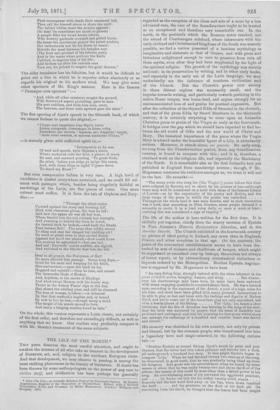

MR. KING'S TRANSLATION OF THE METAMORPHOSES.* ALMOST the only cavil

that a critic is inclined to make while he is. examining Mr. King's volume is whether the work is worth the labour which the writer has spent upon it. For Mr. King, if we The Afelamorphotes of Publius Ovidius Now. Translated into English Blank

Verso. ity Henry Li iug, reLlow of Wadtattn CtiliegO, Oxford. EdLubargh and London: Bleckwood. 1871.

may judge from the effect which he has produced, has not spared labour. We have not found a translator among the many whose work we have examined in these days, when the writers, if not the readers, of translations have so much increased, who has brought to his task a more conscientious and unflagging industry, and who has produced—we have always maintained that industry is at least as much needed as ingenuity—a more satisfactory work of art. But are the Metamorphoses worth it ? They are very far from being Ovid's best work. Though not without fine passages, they are distinctly tedious, and they lack the charm of that exqui- sitely melodious versification which charms us in the elegiac verso of the same author. Nevertheless, they are the work of a great Augustan poet; they offer special advantages for classical teaching, and, as long as our youth learn Latin they will probably continue to be read. All that we need say is, that we have liked them far better in Mr. King's version than we ever liked them—one or two brilliant passages excepted, where Ovid for a brief space reaches Virgilian heights of dignity—in the original.

The translation hitherto best known, though it is not now a volume that is commonly to be met with, is that of "Dr. Garth and others," in which, after the fashion of those days (the early part of the eighteenth century), Ovid is "Englished by various eminent bands." Among these "eminent hands" were both Dryden and Pope, though the latter made but a very small contribution to the volume, and wrote a satirical ballad, entitled "Sandy's Ghost," about it, in which he ridicules the scheme. Dryden, however, wrote a very considerable part of it. We have thus the opportunity of compar- ing Mr. King with the two most famous of English translators, an opportunity the more valuable because, in the instance of Dryden at least, it occurs in the passages where the original rises to its best, in the thirteenth book, containing the " Contest for the arms of Achilles," and the fifteenth, with its fine exposition of the Pythagorean philosophy.

Mr. King shall first enter the lists with Pope in rendering the first part of the story of Dryope (ix. 334-348) :—

Pore. .

"A lake there was with shelving banks around Whose verdant summit fragrant myrtles crowned.

These shades, unknowing of the fates, she sought, And to the naiads flowing garlands brought ;

Her smiling babe (a pleasing charge) she prest

Within her arms, and nourished at her breast.

Not distant far a watery lotos grows; The spring was new, and all the verdant boughs Adorned with blossoms, promised fruits that vie In glowing colours with the Tyriau dye ; Of these she cropped, to please her infant son, And I myself the same rash act had done!

But lo! I saw as by her side I stood The violated blossoms drip with blood ; Upon the tree I cast a frightful look ; The trembling tree with sudden horror shook.

Lotis the nymph (if rural tales be true) As from Priapus' lawless lust she flew, Forsook bar form, and fixing here became A flowery plant which stilt preserves hor name.

This change unknown, astonished at the sight, My trembling sister strove to urge her flight, And first the pardon of the Nymphs implored, And those offended sylvan powers adored.

But when she backward would have fled, she found Her stiffening feet were rooted in the ground.

In vain to free her fastened feet she strove, And as sho struggles only moves above; She feels th' encroaching bark around her grow By quick degrees and oven all below. Surprised at this, her trembling hand F he heaves To rend her hair ; her hand is filled with leaves; Where late was hair the shooting leaves are aeon To rise, and shade her with a sudden green !"

KING.

" A lake there is, from whose low merge the banks Slope upward to a ridge with myrtles crowned. There, ignorant of the Fates, came Dryope

With gift—whose guerdon shame it is to tell—

Of garlands for the Nymphs; and at her breast

Her babe, scarce yet a twelvemonth old, Bile bore,

The pleasing burden suckling as eho wont.

Just ere the lake a purple lotos-bed With plenteous promise blcomed of berried fruit :— And Dryope, to please her infant, culled A flower, and I, who hold her company, The like had done,—but from the severed stalk Oozed crimson drops of blood, and all the loaves With tremulous horror rustled. And, too late, The rueties told how Naiad Lotis, erst From lewd Priapus flying, to that flower Transformed her nature changed, but kept her name. "Could Dryope have known It? Terrified, With hasty homage to the Nymphs, she turned To fly :—her feet clung rooted to the ground And, struggle as she might, her upper part Was all she moved. The hardening bark below Closed round her, spreading, growing, till her form To half its height was veiled. And as she felt Her fate, and strove to rend her hair, her hands With leaves were filled—her locks were only leaves !"

Pope's is a pleasing poem, but it will not stand—we think our readers will agree with us—the comparison. He does not excel, as be commonly does when pitted against moat translators—with Lord Derby, for instance, in the Iliad—in versification. His heroics, which he could not help, so to speak, making good, are certainly not better than the blank verse of Mr. King, with its carefully. modulated rhythm. As versions, there is, of course, no question between them. In the opening lines, where the original runs thus :

"Est lama, aeclivis devexo margin° formatn Litoris efficiene. Summum myrteta aeronaut,"

the modern, as might be expected, is precise, the older poet vague ; " quoque Indignere magis," though not very happily given by " whose guerdon shame it is to tell," is entirely omitted by Pope ; so is " qui nondurn irnpleverat annum," unless we have it in "smiling ;" the colour is attributed to the fruits instead of the flowers, though Mr. King's " purple" is not picturesque enough for 4"I'yrios imitate colores." "If rural tales be true" looks like a mistranslation of " referunt tardi nuno denique agrestes." The last line represents nothing in the original. How closely and ingeniously Mr. King translates may be seen by comparing the last few lines of the original, which we subjoin :— " Haeserunt ratlice pedse. Convellore pugnat

Noe quicquem nisi aumme. moret. Suberoseit ab imo Totaque paulatirn lontus premit inguina cortex.

Ut vidit, conata menu laniare capillos, Fronde manum liuplevit. Frondes caput emu° tenebant."

We will now see how Mr. King gives us Pythagoras' vegetarian- ism (xv. 116-137) :—

"Bat ye—

What had ye done, yo flocks, yo peaceful race Created for Man a blessing, that provide To slake his thirst your udder's nectarous draught, That with your fleece wrap warm his shivering limbs, And serve him hotter with your life than death ?— What fault was in the Ox, a creature mild And harmless, docile, born with patient toil

To lighten half the labour of the fields ?—

Ungrateful ho, and little worth to reap The crop he sowed, that, from the crooknd share Untraeed, his ploughman slew, and to the axe Condemned the nook that, worn beneath his yoke, For many a Spring his furrows traced, and home With many a harvest dragged his Autumn-wain!

Nor this is all :—but Man must of his guilt Make Heaven itself accomplice, and believe The Gods with slaughter of their creatures pleased !

Lo! at the altar—fairest of his kind,—

And by that very fairness marked for doom,— The guiltless victim stands,—bedecked for death With wreath and garland 1—Ignorant he hears The muttering Pliest,—feels ignorant his brows White with the sprinkling of the salted meal To his own labour owed,—and ignorant Wonders, perchance, to see the lustral urn Flash back the glimmer of the lifted knife Too soon to dim its brightness with his blood And Priests are found to teach, and men to deem That in the entrails, from the tortured frame Yet reeking torn, they read the hest of Heaven

This is a very fine passage, and will bear, and more than bear, comparison with the

'We will now give Drydeu's version, first, however, letting our

readers see a sample of the way in which translators then dealt with their originals,—the characteristic couplet which he foists into Ovid's description of the sacrifice of the boar to Ceres, the goat to Bacchus :— "In vengeance laity and clergy join,

Whore one has lost his profit, one his wine.

"Hero was at least some shadow of offence, The sheep was sacrificed on no pretence, But meek and unresisting innocence.

A patient, useful creature, born to bear

The warm and woolly fleece, that clothed her murderer,

And daily to give down the milk she bred, A tribute for the grass on which she fed.

Living both food and raiment she supplies, And is of least advantage when she dies.

"How did the toiling ox his death deserve, A downright, simple drudge, and born to servo ? 0 tyrant! with what justice canst those hope The promise of the year, a plenteous crop ; When thou destroyost thy lab'ring steer, who till'd, And ploughed, with pain, thy also ungrateful field? From his yet reeking neck to draw the yoke (That neck with which the surly clods ho broke), And to the hatchet yield thy husbandman Who finished autumn and the spring began ? Nor this alone, but, Heaven itself to bribe, 'We to the gods our impious acts ascribe ; First recompense with death their creatures' toil, Then call tho blessed above to share the spoil: Tho fairest victim must the powers appease: (So fatal 'tie sometimea too much to please) A purple fillet his broad brows adorns With flowery garlands crowned and gilded horns. He hears the murderous prayer the priest prefers, But understands not 'tis his doom he hears: Beholds the meal between his temples cast (The fruit and product of his labours past), And in the water views perhaps the knife Uplifted, to deprive him of his life ; And broken up alive his entrails sees

Torn out, for priests to inspect the gods' decrees."

The older translator has his felicities, but it would be difficult to point out a line in which he is superior either absolutely or as regards his original to his modern rival. We may give some other specimen of Mr. King's manner. Here is the famous " Pronaque cum spectent " :—

" And, while all other creatures sought the ground, With downward aspect grovelling, gave to man His port sublime, and bade him scan, erect, The heavens, and front with upward gaze the stars."

The fine opening of Ajax's speech in the fifteenth book, of which we cannot forbear to quote the original,—

"Utquo orat impatiens irae Sigiiia torvo Liters oonspoxit, classetnque in litoro voltu,

Intondons quo menus, Agimus, pro Juppiter,' Ante rates causain, et mecum oonfortur "

—is scarcely given with sufficient spirit in,— " Intemperate as he was Of soul and speoub, upon Sigamtn's shore, Where anchored rode the fleet, a glance of scorn He oast, and seaward pointing, Ye great Gods,' He cried, 'before you ships yo judge this cause, And, with those ships in sight; Ulysses dares To stand my Rival "

But even comparative failure is very rare. A high level of excellence is alinest everywhere sustained, and we could fill col- amne with passages which, besides being singularly faithful as renderings of the Latin, are fine pieces of verse. One more extract must suffice. It is from the tale of Orpheus and Eury- dice :—

" Through the silent realm Upward against the stoop and fronting hill, Dark with obscurest gloom, the way he led : And now the upper air was all but won, When, fearful lost the toil o'ortask her strength, And yearning to behold the form he loved, An instant hack ho looked,—and back the Shads That instant fled! The arms that wildly strove To clasp and stay her clasped but yielding air! No word of plaint even in that second Death Against her Lord she uttered,--bow could Love Too anxious be upbraided ?—but one last And sad 'Farewell,' scarce audible, she sighed, And vanished to the Ghosts that late she left.

. . ..... . . .

IDeaf to all prayer, the Ferryman of Holt

No more allowed him passage. Seven long days,—

Grief for his meat and weeping for his drink, Else nurtureless,—upon the bank he lay, Haggard and squalid :—then he rose, and cursed

The inexorable Gods of Erebus'

And, hopeless, to the snows of Rhodope And wind-swept Hannus took his lonely way, Thrice in the watery Pisces' sign to the Sun

Had closed the circling year, and still he shunned

The face of woman, loveless ;—or deterred By that first wedlock's hapless end, or bound By vow to her lie lost ;—though many a maid The magic of his mush, moved to love, And many a longing maiden loved in vain."

On the whole, this version represents a Latin classic, not certainly of the first order, and therefore not exceedingly difficult, as well as anything that we know. Our readers may profitably compare it with Mr. Morris's treatment of the same subjects.

Previous page

Previous page