The turf

Royal rides

Robin Oakley

In Britain racing genuinely has been the sport of kings. Queens, too, have been pretty keen. Nanny Marion Crawford's first encounter with the present monarch was to find her in the bedroom with her dressing- gown cord tied to the bedposts as she urged on an imaginary mount, and the Queen told an early riding instructor that if she were not heir to the throne she would like to have been a lady living in the coun- try with lots of dogs and horses. (She seems to have managed it, some of the time. . . ) Queen Anne, who founded Ascot Race- course, was a passionate follower of hounds and when she became so fat that no horse could carry her she had a two- wheeled chaise specially built in which she drove, at terrifying pace after her buck- hounds.

Perhaps more surprisingly, racing folk owe a considerable debt to Queen Victoria. Her revival of the royal stud at Hampton Court, it seems, had a key influence on the development of the thoroughbred and she remains the only person to have bred the winners of the Derby and the Oaks in the same year.

It hardly accords with the common image of the stout little Queen, normally present- ed as one of those pursed-lips types forever greeting sounds of merriment with an order to someone to 'find out what those people are doing and tell them to stop it'. In fact, she recorded in her diary of her first visit to Ascot: `I was much amused.' On another occasion she told Lord Mel- bourne that she 'had not betted this day, as it bored me', a clear indication that on other occasions she was not averse to plac- ing a small wager with the Ladbroke's of her era. And one day at Ascot she was so excited that she hit her head against a win- dow and broke the glass.

When the young apprentice Macdonald won the Derby of 1940, the year of her marriage to Prince Albert, she invited him up to the Royal Box and asked him what his weight was, she and her Consort both approving when the little lad replied: 'If you please, Your Majesty, my master says I must not tell anyone my weight.'

Other royal involvements with racing are better known. King James I spent so much time at Newmarket that a deputation of 12 was sent from Parliament to complain that he spent too much time on his sport and not enough on affairs of state. They were Promptly warned off the Heath for their pains. Under Charles I, Newmarket became the second capital of the kingdom and Charles 11 not only established the Newmarket Town Plate but rode the win- ner himself in 1673 and 1674. (When Cromwell banned racing in 1650 and dis- persed the royal studs it was not the act of a killjoy. He imported horses himself. It was merely that he feared race meetings might become cover for Royalist rallies.) William III's horses ran frequently at Newmarket, though I suspect he might nowadays have trouble getting registered the animal with which he beat the suppos- edly invincible Careless. He called it Stiff Dick.

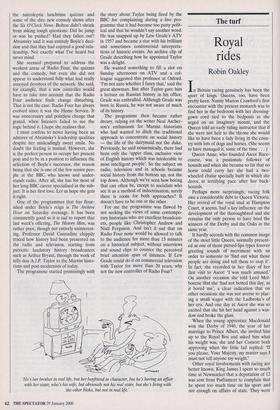

I am indebted for all these details to a sumptuous new book by Arthur Fitzgerald, Thoroughbreds of the Crown: the History and Worldwide Influence of the Royal Studs (limited edition obtainable at pre-publica- tion price of £185 from Genesis Publica- tions, 2 Jenner Road, Guildford GU1 3PL. Tel: 01483 540970). Lavishly produced, it has a wonderful collection of paintings and photographs of royal horses and their descendants. Were I a crazed Californian zillionaire with a vault full of treasures stolen to order, George Stubbs's study of Eclipse and John Frederick Herring Senior's portrait of The Colonel would def- initely be on my shopping-list, although I fear today's stewards would take a dim view of the whip actions revealed in anoth- er favourite, the John N. Sartorius painting of the finish of the Oatlands Stakes in 1791. This is not some glossy coffee-table job but a work of genuine and meticulous scholarship produced over ten years with access to the royal archives. The original documents are intriguing, and the anecdo- tage ensures that this is not a dull com- pendium of couplings.

Although there have been barren periods in the connection between racing and the royals the thread has rarely been entirely broken. George I and George II had no interest but George II's son the Duke of Cumberland, the brutal suppressor of the Jacobite rebellion, was one of the most influential breeders in history. He bred Herod, the champion sire for eight consec- utive years, and also had Spiletta covered by Marske, a great-grandson of the Darley Arabian, to produce the great Eclipse, although he died before the racing days of perhaps the most influential stallion ever. Queen Victoria's contribution was the revival of the royal stud at Hampton Court in 1850 (the sternly moral Prince Albert regarded a royal stud as an appropriate mark of her status) and the sale every sea- son of the yearlings which between them won 1,500 races before her death in 1901.

While on the subject of scholarly and useful works let me recommend also A Century of Champions — Horse-Racing's Millennium Book by the painstaking John Randall and Tony Morris (Portway Press f30). This is a comprehensive account as the title suggests of the careers of the lead- ing horses worldwide over the past 100 years, again beautifully illustrated. There are sections on hurdlers and steeplechasers 'Doesn't look like anyone's going to turn up.' as well as the flat champions, and the authors include a human hall of fame and a crucial tabulation of big-race winners over the century with useful features like largest and smallest winning margins, longest odds, smallest fields etc. Their classifica- tions may start a few arguments but their statistics will settle many more.

Robin Oakley is political editor of the BBC.

Previous page

Previous page