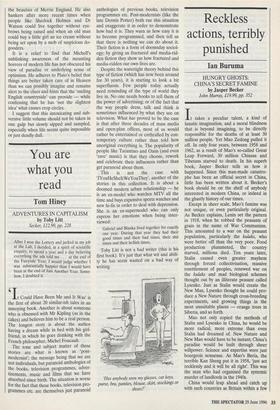

Reckless actions, terribly punished

Ian Buruma

HUNGRY GHOSTS: CHINA'S SECRET FAMINE by Jasper Becker John Murray, £19.99, pp. 352 It takes a peculiar talent, a kind of lunatic imagination, and a moral blindness that is beyond imagining, to be directly responsible for the deaths of at least 30 million people. Yet Mao Zedong pulled it off. In only four years, between 1958 and 1962, as a result of Mao's so-called Great Leap Forward, 30 million Chinese and Tibetans starved to death. In his superb book, Jasper Becker tells us how it happened. Since this man-made catastro- phe has been an official secret in China, little has been written about it. Becker's book should be on the shelf of anybody interested in modern China, or indeed in the ghastly history of our times.

Except in sheer scale, Mao's famine was not unique, or even particularly original. As Becker explains, Lenin set the pattern in 1918, when he robbed the peasants of grain in the name of War Communism. This amounted to a war on the peasant population, particularly the kulaks, who were better off than the very poor. Food production plummeted, the country starved, millions died. Ten years later, Stalin caused even greater mayhem through forced collectivisation, massive resettlement of peoples, renewed war on the kulaks and mad biological schemes thought out by an illiterate peasant called Lysenko. Just as Stalin would create the New Man, Lysenko thought he could pro- duce a New Nature through cross-breeding experiments, and growing things in the most unsuitable places — orange trees in Siberia, and so forth.

Mao not only copied the methods of Stalin and Lysenko in China, he would be more radical, more extreme than even Stalin had dreamed of. New Nature and New Man would have to be instant; China's paradise would be built through sheer willpower. Science and expertise were just bourgeois nonsense. As Mao's Beria, the terrible Kan Sheng put it in 1958, 'just act recklessly and it will be all right'. This was the man who had organised the systemic murder of landlords in the 1940s.

China would leap ahead and catch up with such countries as Britain within a few years. To this purpose, people were told to melt down all metal objects, including their pots and pans, and build furnaces in their backyards. Farms were collectivised, and the wrong crops planted, in the wrong way. Dams were constructed by party hacks who had no idea about engineering. Fantastic grain quotas were set. 'Bumper harvests' would astonish the world. Self-sufficiency would not be enough; China would export food in abundance.

Naturally, the bullied, impoverished peasants could not come near to fulfilling the quotas, which were all a fantasy any- way. But to admit this would be 'counter- revolutionary'. So the party cadres would rob all the food and grain they could from the peasants, and make up the statistics to fit the officially propagated fantasies. Soon people began to starve in large numbers. Those who tried to escape from famine areas were shot. Like Lenin and Stalin had done before him, Mao went to war against his own people.

The official lying about production fig- ures could never really hide the disastrous effect all this was having on agriculture. There were no bumper harvests. There was often no food at all. But the fantasy had to be sustained. So the peasants were accused of hoarding grain. People, half-crazed with hunger, were punished with torture or death if they were caught eating grass while working in the fields. People were so des- perate, they would prise apart manure under horses hooves in search of undigest- ed grain. The last resort was cannibalism. In some cases, parents ate their own children, the daughters first, then the sons.

Mao himself ate well, and never saw any- thing that would have disturbed his sleep. Wherever he turned up, local cadres would organise an elaborate stage-set of abundant crops and smiling people. Many leading officials around Mao knew perfectly well what was happening, but apart from one or two brave exceptions (who were later purged and killed), no one dared to tell the Great Helmsman that his fantasy was not only mad but murderous. The charming Zhou Enlai, the most popular man on the diplomatic circuit, never said a word. Deng Ziaoping, the great reformer, defended the Great Leap Forward, and Zhao Zeyang, the other great reformer, did his best to persecute starving people for 'hoarding'.

Becker's book is a horrifying read. He describes what happened in more detail than I have seen before. His account is based on documentary evidence, travel to the actual places where the worst atrocities took place, and on conversations with sur- vivors. But his book is not just descriptive. He offers conclusive evidence that the next cataclysmic event in Chinese history, the Cultural Revolution, was a result of the Great Leap Forward. By 1961, even Mao realised something had gone badly wrong, but he blamed the famine on sabotage by counter-revolutionaries and reactionary elements. His failure was so monumental, however, and the danger of a total collapse in China so great, that such leading figures as Liu Shaoqi, began to take over and did what they could to undo the damage. Mao withdrew, and sulked in his palaces, often in the company of young girls. His supremacy had been challenged, and he brooded on ways to reassert his absolute power.

The time came, a few years later, when Mao and his supporters unleashed the younger generation on the 'capitalist road- ers' who had dared to challenge him. Everyone who had tried to stop the famine, and thus implicitly challenged Mao's divine wisdom, was now fair game. Again, as in earlier purges, countless people died. Liu Shaoqi was arrested, tortured and left to die horribly in jail.

While all this went on, there was always a stream of Western China-experts, Sinophiles and useful idiots who visited China and came back with glowing reports. Becker mentions most of them. Han Suyin, for example, could always be counted on to promote every twist and turn of Mao's pro- paganda. Francois Mitterrand, after tour- ing China in 1961, called Mao a 'humanist', and denied there was any famine in China. Joseph Needham, Felix Greene (brother of Graham), Wilfred Burchett . . The list goes on. All saw nothing untoward; all were witness to a grand future. Some were misguided idealists. Others were hardened propagandists.

Reading what the likes of Han Suyin have written about China over the years, it is hard to contain one's rage. One wishes they could be punished somehow, just as Nazi propagandists have often been pun- ished. It will not happen. The legacy of anti-fascism has made the Left immune. But I could think of no more fitting punish- ment than to force-feed some of them, page by page, Jasper Becker's book.

Previous page

Previous page