BOOKS

Return of the monarch

Blair Worden

THE SIX WIVES OF HENRY VIII by Antonia Fraser Weidenfeld and Nicholson, f20, pp. 458 It is a surprise to realise that Antonia Fraser has not written about Henry VIII's wives already. She has written so many books on monarchs and women. There are her long biographies of Mary Queen of Scots and Oliver Cromwell and Charles II. There is The Weaker Vessel, a long study of 17th-century women. There is The Warrior Queens, an account of women leaders from Boadicea to Margaret Thatcher which, exceptionally among her history books, she kept below 400 pages. There is a novel about a royal wedding. Then there is Wei- denfeld's 'Kings and Queens of England' series, which she edited and to which she contributed a life of James I. Yet, she tells us, it took a friend to suggest the subject of Henry VIII's consorts, with the words, This may not sound like a good idea, but...'

It could be a good idea. Kings and queens are back in historical business, after the decades when they seemed to have been mere puppets of social and economic forces, and when interest in them seemed a frivolous distraction from serious issues of class and ideology. So long as the civil wars of the mid-17th century appeared to have been caused by the rise of the gentry or of the bourgeoisie, the shortcomings of Charles I seemed to have been at most the trigger of the conflict. Now that social and economic explanations of the wars have collapsed, Charles's character looks once more to have been at the heart of the prob- lem.

The same pattern is observable in accounts of the break with Rome. So long as the Reformation was regarded as an explosion of popular and progressive senti- ment, Henry VIII's matrimonial problems seemed merely to have affected its timetable. Now that we know how deeply entrenched was the old religion and how little iupport there was for the new, we remember that the Reformation was an act of state, and realise that England might well have remained a Catholic country but for Henry's roving eye and his need for a male heir.

The return to a Court-centred history is something more than a rediscovery of the effects of Cleopatra's nose, or of Anne Boleyn's black eyes. Historians, increasing- ly drawn to the relationship between politi- cal power and visual or literary statements, have seen that the rituals and entertain- ments of the Renaissance Court, its elabo- rate masques and chivalric displays, can help us to reconstruct not merely the Power struggles of Tudor England but its Political and social values.

If these and other historiographical developments have largely passed Fraser by, it is hard to blame her. Specialist histo- rians write for each other. I say 'specialist' rather than 'professional', for the term `professional historian' has come, by a sleight of hand convenient to those who recognise themselves in the term, to con- flate two qualities: the quality of having scholarly standards, and the quality of earning a salary.

Fraser's scholarship, albeit unambitious, is always diligent, clear-headed, responsi- ble.Even so, salaried history has made her kind hard to write. Fraser is the 20th centu- ry's equivalent to the popular Victorian writer Agnes Strickland. Like Fraser, Strickland came from a versatile literary family; like Fraser, she was devoted to Mary Queen of Scots; and like her she wrote lives of the queens of England. Strickland, with few predecessors to guide her and few salaried historians to look over her shoulder, made errors of scholarship and judgement which Fraser would not commit. Yet, for the same reason, she was able to carve out fresh historical territory. Fraser can travel only where learned arti- cles have been before her.

She has a high respect for Henry's long- suffering wives, most of them women of intellect and strength of character. She wants to banish the clichés: 'The Betrayed Wife' (Catherine of Aragon), 'The Temptress' (Anne Boleyn), 'The Good Woman' (Jane Seymour), 'The Ugly Sister' (Anne or Anna or Cleves), 'The Bad Girl' (Katherine Howard), and 'The Mother Fig- ure' (Catherine Parr). All her characterisa- tions are shrewd and sympathetic and, as far as they go, persuasive. But none of them is three-dimensional There are two problems, one of style, one of content. Fraser's books evidently sell in large numbers, and if those who buy them read them, and thus learn about a past that would otherwise remain closed to them, she is performing a valuable service. But do they read them? Can they really get through so many pages of nerveless prose? `On the Welsh borders that spring, the weather was notably cold and wet, as a result of which sickness of various kinds was rife.' It is one thing to pen a sentence like that in a tired moment, another not to tear it up next day.

Solecisms jostle with limp constructions. Of Henry's final parting with Catherine of Aragon we learn that 'Unlike his behaviour towards Wolsey, he did not bid her an affa- ble - if false - farewell.' At Anne Boleyn's coronation 'the celebrations of the City were not an unalloyed success at the grass roots level such things were supposed to reach.' Catherine Parr, nursing Henry, `moved into a small bedroom next to his, out of her queenly apartments, emphasis- ing the fact that a man on his sixth wife must be assumed to stand in need of a nurse and for this role the widowed Lady Latimer' - Catherine herself - 'was well equipped.' Perhaps Fraser's prose would be sprightlier if her grasp of historical context were stronger. In Mary Oueen of Scots, much the best of her books, it was strong. Here she is unable to bring alive the politi- cal and religious conflicts to which the fate of Henry's queens belonged, and which would give the book a spine. Without that context the reader's interest is unlikely to be sustained, unless by pity for blighted lives or by interest in the clothes or the jewels or the sex.

The result, far beneath Fraser's hon- ourable aim, is a sort of slow-moving Tudor Dallas. Henry. VIII is 'lithe and golden- haired' in his youth, when 'a vast love of life in all its forms exuded from him'. In time he is captured by the 'tempestuous, challenging Anne Boleyn'. Anne's outfit for her coronation is 'a mixture of the virginal and the resplendent'. For her execution she favours 'a mantle of ermine over a loose gown of dark grey damask, trimmed with fur, and a crimson petticoat'. In Catherine Parr, who 'comes across as someone who enjoyed the small pleasures of life', 'shoes were a real passion'.

The divorcees, Catherine of Aragon and Anne of Cleves, linger at the ranch. Anne of Cleves takes to drink. There are beauties and fast women. Lady Margaret Douglas is `the best-looking Tudor girl of her genera- tion'. The 'Bad Girl', Katherine Howard, proves to be merely a Good Time Girl, but, being 'the sort of girl who lost her head easily over a man', she commits infidelities which 'tick away like a time-bomb'.

In a shorter, tauter book the limits of Fraser's vision would matter less. The Six Wives of Henry VIII is dedicated to Harold Pinter, whose plays reduce experi- ence to the smallest number of words in which it can be communicated. Fraser seems to work on an opposite principle. She needs a word-limit.

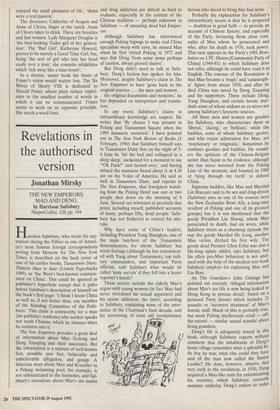

Previous page

Previous page