CHESS

Encore Agincourt

Raymond Keene

Two things are determining ineluctably that tournament chess must speed up, probably to the point where all games must be finished in one session, without the possibility of adjournment.

These are, first, the exigences of tourna- ment reporting, which means that ad- journed games simply make the results a nonsense for the public. If many games are unfinished at the end of a round it is too difficult to follow the tournament sequ- ence. Far more importantly, though, the wide accessibility of computers means that no game can any longer be safely ad- journed without one side or the other justifiably fearing hostile intervention by microchip-generated analysis. If tourna- ment chess is to be played between humans it must be seen to be that way, therefore adjournments will be phased out, gradual- ly, even up to world championship level.

A recent team competition in France showed an ideal solution to this. Top teams of four from England, the USA, Holland and France competed for a £6,000 first prize, but with every game having to be completed in the grand total of two hours. This is ample time to produce excellent chess and, indeed, international rules even permit games played at such a time limit to be officially rated, though in this case I believe that they were not. The outcome was some excellent chess and a superb triumph for the English team which domin- ated its rivals and reasserted our position as world number two, second only to the Russians. Here is a game from our fourth- round 4-0 whitewash of the French.

I was less happy with a comparable speed tournament in Monaco, where Ivan- Cannes Team Tournament

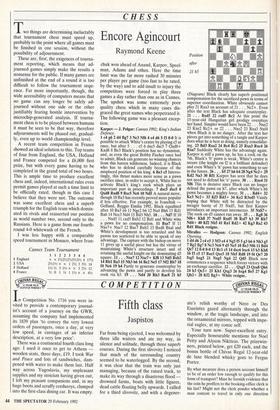

1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 1 England

x x 11/22%2%3%3% 4 171/2 2 USA 21/211/2 x X 1 21/2 3 3% 14 3 Holland 1½½ 3 11/2 x x 32½ 12

4 France

1/2 0 1 1/2 1 11/2 x x 41/2

chuk won ahead of Anand, Karpov, Speel- man, Adams and othes. Here the time limit was the far more rushed 30 minutes per player per game (too fast to be rated, by the way) and to add insult to injury the competitors were forced to play three games a day rather than one as in Cannes.

The upshot was some extremely poor quality chess which in many cases dis- graced the great names who perpetrated it. The following game was a pleasant excep- tion.

Karpov —J. Polgar: Cannes 1992; King's Indian Defence. 1 c4 g6 2 d4 Bg7 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 e4 d6 5 f3 0-0 It is possible to attack White's centre by playing c5 at once, but after 5 . . . c5 6 dxc5 dxc5 7 Qxd8+ 1Cxd8 8 Be3 Black's position has no dynamism, and, as even the great Bobby Fischer once had to admit, Black can generate no winning chances from this barren wilderness. Indeed, it is Black who has to defend carefully because of the misplaced position of his king. 6 Be3 c5 Interes- tingly, this thrust makes more sense as a pawn sacrifice since, in order to accept it, White has to activate Black's king's rook which plays an important part in proceedings. 7 dxc5 dxc5 8 Qxd8 Rxd8 9 Bxc5 Nc6 10 Nd5 A natural move, though 10 Ba3 has recently proved more popular if less effective. For example, in Ivanchuk — Gelfand, Reggio Emilia 1992, Black equalised after 10 Ba3 e6 11 Nge2 b6 12 Na4 Bh6 13 Rdl Ba6 14 Nec3 Nd4 15 Bd3 Nh5. 10. . . Nd7 If 10 . . . Nxd5 11 cxd5 Bxb2 12 Rdl and White wins a pawn for no compensation. 11 Bxe7 If 11 Nxe7 + Nxe7 12 Bxe7 Bxb2 13 Bxd8 Bxal and White's development is too retarded and his pawns too scattered to be able to speak of any advantage. The capture with the bishop on move 11 gives up a useful piece but has the virtue of maintaining White's structure intact and of retaining the useful knight on the dominating d5 square. 11. . . Nxe7 12 Nxe7+ K18 13 Nd5 Bxb2 14 Rbl Ba3 15 Nh3 b6 16 Be2 Ne5 17 Nf2 Bb7 18 f4 Nc6 19 h4 Partly to generate counterplay by advancing the pawn and partly to develop his rook via h3. 19 . . . Nd4 20 Rh3 Rac8 21 h5 Position after 21 h5 (Diagram) Black clearly has superb positional compensation for the sacrificed pawn in terms of superior coordination. White obviously cannot play 21 Rxa3 on account of 21 . . . Nc2+. Even after the text Black has adequate counterplay. 21 . . . Bxd5 22 cxd5 Rc2 At this point the 15-year-old Hungarian girl prodigy overplays her hand. Simpler would have been 22. . . Nxe2 23 K:ce2 Rc2+ or 22 . . . Nxe2 23 Rxa3 Nxf4 when Black is in no danger. After the text her pieces get into something of a tangle and Karpov does what he is best at doing, namely consolidat- ing. 23 Bd3 Itxa2 24 Bc4 Rc2 25 Rxa3 Rxc4 26 Rxa7 Suddenly White has the advantage again. Karpov is still a pawn up, he has a rook on the 7th, Black's 'b' pawn is weak, White's centre is secure (the knight on f2 is a brilliant defender) and even White's 'h' pawn has something to say in the future. 26. . . b5 27 h6 b4 28 Ng4 Nc2+ 29 Kd2 Na3 30 Rfl Karpov has seen that he does not need to defend his `e' pawn. 30. . . Rxe4 31 Nf6 This is decisive since Black can no longer defend the pawn on h7, after which White's h6 pawn becomes a mighty force. 31 . . . Rd4+ 32 Ke3 Nc2+ 33 Kf3 Rd3+ 34 Ke2 R3xd5 Vainly hoping that White will be distracted by the meagre booty of 35 Nxd5, but first Karpov introduces an important intermezzo. 35 Nxh7+ The rook on d5 cannot run away. 35. . . Kg8 36 N16+ KM 37 Nxd5 Rxd5 38 Rxf7 b3 39 Rb7 Nd4+ 40 Kf2 Nb5 41 Ral Rd2+ 42 Kg3 Ra2 43 Rdl Black resigns.

Miralles — Hodgson: Cannes 1992; English Opening. 1 d4 d6 2 c4 e5 3 Nf3 e4 4 Ng5 f5 5 g3 h6 6 Nh3 g5 7 Bg2 Bg7 8 Nc3 Nc6 9 d5 Ne5 10 Be3 Nf6 11 0d4 Qe7 12 0-0 0-0 13 Rd c5 14 dxc6 bxc6 15 b3 Kh8 16 f3 c5 17 Bxe5 Qxe5 18 Nb5 Rd8 19 f4 Qe7 20 fxg5 hxg5 21 Nxg5 Ng4 22 Qd5 Black now commences a sequence which forces victory with an exchange sacrifice. 22. . . Qxg5 23 Qza8 Qh6 24 h3 Qe3+ 25 Khl Qxg3 26 hxg4 Be5 27 Kgl Qh2+ 28 Kf2 Bg3+ White resigns.

Previous page

Previous page