`I'VE EATEN AN OYSTER-CATCHER'

Simon Courtauld interviews

Viscount Massereene and Ferrard, one of Britain's most endearing eccentrics

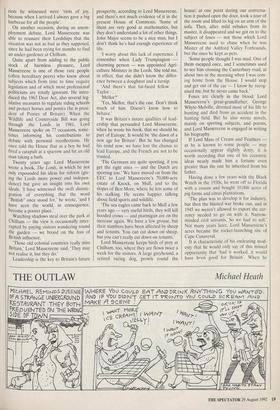

AS ANOTHER shooting season gets under way, a rare game bird is about to re- emerge. It is the Viscount Massereene and Ferrard, veteran field sportsman of 78 sea- sons, who broke his leg last Christmas and has since been kept away from his favourite habitat, the House of Lords. But he will be back after the summer recess.

Eight years ago, during debate on the Wildlife (Northern Ireland) Order in the House of Lords, Lord Massereene was talking about shooting curlew. They were not worth eating, he said, and the only reason he could think of for not giving them protection was to give Irishmen the chance to shoot something other than each other. Earlier this month, sitting in the window of his drawing-room at Chil- ham Castle, Kent, and looking over the gloriously unspoilt Stour valley, Lord Massereene confirmed to me that he had once eaten a curlew, and it was pretty unpleasant. He went on, 'I've eaten an oyster-catcher, too, and that was even worse.' `Why did you eat an oyster-catcher?'

`Because I shot one by mistake, towards dusk, thinking it was something else. So I thought I might as well see what it was like to eat. Very fishy. You don't see as many of them about these days.'

John Clotworthy Talbot Foster Whyte- Melville Skeffington, 13th Viscount Massereene and 6th Viscount Ferrard, is experienced in the ways both of wildlife and of the Irish. In 1922, on his eighth birthday, the family house, Antrim Castle, was sacked and burnt by Sinn Feiners.

`Lloyd George had asked my father to disband his guards in return for police pro- tection. My father agreed, but Lloyd George broke his word. I remember being led along the roof and told to get down because of the shooting.'

There was another Irish family seat, Oriel Temple in County Louth, now a Cis- tercian abbey, and Lord Massereene keeps the Irish titles of Baron Oriel and Baron of Loughneagh. He is also Deputy Lieutenant of Antrim, but most of his time is divided between Kent, his estate on the Isle of Mull and the House of Lords.

Chilham is a large Jacobean house, built by Inigo Jones on the site of a Norman cas- tle. It was a blessed relief to come in from the heat of the day to the cool of stone- flagged floors and thick, panelled walls. Lord Massereene kept his tweed jacket on. He is small-framed and still looks fit after years of country exercise, not to mention his early days as amateur rider and racing driver — he drove the leading British car in the 1937 Le Mans Grand Prix. He speaks slowly, having suffered from a stammer in his youth, and, perhaps surprisingly, has a rather gentle voice.

Lord Massereene made his distinctive mark on the House of Lords more than 30 years ago, prompting Lord Hailsham once to observe, when he was Lord Chancellor, that while the Upper House might need some reforming, he hoped that Lord Massereene would never be reformed. During a debate on the Brixton riots in the early 1980s, Lord Massereene offered the comment that he was 'the only member who has spoken today who has had agricul- tural estates in Jamaica', where the only

riots he witnessed were 'riots of joy, because when I arrived I always gave a big barbecue for all the people'.

On another occasion, during an unem- ployment debate, Lord Massereene was able to reassure their Lordships that the situation was not as bad as they supposed, since he had been trying for months to find an under-gardener at Chilham.

Quite apart from adding to the public stock of harmless pleasure, Lord Massereene is one of those rare people (often hereditary peers) who know about subjects which from time to time require legislation and of which most professional politicians are totally ignorant. He intro- duced the 1963 Deer Act, also several leg- islative measures to regulate riding schools and protect horses and ponies (he is presi- dent of Ponies of Britain). When the Wildlife and Countryside Bill was going through the Lords in 1981, Lord Massereene spoke on 77 occasions, some- times informing his contributions to debate with personal recollections. He once told the House that as a boy he had fired a catapult at a sparrow and hit an old man taking a bath.

Twenty years ago Lord Massereene wrote a book, The Lords, in which he not only expounded his ideas for reform (giv- ing the Lords more power and indepen- dence) but gave an insight into his own ideals. 'I have witnessed the swift disinte- gration of everything that the word "British" once stood for,' he wrote, 'and I have seen the world, in consequence, become a poorer place.'

Watching shadows steal over the park at Chilham — the view is occasionally inter- rupted by paying visitors wandering round the garden — we brood on the loss of British influence.

'Those old colonial countries really miss Britain,' Lord Massereene said. 'They may not realise it, but they do.'

Leadership is the key to Britain's future prosperity, according to Lord Massereene, and there's not much evidence of it in the present House of Commons. 'Some of them are very good at mathematics, but they don't understand a lot of other things. John Major seems to be a nice man, but I don't think he's had enough experience of life.

'I worry about this lack of experience. I remember when Lady Trumpington charming person — was appointed Agri- culture Minister in the Lords. She told me, in effect, that she didn't know the differ- ence between a doughnut and a turnip.

'And there's that fat-faced fellow . . . Taylor ... '

'Mellor?'

'Yes, Mellor, that's the one. Don't think much of him. Doesn't know how to behave.'

It was Britain's innate qualities of lead- ership that persuaded Lord Massereene, when he wrote his book, that we should be part of Europe. It would be 'the dawn of a new age for Britain'. But he has changed his mind now: we have lost the chance to lead Europe, and the French are not to be trusted.

'The Germans are quite sporting, if you get the right ones — and the Dutch are sporting too.' We have moved on from the EEC to Lord Massereene's 70,000-acre estate of Knock, on Mull, and to the slopes of Ben More, where he lets some of his stalking. He seems happier talking about field sports and wildlife.

'The sea eagles came back to Mull a few years ago — very useful birds, they will kill hooded crows — and ptarmigan are on the increase again. We have a few grouse, but their numbers have been affected by sheep and tenants. You can cut down on sheep, but you can't really cut down on tenants.'

Lord Massereene keeps birds of prey at Chilham, too, where they are flown twice a week for the visitors. A large greyhound, a retired racing dog, prowls round the house; at one point during our conversa- tion it pushed open the door, took a tour of the room and lifted its leg on an arm of the sofa. Then, after mild rebukes from its master, it disappeared and we got on to the subject of foxes — not those which Lord Massereene used to chase when he was Master of the Ashford Valley Foxhounds, but the ones he kept as pets.

'Some people thought I was mad. One of them escaped once, and I sometimes used to see him crossing the Canterbury road, at about two in the morning when I was com- ing home from the House. I would stop and get out of the car — I know he recog- nised me, but he never came back.'

Foxes are clearly in the blood: Lord Massereene's great-grandfather, George Whyte-Melville, devoted most of his life to hunting and died from an accident in the hunting field. But he also wrote novels, mainly on sporting subjects, and poems, and Lord Massereene is engaged in writing his biography.

If Lord Mass of Cream and Feathers as he is known to some people — may occasionally appear slightly dotty, it is worth recording that one of his eccentric ideas nearly made him a fortune even greater than the one he inherited from his father.

Having done a few years with the Black Watch in the 1930s, he went off to Florida with a cousin and bought 10,000 acres of pig farms and citrus plantations.

'The plan was to develop it for industry, but then the blasted war broke out, and in 1945 we weren't allowed to export the cur- rency needed to go on with it. Narrow- minded civil servants. So we had to sell.' Not many years later, Lord Massereene's acres became the rocket-launching site of Cape Canaveral.

It is characteristic of his endearing mod- esty that he would only say of this missed opportunity that 'had it worked, it would have been good for Britain'. When he returns to the House of Lords in October, he will be, as he puts it, 'speaking up for Britain'.

It is his idea of Britain, of course, which may not appeal to everyone. But in these depressed times it is comforting to know that the Viscount Massereene and Ferrard is still going strong.

Previous page

Previous page