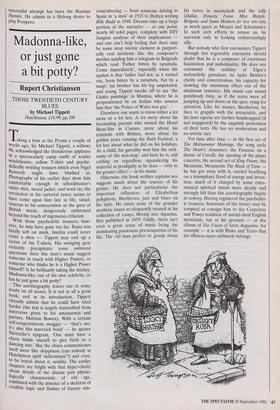

Madonna-like, or just gone a bit potty?

Rupert Christiansen

THOSE TWENTIETH CENTURY BLUES by Michael Tippett Hutchinson, £16.99, pp.290 Taking a bow at the Proms a couple of weeks ago, Sir Michael Tippett, a willowy 86, acknowledged the thunderous applause In a spectacularly camp outfit of scarlet windcheater, yellow T-shirt and psyche- delically swirling trousers which even Nigel Kennedy might have blushed at. Photographs of his earlier days show him comfortable enough in schoolmaster's white shirt, tweed jacket, and wool tie; the revolution in his sartorial tastes seems to have come upon him late in life, simul- taneous to his consecration as the guru of British music, dangerously enthroned beyond the reach of ingenuous criticism.

With those psychedelic trousers, how- ever, he may have gone too far. Raisa was fatally soft on mink, Imelda could never resist a shoe — Tippett may end up a victim of his T-shirts. His swinging gear certainly precipitates some awkward questions: does this man's music suggest someone in touch with Higher Powers, or someone who thinks he is a Higher Power himself? Is he brilliantly taking the mickey, Madonna-like, out of his own celebrity, or has he just gone a bit potty?

This autobiography leaves one in some doubt on all scores. It is not at all a good book, and in its introduction, Tippett virtually admits that he could have tried harder (the text is largely transcribed from interviews given to his amanuensis and partner, Meirion Bowen). With a certain self-congratulatory swagger — 'that's me; it's also this maverick book' — he quotes Nietzsche's epigram, 'One must have a chaos inside oneself to give birth to a dancing star.' But the chaos communicates itself more like sloppiness (can nobody at Hutchinson spell `millennium'?) and even, to be brutal about it, senility. The earlier chapters are bright with that hyper-clarity about details of the distant past physio- logically characteristic of old age, combined with the absence of a skeleton of credible logic and flashes of bizarre mis-

remembering — from someone driving to Spain in 'a mini' in 1933 to Britten writing Billy Budd in 1948. Dreams take up a large portion of the narrative — at one point, nearly 60 solid pages, complete with DIY Jungian analyses of their implications and one can't help feeling that there may be some stray oneiric element in purport- edly real incidents like the composer's mother sending him a telegram in Belgrade which read 'Father bitten by tarantula. Come immediately', especially when the upshot is that 'father had not, as it turned out, been bitten by a tarantula, but by a wasp', his brother has his leg amputated, and young Tippett sneaks off to see 'the Giotto paintings' in Mantua, where he is propositioned by an Italian who assures him that 'the Prince of Wales was gay'.

Elsewhere one wants to know either a lot more or a lot less. A lot more about his fascinating parents who owned the Hotel Beau-Site in Cannes, more about his relations with Britten, more about his golden years running the Bath Festival; a lot less about what he did on his holidays. As a child, his garrulity won him the nick- name of 'the non-stop', and here he is, still rattling on regardless, squandering his material as prodigally as he does — only to far greater effect — in his music. Otherwise, the book neither explains nor suggests much about the sources of his genius. He does not particularise the important influences of Elizabethan polyphony, Beethoven, jazz and blues on his style. He raises none of the grander aesthetic issues so eloquently treated in his collection of essays, Moving into Aquarius, first published in 1959. Oddly, there isn't even a great sense of music being the dominating passionate preoccupation of his life. The old man prefers to gossip about his tastes in marmalade and the telly (Dallas, Dynasty, Fame, Miss Marple, Bergerac and Some Mothers do 'ave 'em rate as much space as Mozart and Schumann). In such arch efforts to amuse us, he succeeds only in looking embarrassingly silly.

But nobody who first encounters Tippett through this regettable enterprise should doubt that he is a composer of enormous fascination and individuality. He does not command the nobility of Elgar's melancholy grandeur; he lacks Britten's clarity and concentration, his capacity for drawing the maximum effect out of the minimum resource. His music can sound pointlessly busy, as if the notes were all jumping up and down on the spot, vying for attention. Like his master, Beethoven, he likes to grapple with the intractable, and his later operas are further handicapped (if not scuppered) by the ungainly pretension of their texts. He has no moderation and no artistic tact.

Yet time after time — in the first act of The Midsummer Marriage, the song cycle The Heart's Assurance, the Fantasia on a theme of Corelli, the opening of the piano concerto, the second act of King Priam, the Messianic, Messiaenic The Mask of Time he has got away with it, carried headlong on a triumphant flood of energy and inven- tion, much of it charged by some extra- musical spiritual intent more deeply and strongly felt than this autobiography begins to convey. Having registered the psychedel- ic trousers, historians of the future may be tempted to consign him to the Carpenter and Powys tradition of sandal-shod English mysticism; but at his greatest — at the climax of The Vision of Saint Augustine, for example — it is with Blake and Yeats that his silliness more sublimely belongs.

Previous page

Previous page