PHILHARMONIC CONCERTS.

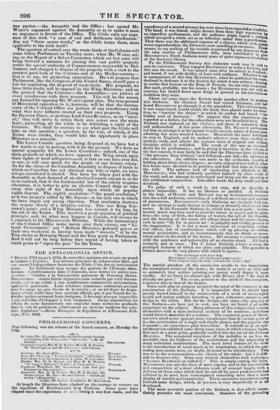

THE following was the scheme of the fourth concert, on Monday the 17th.

1141T 1.

Sh:fonia (No. 9). composed for the Philharmonic Society, terminating with Scurra.vn's " Ode to Joy "(As die Frende) RSETBOVIN. Principal Singers, Mrs. II. R. Manor, Miss M. 11.11AWNS, Mr. IIIIRSCMITI.r, 111111 Mr. PHI idirs ; with Chorus. ACT rt.

Oserture, Die Zaderflate Mozart'''. Song, Mr. Par I. I. tee, Yo Guardian Saints" (Palestine). I/ R.C1101CH Solo. Harp, from the Concerto in A minor. M. I.A11•ARK. 1:1111111.. 'Nett°, Mrs. 11. R. Bisons, and Miss AL B. HAVVV:9, " Ti veggor abbraciu" (II RaPo di Proserpina) WINTER Capriccio, Pianoforte. Mr. liosENIIAIN (has first per- formance in this country) ROSENH•111. Quartetio, Mrs. H. It. It isitoe, Miss M. B. HAWS,, Mr. IIORNCASTLIE, Mr. Paiu.iips. suit Chorus, " Alziam gli evriva" (Euryanthe) NV !BEL Leader, Mr. Lerma-Conductor, Mr. Mosclizr.Ks.

At length the Directors have plucked up the courage to venture on the repetition of BEETHOVEN'S long Sinfonia. Some years have elapsed since the experiment i mt..; rming it was first made, and the expediency of a second attempt has ever since been regarded as eoub The band, at was feared, might detract from their high repute' an imperfect performance, and the audience might regard a si°113 which occupied a whole act as an infliction rather than a gnoificn fill - Then there was the additional expense of a chorus, which, with ma mai"' never superabundant, the Directors were unwilling to encounter, causes, to say nothing of the trouble occasioned by any departure from e- the easy routine of Philharmonic bills, have contributed to BEETHOVEN'S Ninth Sinfonia many years of quiet repose on the sheriv-e-s of the Society's library. To the Philharmonic Society this elaborate work may be Ril to owe its existence. They engaged BEETHOVEN to write a , infimia and a this was the result. It was played soon after its arrival in Engl'nand; and heard, if not with dislike, at least with coldness. Whether it w in consequence of this that BEETHOVEN, when he published the se:, declined to dedicate it to the Society for which it was written, choosing' to confer that honour on the King of Prussia, we can only conjecture-- But such, probably, was his reason ; for BEETHOVEN was not only Do. courtier, but looked down upon kings in general as his inferiors doubtless they were. About ten years since, the Society made another effort to produce this Sinfonia. Sir GEORGE SMART had visited Germany, and hag heard BEETHOVEN go through it at the pianoforte. This circumstance it was conjectured, would enable the band, then placed under his diree: non, to "untwist the chains" in which its author had bound male hidden soul of harniony." We suppose that the experiment was regarded as a failure, for the subscribers were not benefited by it. The Sinfonia was replaced on the shelves ; and there it remained, dusty and undisturbed. A few years afterwards, Mr. NEATE'S enthusiasm led him to attempt it at his annual benefit concert, where it found some admiring but more wearied hearers. Meanwhile the score bud found its way to England; and its author's admirers were thus madded to analyze, study, and admire the copious store of original and striking thoughts which it unfolded. The result of this was an increased desire for its performance ; and in giving it insertion in the gieme of the last concert, it may fairly be said that the Directors have yielded to "the pressure from without," and followed—not led—the opinions of the subscribers. An addition was made to the orchestra, capable of holding about forty chorus-singers ; an extra rehearsal was called, when five hours were devoted to its practice, and half that time on Saturday the 15th. The arduous task of conducting was allotted to Mr. MoscitELEs ; who had evidently qualified himself by close study of the score, and an attempt to understand and bring out the meaning of this celebrated composition. Into abler hands the duty could iiot have devolved.

To judge of such a work is not easy, and to describe it almost impossible. It has no likeness or parallel. A Sitifonie in the time of HAYDN and MOZART was an instrumental composi- tion for a full orchestra, consisting of a defined succession and number of movements. BEETHOVEN'S early Sinfonias are similarly laid out, and no attempt is made therein to enlarge or diversify their usual cha- racter. In his Pastorale Sinfonia he struck into a new path : instru- mental music was here used to describe nature in repose and in agita- tion—the song of birds, the falling of waters, the roll of the thunder, and the howling of the storm, the village dance and the rustic ehorus, each in turn "by his so potent art" is palpably and vividly present to the imagination. It is not a mere succession of surprising (aches. trill effects, but of combinations which call up pleasing or sublime mental associations, and so instantaneously that no doubt or uncer- tainty exists in the mind of the hearer. His meaning is communicated with the quickness and universality of an electric shock. All feel it

instantly and at once. The C minor Sinfonia relates a story, the principal features of which are plain and palpable. The gauntlet is thrown down in the very phrase with which it opens- " The challenger with fierce defy Iii, trumpet sounds: the challenged makes reply : with clangour rings the field, resounds the vaulted sky."

The martial grandeur of the conclusion recalls to the imagination the triumphant return of the victor ; its strain is at once so lofty and so animated, that neither painting nor poetry could depict it more vividly. As we listen we almost sigh, with BURKE, that 4, the days of chivalry are gone." The scene, present to the mind of the composer, is present also to that of the hearer. Some such plan or purpose occupied the mind of BEETHOVFN in the construction of this Sinfonia. It is impossible that he should have merely busied himself in the construction of a work of unexciinpled length and variety without intending to give coherence, meaniog, and design to the whole. But for the design—the story—the purpose of this Sinfonia—we have yet to seek, nor have we heard a plausible conjecture on the subject. Many admirers of this composition content themselves with a mere technical analysis of its contents ; and these would furnish materials for a volume. The expansive power of BEET110VEN'S mind never appears more conspicuous than in various parts of it—the germination of a single and simple phrase, and the gigantic size it assumes, arc sometimes quite marvellous. It reminds us of an opti- cal deception exhibited some thirty years since, in which a human figure, first seen as a mere point, gradually swelled into the size of the Farnese Hercules. The occasional sweetness of the melodies is no less re- markable than the boldness of the modulations and the originality of many orchestral combinations. The most novel feature of the work is the introduction of vocal music at its termination, to which the pre- ceding movements were, no doubt, designed to be introductory. This was to he time consummation—the climax of the whole : but t it sdi cult to discover why. Some may content themselves with replying-. " because Beethoven so willed it." This is simply cutting the knot. BEETHOVEN was not the slave of mere caprice, and in the con.structioa and composition of a most elaborate work of unusual length, with a defiance of those rules which both he and all his great predecessors had adhered to, he must have contemplated something more than a mere display of novelty and eccentricity. These successive movemeuts carry forward some design, which, at present, is very imperfectly It at alt developed.

The most eccentric portion of the Sinfonia is that which imme- diately precedes the vocal conclusion. Snatches of the preceding

movements are heard in succession, while the violoncellos are playing st intervals -recitative passages. This part bears some affinity to his celebrated pianoforte piece, " The Birth of Melody." The same discordant elements seem striving to mould themselves into form. DRYDEN, here, is the composer's best expositor-. n When Nature underneath a heap Of jarring atoms lay,

And could not heave her head,

The town), voice was heard from high,

Arise, ye more than dead.

Then hot awl cold and moist and dry In order totheir ,.tai ions leap.

And Muele's power obey."

Out of the instrumental contention we have described, there arises a quiet and unpretending melody, beaunfullyccrtrasting itself with the uncouth phrases that had preceded it ; which the bass voice, after a short recitative, adopts; and It becomes at once the prelude mid founda- tion to the conclusion of the Sinfonm. The same idea floats along through a combination of voices and instruments with all the profuse variety which BEETHOVEN had so completely at command. Here his purpose o is clear and intelligible ; the poet and the musician mutually s aid and illustrate each other. The poet is SCHILLER ; and the words are part of his Ode to Joy, which is often sung in verse and chorus by the students of the German Universities over their cups. The melody which they are accustomed to use, though simple as that of BEET- UOVEN, bears no other resemblance to it. The instrumental harmonics with which he has enriched his own motivo are exquisitely beautiful ; but the conclusion of the Sinfonia, regarded us a piece of vocal writing, is open to censare,—that is, if we are to regard voices as the principal

i elements of a composition n which they are engaged. Here they tip.

peered merely to add something (not much) to the instrumental effect. Some of the passages are uncouth and shapeless, and the tenor solo is destitute of any vocal attribute or character. If 13EETHOVEN is right in this employment of vocal power, every other great writer must have been wrong. Some allowance must be made for the imperfect way in which the chorus was sung, and for the inability of forty unpractised singers to contend with the roar of the Philharmonic orchestra: but this cannot be pleaded in behalf of the principal voice parts, which, though correctly sung, produced, as on former trials, no pleasing or satisfactory effect.

Of the instrumental part of the performance it would be difficult to

speak in terms of exaggerated praise, considered almost as a first at- tempt. Repeated efforts will be necessary to develop all the beauties of such a work ; and these, no doubt, will he applied, for its success was such as to secure its annual repetition. There is still great diversity of opinion about his merits, not among the unlearned, but among the most competent judges. According to some, it leaves all similar com- positions even of the same author at a great distance ; while others re- gard it as wild and incomprehensible, though occasionally gleaming with beauty. We are by no means of the former opinion. Masterly as this composition is, we are not disposed to give it a higher rank than some others of the same author ; and the pleasure which results from its performance is, at present, less. Their plan and purpose is clear and intelligible, and it is not yet so with this. With sonic hearers it is "owe igsiotuan pro magnifica :" the deeper the mystery, the more pro- found is their admiration—the more unintelligible, the more vehement their applause—just us a good Catholic asserts his belief of the doc- trine of the real presence with fonder protestations than the simplest truths of natural or revealed religion. We are nut, as yet, converts to this faith.

It was anticipated that the second act of the concerts would have

been "flat and unprofitable." Such, however, was not the case. The Overture to Die Zinibevi,ve was encored, and even WINTER'S Duet found favour with the audience. LARAMIE'S Solo ought not to have been suffered : the compositions of such a writer as HUMMEL ought not to be mutilated and perverted to please the caprice of any per- former; and at the Philharmonic Concerts such practice is, most pro- perly, forbidden by the laws of the Society. By what sinister influ- ence did M. LABAREE obtain their violation?

Previous page

Previous page