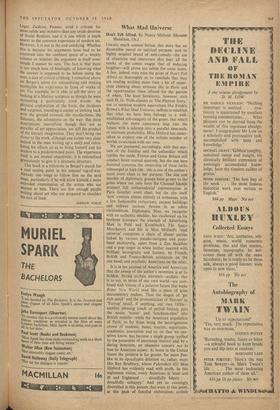

The Age of Grandeur. By Victor-L. Tapir (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 63s.)

IN recent years a number of French historians have tried to explore the relations between political, religious and social history and the development of the visual arts. Professor Braudel's great work on the Mediterranean in the sixteenth century and a number of extremely stimulating articles in Annales have strongly en- couraged this admirable trend. And now Profes- sor 'rapid's book on the Baroque has just been translated into English. It is, on the whole, well informed, clear and very readable, and should be looked at kindly and carefully by everyone in- terested in the seventeenth century. But it suffers from a number of defects that seem almost inherent in such studies. There is, first of all, the wide, unsupported generalisation. How do we know, for instance, that Baroque sensibility 'aroused a strong and enduring response' in the agricultural masses? They certainly weren't polled for their opinions. Then there are the question-begging assertions. It is meaningless to say that seventeenth-century systems of land tenure 'had a distinctly Baroque flavour.' Then

there is the extreme difficulty for an historian in keeping abreast of the specialist studies which are revolutionising our conceptions of Baroque art. Professor Tapir's book, appeared in France before Rudolf Wittkower's on the Italian Baroque, and his survey of the Roman field seems terribly thin. He underestimates the importance of realistic genre painting, and pays curiously little attention to the patrons of Poussin and his circle who have been studied in a number of extremely enlightening articles by Sir Anthony Blunt, Professor Pintard and others. He is far stronger on the situation in France, however, and his contribution to Czech history of the seven- teenth and early eighteenth centuries is the best that has yet appeared in English.

FRANCIS HASKELL

The Spore

Then We Fall. By Paul Ferris. (Hutchinson, 15s.) Flight into Camden. By David Storey. (Long- , mans, 16s.) Season of Adventure. By George Lamming. (Joseph, 21s.) Harvest on the Don. By Mikhail Sholokhov.

. (Putnam, 21s.) SOMETHING has been around which we all know and which could be described as a spore-like organism with rudimentary affections and a poor temper. Maintaining a tetchy adult adolescence, not believing much (understandably), and having a despair that it may deceive itself, this spore occasionally settles and may then dehisce into novels, criticism or drip-dry poems, before being bloWn off again into the mid-air of our provin- cial system. It dehisces into dislike; into detesta- tion of verbal, intellectual or emotional style. Its novels, understandably again, though perhaps. in

Some optimists contend that the dollar is intrinsically a very strong currency because there would be a balance of payments surplus if foreign aid and military spending were cut. But it is not practicable for the American Govern- ment at this hectic stage of the cold war suddenly to cut down this spending. If you are starving on a desert island with your best friend it is not an easy matter to cut him up in pieces and make him into soup. Of course, the American Trea- sury could allow much more gold to flow out: it could intervene effectively in the London bul- lion market. Its reserves, now down to $18,500 million, are still considerable. Of these some $11,000 million are required to meet the 25 per cent. gold ratio required for Federal Reserve bank notes and deposits, but this gold ratio can be waived by Act of Congress. However there are $15,000 million of foreign-held dollar de- posits and if these depositors got restive and desired to withdraw while American nationals were buying gold certificates abroad in large quantities, there could be such a heavy loss of gold that the Federal Reserve authorities would have to put an embargo on further sales at Fort Knox. At that moment the dollar price of .gold would soar and the dollar would be devalued de facto. This is only likely to occur at a time of panic if Mr. Kennedy were elected President pledged to a heavy spending programme.

COMPANY MEETING

Previous page

Previous page