Notebook

When SouthAfrica surveys its opponents, it must enjoy feelings of considerable complacency. Why should it be tempted to reform itself, or change its ways in the smallest degree, when its enemies are themselves so lacking in virtue? Angola, for example, is in the forefront of the campaign for free elections in Namibia and the withdrawal of foreign — that is to say, South African — troops from that country. Yet Angola has never held the free elections that it was pledged upon independence to hold, and it harbours many thousands of Cuban soldiers and East German advisers who show not the slightest sign of going away. And any guilt that South Africans may feel about apartheid must be somewhat assuaged by the spectacle of the anti-Springbok rioters in New Zealand who, it would appear, are being manipulated by a ragbag of political extremists. It is very sad to see New Zealand, of all places, in the throes of street violence. It is even sadder that the pretext for the violence should be the game of rugby which, in New Zealand, has the status of a religion. If New Zealand is no longer to be a haven of peace, and if its rugby team, as may well happen, is to join that of South Africa on the interna tional blacklist, it is rather hard to see what the point of the country will be.

C ome months ago I put forward the L.3 theory that China was seeking to undermine the morale of the West by sending us sterile pandas. In what appeared on the face of it to be gestures of friendship, the Chinese government in the early Seventies presented pairs of pandas to both Mr Heath and Mr Nixon, thereby exciting expectations that they would breed. Enormous trouble and large sums of money were lavished on efforts to achieve this result, but always without success. Might it not all have been an elaborate Chinese joke at the expense of these two unattractive Western statesmen? It now appears that I was wrong, for one of Mr Heath's pandas, Ching Ching, is expected to give birth any minute. The pregnancy was achieved by artificial insemination, which made me wonder why this technique has not been tried before, given the extraordinary reluctance of pandas to mate. An official of London Zoo explained to me, however, that artificial insemination is not nearly as easy as it sounds, and that the techniques for carrying it out successfully in the case of pandas have only recently been acquired. The Zoo is very over-excited about the whole thing, anticipating a huge increase in its income from visitors when the cub is born. Sentimentalists should be warned, however, not to rush to see the cub at once, because for the first few days of their lives pandas are not cuddly at all, but blind, hairless and perfectly disgusting. Talking of sentimentalists, Mr Norman St John Stevas is one. Great Britain, he believes, is 'a generous and charitable country' which displays most strongly 'the natural virtues of care and concern for our fellow men'. Uniquely fitted to reflect these aspects of the national character is, he says, the Tory Party, 'with its unequalled tradition of social reform, its sensitive appreciation of the needs of the people, its rejection of a society stigmatised by extremes of wealth and poverty . . . ' Mrs Thatcher, too, is not the 'flint-faced, uncaring woman' that her enemies make her out to be, but has the qualities, if she chooses to use them, to draw the party together 'within broad and tolerant parameters'. This was the burden of a letter he wrote to the Daily Telegraph this week. But it strains the imagination to see either the modern Tory Party or modern Britain in such a comforting light. To claim for the Conservative Party as its distinguishing characteristics the virtues of compassion and sensitivity seems to me to be slightly barmy. And, whether or not Mrs Thatcher has the qualities to provide the sort of leadership that Mr St John Stevas would like, he should remember why she was elected to office in the first place. It was because she offered, in contrast to her predecessors, the hope of a government that would eschew empty 'compassion' and weak-minded 'tolerance', but actually try with honesty to address itself to our problems. Perhaps nothing but sentimentality now stands between Norman and the SDP. The time has probably come to abolish the BBC's Dimbleby lectures. Lectures do not make good television anyway, and now that the BBC's Governors have decided to reserve for themselves the choice of lecturer, we may expect the Dimbleby lectures to become more boring still. The BBC's self-confessed 'series of cock-ups' over the organisation of this year's lecture — the teasing of men like Professor E.P. Thompson and Mr Heath with halfinvitations subsequently withdrawn — have reduced it to a farce, and not therefore a suitable memorial to Richard Dimbleby. Another consequence has been to provide Professor Thompson with more publicity for his anti-nuclear propaganda than he could have hoped for it his lecture had gone ahead.

Readers who are mystified by the modern techniques of magazine production might like to know how I spent the morning of press day this week. I arrived early in the office to find that Christopher Booker's article on Macmillan and the Cossacks, which had supposedly been put through the letter-box late the previous night, was nowhere to be found. After searching everywhere without success, I ended up going through the plastic sacks of rubbish in the area until finally I found the article, wet and smeared under a pile of coffee grounds. The cleaners had come during the night and decided, presumably, that it was unsuitable for publication. That is why I am writing this Notebook with slimey fingers and am not in the best of tempers. Mr Booker's article was also rather longer than expected, which explains why the subscription coupon appears this week on page three. All of which is an excuse for me to urge all casual buyers of this paper to fill in the coupon and send it off with their cheques.

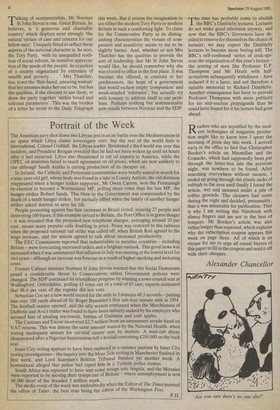

Alexander Chancellor

Previous page

Previous page