WHAT ABOUT THE WORKERS?

When the vanguard of the workers downs tools in the

r

workers' state', it is time for the rulers to panic. Stephen Handelman

reports on the Soviet miners' strike

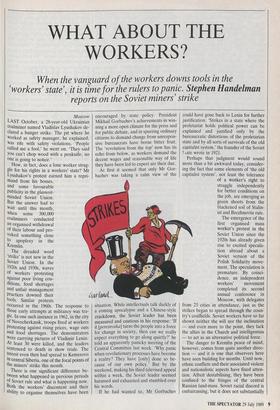

Moscow LAST October, a 28-year-old Ukrainian coalminer named Vladislav Lyushakov de- clared a hunger strike. The pit where he worked as safety manager, he explained, was rife with safety violations. 'People called me a fool,' he went on. 'They said You can't chop wood with a penknife, no one is going to notice.'

The dreaded word 'strike' is not new in the Soviet Union. In the 1920s and 1930s, waves of workers protesting against poor living con- ditions, food shortages and unfair management Practices downed their tools, Similar protests occurred in the 1960s. The response to those early attempts at militancy was tra- gic. In one such instance in 1962, in the city Of Novocherkassk, troops fired at workers Protesting against rising prices, wage cuts and food shortages. The demonstrators were carrying pictures of Vladimir Lenin. At least 30 were killed, and the leaders sentenced to death in show trials. The unrest even then had spread to Kemerovo in central Siberia, one of the focal points of the miners' strike this month.

There is one significant difference be- tween what happened in previous periods of Soviet rule and what is happening now. Both the workers' discontent and their ability to organise themselves have been encouraged by state policy. President Mikhail Gorbachev's achievements in win- ning a more open climate for the press and for public debate, and in spurring ordinary citizens to demand change from unrespon- sive bureaucrats have borne bitter fruit. The 'revolution from the top' now has its echo from below, as workers demand the decent wages and reasonable way of life they have been led to expect are their due. At first it seemed that only Mr Gor- bachev was taking a calm view of the

situation. While intellectuals talk darkly of a coming apocalypse and a Chinese-style crackdown, the Soviet leader has been measured and cautious in his response: 'If it [perestroika] turns the people into a force for change in society, then can we really expect everything to go along quietly?' he told an apparently panicky meeting of the Central Committee last week. 'Why panic when revolutionary processes have become a reality? They have [only] done so be- cause of our own policy.' But by the weekend, making his third televised appeal within a week, the Soviet leader seemed harassed and exhausted and stumbled over his words.

If he had wanted to, Mr Gorbachev could have gone back to Lenin for further justification: 'Strikes in a state where the proletariat holds political power can be explained and justified only by the bureaucratic distortions of the proletarian state and by all sorts of survivals of the old capitalist system,' the founder of the Soviet Late wrote in 1921.

The emergence of the first organised mass worker's protest in the Soviet Union since the 1920s has already given rise to excited specula- tion abroad about a Soviet version of the Polish Solidarity move- ment. The speculation is premature. By coinci- dence, an independent — and even more to the point, they lack the allies in the Church and intelligentsia — to act as an alternative political force.

The danger to Kremlin peace of mind, however, comes from quite another direc- tion — and it is one that observers here have seen building for months. Until now, ethnic conflicts and their associated violent and nationalistic aspects have fixed atten- tion. Albeit destabilising, they have been confined to the fringes of the central Russian land-mass. Soviet racial discord is embarrassing, but it does not substantially threaten the country's power balance.

Unrest in the Russian heartland is some- thing else. 'I've got the same problems as they have,' grumbled one office worker in Moscow last week, when she read about the concessions already offered to the miners. `Should I go on strike too to get what I want?' Ever since the election campaign to the Supreme Soviet this spring, the discontent of ordinary people with their economic lot has been vividly apparent. Mass demonstrations in Moscow and other large Russian cities boiled with rhetoric about empty food shops and the privileges enjoyed by a remote, unrespon- sive Party apparatus. Party secretaries in many cities went down to stunning defeat in places where they were challenged by populist candidates and even where they ran unopposed, as people simply crossed their names off the ballot.

Since the beginning of this year, there have been strikes throughout the Russian heartland. Miners in Norilsk went on strike for five days in April, refusing to come above ground in a protest against 'despotic bosses'. In February, miners in the Donbass region of the Ukraine refused to sign a new labour contract until they were guaranteed better municipal services and higher pay. And it has not only been miners. Quarry workers, air traffic controllers, shop assis- tants and even, in a short-lived protest, a group of policemen in Leningrad have walked out in a painful demonstration of Lenin's warning about 'bureaucratic distor- tions'.

The variety of occupations and profes- sions affected by labour militancy signals a universal dismay which, unlike the West- ern variety of industrial dispute, has less to do with specific industry-related issues than with the general state of the nation. The appalling conditions in which many workers find themselves are a common factor behind the present unrest. Listen, again to Mikhail Gorbachev, about a visit he paid earlier this month to a Leningrad factory preparing materials for construc- tion: 'Conditions are at the early 18th- century technological level. You wouldn't believe your eyes . . . even a simple thing like installing ventilation has been discus- sed for two years, while the staff, mostly women, work in clouds of dust. We ought to be ashamed, all of us.'

Soviet figures suggest that this country has one of the worst safety and occupation- al health records in the industrialised world. Last year, more than 14,000 people were killed in on-the-job accidents in the Soviet Union. 'In 1988, we suspended the work of 235,000 machine tools and closed down 4,200 shops because their further operations threatened the health and even the lives of workers,' reported V. Sorokin, chief technical inspector of the national council of trade unions. Every year, he claimed, his technical inspection teams uncover three million violations of safety rules. Present conditions in Soviet mining and resource industries underline the dilemma of an economy fighting to survive on the worn backs of its participants. In the Donbass region of the Ukraine, where Mr Lyushakov staged his hunger strike, figures showed between two and three deaths for every ton of coal extracted. 'Under the guise of perestroika', a recent booklet produced at the Soviet Union's first-ever conference on occupational health last autumn claimed, `safety allocations are being slashed. . . . The new economic mechanism may start operating at the expense of people's safety unless urgent measures are taken.'

What measures? Soviet miners, like their Western cousins, have been the van- guard of the working class. Appropriately, the 35-point package of demands they presented to the government is a distilla- tion of the nationwide frustration: better housing and working conditions, better pensions, secure food supplies and, with a nod towards democracy, a greater say in the operations of the workplace.

It is no coincidence that one of the concrete responses envisioned by the au- thorities is the preparation of long overdue strike legislation. The recognition that conflicts are inevitable in a period of fundamental change, whether the system is called socialist or capitalist, is a significant step. Only last autumn Stepan Shalayev, chairman of the all-union central council of

trade unions, the now universally despised state bargaining body for workers, warned that strikes in a socialist system were self-defeating. Now, even regional party secretaries are jumping on the bandwagon. 'We have been too slow to settle the burning issue [of strikes],' commented Oleg Shenin, the Communist Party boss of the Krasnoyarsk region. 'We need legisla- tion [providing for] the right to strike.' He added, almost as an afterthought, 'What we need even more is efficient economic management.'

Economic unrest is not likely to end with the settlement of the miners' dispute which, in the Ukraine at least, appears to have been resolved. The threat of a nation- wide rail strike on 1 August, which pro- voked an unscheduled address by Mr Gorbachev to the nation's parliament warning that the government might be forced to take harsher measures, is just one of the symptoms of the mounting impati- ence with the pace of reforms.

Anyone who travels in this country outside Moscow cannot help being aware of the anger. Earlier this year, officials disclosed that some 40 million Soviet peo- ple live on or below what the state regards as the minimum standard of living— that is to say less than 75 roubles a month. Two thirds of those who answered an opinion survey taken by a central committee think- tank recently said they had not seen any improvement in their material conditions in the last five years. `For 15 per cent, things have got worse,' the report said.

The sympathetic treatment of the strikes by the national press is another indication that the contradictions of perestroika are sharpening debate and raising political consciousness in the Soviet heartland. `Who can blame the workers?' asked the Sovietskaya Rossiya newspaper. 'Haven't they tried for many years to get their problems heard? The ones who are to blame for what is happening are those who don't listen, who were afraid.'

Fear is rising indeed among the appar- atchiki. In his various meetings with the Party elite during the crisis, Mr Gorbachev has been deluged with demands that he wield a 'strong stick' before things get worse. In response, he has signalled a purge of conservative elements in the nationwide Party apparatus. 'The so-called good old days will never be back,' he warned, 'though some are still looking forward to their return.' Aligning himself more and more openly with the popular mood, Mr Gorbachev is showing his un- erring political instinct for survival. It is the only hope he has of strengthening his own increasingly ambiguous position with the new Soviet 'electorate'. Cannily, even Boris Yeltsin was brought back in from the cold to add his voice to appeals to the miners for reason by leading government figures.

Soviet officials have been as stunned as Western observers by the organisational abilities of the miners. Strike committees patrolled the streets of Kemerovo and Mejhduruchensk, local liquor stores were Closed, militia and strikers shared the task of keeping order at rallies. In a country Where strikes were regarded as counter- revolutionary, 'wrecking' and a betrayal of the working class, it was long assumed that such abilities, the collective gene for labour militance, if you will, had been destroyed long ago in the frozen prisons of Siberia. But we were similarly astonished when the Soviet electorate rose up in the spring to demonstrate its sophistication.

Previous page

Previous page