Exhibitions

Constable (Tate Gallery, till 15 September) Kaff Gerrard: the Ripening Seed (Royal Museum and Art Gallery, Canterbury, till 6 July)

Visions of England

Giles Auty

This week presents me with the chance to write about Britain's best-known land- scape painter together with one of the least known. Kaff Gerrard (1894-1970) may well be that rarest of commodities: an unknown or undiscovered artist whose work was brushed, at least, with a touch of genius. Katherine Gerrard, née Leigh-Pemberton, was married to A.H. Gerrard who is a for- mer professor of sculpture at the Slade and still alive. Her paintings were never exhibit- ed during her lifetime. The fact that they are so now is a tribute to the sculptor David Thompson, who knew her, and to a band of loyal helpers who have managed to put on the present exhibition of 74 oil paintings at Canterbury. Many more works exist which have not been exhibited. A still more ambitious exhibition should be arranged forthwith at a more central venue; a gallery such as the Serpentine would be ideal. Not to do so would deprive art lovers of an experience offering rich and surprising rewards.

By contrast, John Constable (1776-1837) certainly did not hide his light under a bushel as an artist but strove constantly, with varying degrees of success, for profes- sional recognition. However, he was not made a Royal Academician until in his 53rd year and was elected then by a single vote only, over Francis Danby. When one looks at the state of the Royal Academy today and at much of the work offered annually by members as well as non-mem- bers, it is hard not to reflect a little on the nature of supposed progress.

Constable was not helped in his career by a predilection for landscape, which was looked down on as an art form in his day and has remained so largely since, if for somewhat different reasons. Nevertheless, landscape painting and pastoral romanti- cism remain central to English sensibility. Far from being ashamed of this natural leaning, I believe we should revel in it and enjoy the life-enhancing nature of bucolic experiences to the full. Constable sets us all an example here, for his mature work dis- plays not only great skill but a range of potent emotions engendered in him by the landscape.

The current Tate Gallery show features over 340 works. It thus helps underline again Constable's deserved status as a major figure of 19th-century art. I believe unusual talent was noticeable even in some of the less regarded works of his youth, when beautiful tone and clarity were appar- ent already. The two paintings the artist made in 1815 of the gardens at the back of East Bergholt House seem to me to be charged with personal feeling of extraordi- nary poignancy. It is significant the artist never exhibited or sold them. His painting Vivenhoe Park, Essex' of a year later is likewise the most intense evocation I can recall of an English summer morning.

The more sultry and overcast paintings of later years mirror the build-up of clouds in the artist's own life, notably the failure of his wife's health. Landscape painting is often a metaphor for vanished innocence and for childhood days when the country- side can appear heartrending in its beauty. Constable reminds us of experiences which are available to almost all of us, although I think these days that fewer and fewer peo- ple are habitual wanderers through our landscape. Of course, the artist's paintings are records also of his inner and spiritual life. Thus 'Salisbury Cathedral from the Mead- ows' is a painting of exceptional richness and depth both in imagery and sentiment. Like the landscape and building which inspired the painting in the first place, it is a work which rewards long and peaceful contemplation. Unfortunately on my sec- ond visit to the Tate Gallery show I was surrounded by small boys who moved like clockwork mice but sounded like Daleks. Each, so as to listen to an explanatory cas- sette, was strapped into a headset which was turned up presumably to full volume. I cannot guess whether the tapes in question provide useful education for small children. Most likely they are no duller or more mis- leading than Open University art pro- grammes on television. But surely the main point of the current Constable exhibition is that it is a visual feast of a kind which has become increasingly rare. Today it is in the use of eyes rather than ears that art educa- tion is lacking so woefully.

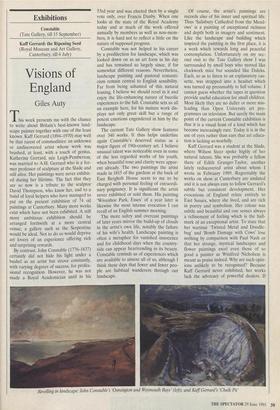

Kaff Gerrard was a student at the Slade, where Wilson Steer spoke highly of her natural talents. She was probably a fellow there of Edith Granger-Taylor, another lately rediscovered artist about whom I wrote in February 1989. Regrettably the works on show at Canterbury are undated and it is not always easy to follow Gerrard's subtle but consistent development. Her evocations of England relate entirely to East Sussex, where she lived, and are rich in poetry and symbolism. Her colour was subtle and beautiful and one senses always a refinement of feeling which is the hall- mark of an exceptional artist. To state that her wartime 'Twisted Metal and Doodle- bug' and 'Bomb Damage with Cows' lose nothing by comparison with Paul Nash or that her strange, mystical landscapes and flower paintings excel even those of so good a painter as Winifred Nicholson is meant as praise indeed. Why are such opin- ions unlikely to be recognised? Because Kaff Gerrard never exhibited, her works lack the advocacy of powerful dealers. If Revelling in landscape: John Constable's Vsmington and Weymouth Bays' (left), and Kaff Gerrard's 'Chalk Pit' our museum curators looked for them- selves more and listened less, our national and regional art collections might be immeasurably richer.

Previous page

Previous page