Her heart belonged to Daddy

Frances Partridge

ANNA FREUD: A BIOGRAPHY by Elisabeth Young-Bruehl

Macmillan, £18.95, pp.527

FREUD by Anthony Storr

OUP, £3.95, pp.135

......„

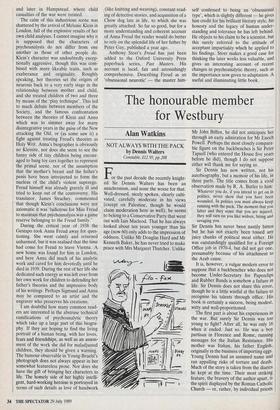

he two female photographs on the dust-cover of Professor Young-Bruehl's book give us a preview of what is in store: on the front is Anna Freud herself — Jewish, intelligent, sympathetic and sensi- tive to the point of painful vulnerability, and at the back her biographer Elisabeth — American, confident, direct, with a humorous, tomboy expression.

When Anna died, less than a year after a serious stroke but perfectly clear in the head, she seems to have had little desire for any biography of herself to be written. Her last months had held few gleams of happiness; several of her dearest friends had died, and she left the British Psychoanalytical Society in some disarray. 'I never knew one could be so miserable,' was her comment on her state, and when asked by a pretty young nurse to watch herself in a mirror trying to walk, she said with a touch of the humour which was not unlike her father's, 'I'd rather look at you.'

Her literary executor invited Elisabeth Young-Bruehl to write a biography and gave her full access to Anna's papers. She has also drawn from the Freud museums in Vienna and London, as well as from the annals of the Hampstead children's clinic — the most practical result of Anna's life work. But however influential this work has been, she will chiefly be remembered as Sigmund Freud's favourite daughter, and what will most interest the common reader is the light this book throws on his work and their relationship. That it was veneration on her side and protective love on his is generally known. She was his constant companion with whom he could discuss his ideas as he could not with her mother; his most gifted child, his 'Anti- gone', his 'great mainstay in all things' and 'a particularly dear and interesting crea- ture'. He took holidays abroad with her, and when cancer struck him she became his devoted nurse. Although he more than once declared that he was worried by the unnaturally chaste and childless life she was leading, he never seems to have encouraged any of her suitors, who in- cluded Ernest Jones.

Anna was born in the same year that the Interpretation of Dreams saw the light. As a child she was a day-dreamer, wrote poetry, and was jealous of her mother and her nearest sister Sophie, who was thought prettier than her. As a young girl she attended her father's lectures and decided that she wanted to be an analyst. Some criticism has been levelled at Freud for undertaking her analysis himself, but this was not unusual — Jung, Abraham and Melanie Klein all analysed their own child- ren. By the age of 30 Anna had had four years of analysis, was a certified teacher, had embarked on child analysis and joined the executive board of the Vienna Associa- tion. For the rest of her life her interest in child psychology inspired the love and energy she put into her work. She made many friends among other psychoanalysts: one with Lou Andreas-Salome (a figure who glides through the literature of the movement like a waft of sophisticated scent in a corridor) and another with Dorothy Burlingham, an American who had left her psycho-neurotic husband and come to England with her four children for I them all to be analysed. Young-Bruehel rightly gives her a prominent role in I Anna's life. They were close friends who I took relaxed holidays together and shared the work of Anna's clinics, first in Vienna and later in Hampstead, where child casualties of the war were treated.

The calm of this industrious scene was shattered by the arrival of Melanie Klein in London, full of the explosive results of her own child analyses. I cannot imagine why it is supposed that the characters of psychoanalysts do not differ from one another as those of other people do. Klein's character was undoubtedly excep- tionally aggressive, though this was com- bined with more likeable traits, such as exuberance and originality. Roughly speaking, her theories set the origins of neurosis back to a very early stage in the relationship between mother and child, and she treated children of two and three by means of the 'play technique'. This led to much debate between members of the Society, and the famous confrontation between the theories of Klein and Anna which was to simmer away for many disintegrative years in the guise of the New attacking the Old, or (as some saw it) a fight against treating Freud's theories as Holy Writ. Anna's biographer is obviously no Kleinite, nor does she seem to see the funny side of tiny children being encour- aged to bang toy cars together to represent the primal scene, nor of the assumption that the mother's breast and the father's penis have been introjected to form the nucleus of the child's violent superego. Freud himself was already gravely ill and tried to keep out of the controversy. His translator, James Strachey, commented that though Klein's conclusions were not axiomatic it was 'ludicrous for Miss Freud to maintain that psychoanalysis was a game reserve belonging to the Freud family.'

During the critical year of 1938 the Gestapo took Anna Freud away for ques- tioning. She went calmly and returned unharmed, but it was realised that the time had come for Freud to leave Vienna. A new home was found for him in London, and here Anna did much of his analytic work and cared for him devotedly until he died in 1939. During the rest of her life she dedicated such energy as was left over from her own work for children to defending her father's theories and the impressive body of his writings. Perhaps Sigmund and Anna may be compared to an artist and the engraver who preserves his creations.

I am doubtful how many common read- ers are interested in the abstruse technical ramifications of psychoanalytic theory which take up a large part of this biogra- phy. If they are hoping to find the living portrait of a human being, with her loves, fears and friendships, as well as an assess- ment of the work she did for maladjusted children, they should be given a warning. The humour observable in Young-Bruehl's photograph does not always appear in her somewhat featureless prose. Nor does she have the gift of bringing her characters to life. The homely side of her highly intelli- gent, hard-working heroine is portrayed in terms of such details as love of handwork (like knitting and weaving), constant read- ing of detective stories, and acquisition of a Chow dog late in life, to which she was greatly attached. So far so good, but for a more understanding and coherent account of Anna Freud the reader would do better to rely on the splendid life of her father by Peter Gay, published a year ago.

Anthony Storr's Freud has just been added to the Oxford University Press paperback series, Past Masters. His account is lucid, fair and astonishingly comprehensive. Describing Freud as an 'obsessional neurotic' — the master him- self confessed to being an 'obsessional type', which is slightly different — he gives him credit for his brilliant literary style, his honesty and the legacy of human under- standing and tolerance he has left behind. He objects to his claim to be a scientist, but this surely referred to the attitude of acceptant impartiality which he applied to his findings. Storr makes a good case for thinking the later works less valuable, and gives an interesting account of recent changes in psychoanalytic theory, such as the importance now given to adaptation. A useful and illuminating little book.

Previous page

Previous page