TRAVEL

Chasing the tiger

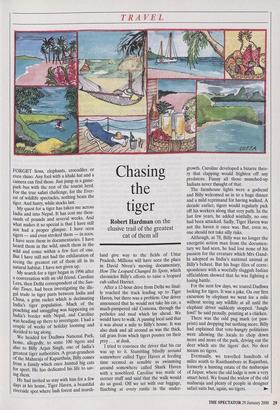

Robert Hardman on the elusive trail of the greatest cat of them all FORGET lions, elephants, crocodiles or even rhino. Any fool with a khaki hat and a camera can find those. Just jump in a game- park bus with the rest of the tourist herd. For the true safari challenge, for the Ever- est of wildlife spectacles, nothing beats the tiger. And hurry, while stocks last. My quest for a tiger has taken me across India and into Nepal. It has cost me thou- sands of pounds and several weeks. And what makes it so special is that I have still not had a proper glimpse. I have seen tigers — and even stroked them — in zoos. I have seen them in documentaries. I have heard them in the wild, smelt them in the wild and come within a few feet of one. But I have still not had the exhilaration of seeing the greatest cat of them all in its natural habitat. I have not given up. My search for a tiger began in 1996 after a conversation with an old friend. Caroline Lees, then Delhi correspondent of the Sun- day Times, had been investigating the ille- gal. trade in tiger parts between India and China, a grim racket which is decimating India's tiger population. Much of the Poaching and smuggling was happening on India's border with Nepal, and Caroline was heading up there to investigate. I had a couple of weeks of holiday looming and decided to tag along. We headed for Dudhwa National Park, home, allegedly, to some 100 tigers and also to Billy Arjan Singh, one of India's greatest tiger authorities. A great-grandson of the Maharaja of ICapurthala, Billy comes from a family which once hunted big cats for sport. He has dedicated his life to sav- ing them.

He had invited us stay with him for a few days at his home, Tiger Haven, a beautiful riverside spot where lush forest and marsh- land give way to the fields of Uttar Pradesh. Millions will have seen the place in David Niven's moving documentary, How The Leopard Changed Its Spots, which chronicles Billy's efforts to raise a leopard cub called Harriet.

After a 12-hour drive from Delhi we final- ly reached the track leading up to Tiger Haven, but there was a problem. Our driver announced that he would not take his car, a much-pampered old Contessa, through the potholes and mud which lay ahead. We would have to walk. A passing local said that it was about a mile to Billy's house. It was also dusk and all around us was the thick, tall grass from which tigers pounce on their prey. . . at dusk.

I tried to convince the driver that his car was up to it. Stumbling blindly around somewhere called Tiger Haven at feeding time seemed as sensible as swimming around somewhere called Shark Haven with a nosebleed. Caroline was made of sterner stuff and said that the walk would do us good. Off we set with our luggage, flinching at every rustle in the under- growth. Caroline developed a bizarre theo- ry that clapping would frighten off any predators. Funny all those munched-up Indians never thought of that.

The farmhouse lights were a godsend and Billy welcomed us in to a huge dinner and a mild reprimand for having walked. A decade earlier, tigers would regularly pick off his workers along that very path. In the last few years, he added wistfully, no one had been attacked. Sadly, Tiger Haven was not the haven it once was. But, even so, one should not take silly risks.

Although, at 78, Billy was no longer the energetic action man from the documen- tary we had seen, he had lost none of his passion for the creature which Mrs Gand- hi adopted as India's national animal at Billy's behest. But his huge files of corre- spondence with a woefully sluggish Indian officialdom showed that he was fighting a losing battle.

For the next few days, we toured Dudhwa looking for tigers. It was a joke. On our first excursion by elephant we went for a mile without seeing any wildlife at all until the elephant driver suddenly stopped. 'Jungle fowl!' he said proudly, pointing at a chicken. There was the odd pug mark (or paw- print) and dropping but nothing more. Billy had explained that vote-hungry politicians were allowing the locals to chop down more and more of the park, driving out the deer which are the tigers' diet. No deer means no tigers.

Eventually, we travelled hundreds of miles south to Ranthambore in Rajasthan, formerly a hunting estate of the maharajas of Jaipur, where the old lodge is now a very smart hotel. We found the widow of the old maharaja and plenty of people in designer safari suits but, again, no tigers. At dawn and dusk, we would set off through the park by jeep, pausing at every bloodied leaf and pug mark our guide could spot. We saw deer and the remnants of the odd ex-deer. We saw suns rise and set over Ranthambore's mesmeric lakeside ruins. But we never saw that glorious flash of orange fur.

Others managed it, and ecstatically broadcast their luck around the hotel din- ing-room. One German woman with a klax- on of a voice which should have scared away all wildlife within miles had even seen a leopard, too. My mood did not improve when I received a message from London that my entire flat had gone up in smoke. The tiger chase would have to wait.

Two years later, covering a royal tour of Asia, I found myself stuck in Nepal for a few days and decided to give the tigers another go. The Royal Chitwan National Park is famous for rhino and also boasts a respectable tiger population, although the poachers continue to lower the numbers.

At dawn and dusk, from the top of an elephant, I scoured the swampy grasslands around the Tiger Tops hotel. By day there were elephant polo lessons. By night there were huge curries and wildlife films in the bar. One night they showed How The Leop- ard Changed Its Spots, reducing a few guests to tears in the process. My thoughts flashed back to Tiger Haven and to Billy's noble, lonely struggle at Dudhwa. Surely there must be some tigers left?

The next morning the elephant was plodding through the mud when a cry went up through the mist. There was a trail. A quartet of elephants and their camera-toting cargoes went careering off. The hunt was .on. Half an hour later it was our elephant which was the first to know. As we approached a dense thicket of 15-foot grass, she stopped in her tracks. The driver whacked her on the head with his stick but she was not budg- ing. Somewhere in that thicket was some- thing nasty.

Other elephants approached from the other side. Suddenly, they were all trum- peting. And then a thunderous roar had us all jumping out of our skins. The grass went bonkers, the elephants went into reverse and I thought I saw a flash of something orange in the chaos. Or did I?

Misty calm soon settled once more but the thrill kept me glowing for days. I had found a tiger. I hadn't actually seen it, of course, but it was definitely there and it sounded like nothing I had ever heard before.

Now all I have to do is see one, and so the wild-goose chase must continue. After all, it is one hell of a wild goose.

Robert Hardman is a columnist and corre- spondent for the Daily Telegraph.

Previous page

Previous page