CHESS

Deep end

Raymond Keene

Last Sunday the long-awaited clash took place between Gary Kasparov, the human world champion, and Deep Thought, the supreme chess computer. Kasparov played from the New York Academy of Arts in Greenwich Village, while DT beamed its moves via electronic link from its home base in Pittsburgh.

The general expectation was that Kas- parov would win, but the manner of his eventual victory must have been disturbing for the machine's programmers. Although DT can examine positions at the rate of 750,000 per second, Kasparov swiftly de- tected in his pre-game investigation of DT's earlier games that the metal mind was susceptible to strategic squeezes and tended to flounder in openings which were not a regular part of its repertoire. Indeed, the champion ruthlessly ex- ploited the insights he had gained into DT's prior body of games. The expert, playing through the two games which follow, will appreciate that there is no real clash of ideas, such as might occur in a game between two humans of reasonable strength, whatever the disparity in their ratings. Both of Kasparov's wins are in the nature of academic demonstrations, in which the computer is only given the chance to react. The helpless shuffling of White's king around the 29th move of the first game underscores this point. Kaspar- ov charitably predicted that Deep Thought would approach Grandmaster level within two to three years, but unless there is a huge improvement in strategic grasp, this remains optimistic. Further, as Deep Thought's games become more widely accessible, special preparation by Grand- master opponents will certainly make the machine's task that much more difficult.

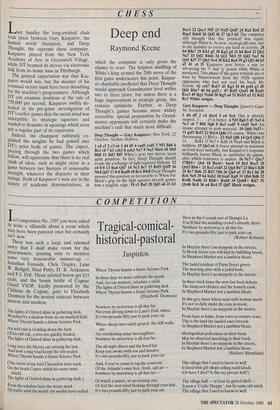

Deep Thought — Gary Kasparov: New York, 22 October; Sicilian Defence.

I e4 c5 2 c3 e6 3 d4 d5 4 exd5 exd5 5 Nf3 Bc16 6 Be3 c4 7 b3 cxb3 8 axb3 Ne7 9 Na3 Nbc6 10 Nb5 Bb8 11 Bd3 B15 White's next two moves seem quite pointless. In fact, Deep Thought should evade the exchange of light-squared bishops. 12 c4 0-0 13 Ra4 Qd7 14 Nc3 Bc7 15 BxfS Qxf5 16 Nh4 Qd7 17 0-0 Rad8 18 Rel RfeS Deep Thought assessed this position as favourable to White but Black's grip on the light squares already grants him a tangible edge. 19 c5 Ba5 20 Qd3 a6 21 h3 Bxc3 22 Qxc3 Nf5 23 NxfS Qxf5 24 Ra2 Re4 25 Rae2 Rde8 26 Qd2 f6 27 Qc3 hS The computer still thought that this position' was equal, although White is, by now, strategically lost, due to the inability to evolve any kind of activity. 28 b4 R8e7 29 Khl g5 30 Kg] g4 31 h4 Re4 32 Qb2 Na7 33 Qd2 R4e6 34 Qcl Nb5 35 Qd2 Na3 36 Qdl Kf7 37 Qb3 Nc4 38 Kh2 Re4 39 g3 Qf3 40 b5 a5 41 c6 f5 Kasparov now forces a win by advancing his T and `g' pawns while White is paralysed. This phase of the game reminds me of wins by Nimzowitsch from the 1920s against opponents who had not read his book My System. 42 cxb7 Rxb7 43 Kgl f4 44 gxf4 g3 45 Qdl Rbe7 46 b6 gxf2+ 47 Rxt2 Qxdl 48 Rxdl Rxe3 49 Rg2 Nxb6 50 Rg5 a4 51 RxhS a3 52 Rd2 Re2 White resigns.

Gary Kasparov — Deep Thought: Queen's Gam- bit Accepted.

1 d4 d5 2 c4 dxc4 3 e4 Nc6 This is already suspect. 3 . . . e5 is better. 4 Nf3 Bg4 5 d5 Ne5 6 Nc3 c6 7 Bf4 Ng6 8 Be3 cxd5 9 exd5 Ne5 An insane attempt to grab material. 10 Qd4 Nxf3+ 11 gxf3 Bxf3 12 Bxc4 Qd6 Of course, White was threatening 13 Bb5+ . 13 Nb5 Qf6 14 Qc5 Qb6 If 14 . . . Bxhl 15 Nc7+ Kd8 16 NxaS and Black is helpless. 15 Qa3 e6 A brave attempt to maintain an even keel tactically, but Kasparov's response brilliantly forces Black to surrender its queen, after which resistance is useless. 16 Nc7+ Qxc7 17BbS+ Qc6 18 Bxc6+ bxc6 19 Bc5 Bxc5 20 Qxf3 Bb4+ 21 Keg cxd5 22 Qg4 Bel 23 Rhcl Kf8 24 Rc7 Bd6 25 Rb7 Nf6 26 Qa4 a5 27 Rcl h6 28 Rc6 Ne8 29 b4 bxh2 30 bxa5 Kg8 31 Qb4 Bd6 32 Rxd6 Nxd6 33 Rb8+ RxbS 34 QxbS+ Kh7 35 Qxd6 Rc8 36 a4 Rc4 37 Qd7 Black resigns.

Previous page

Previous page