ARTS

Looking through the glass

Simon Courtauld talks to the octogenarian glass engraver Laurence Whistler Good Lord, I thought he died years ago,' has been the most common reaction of those to whom I have mentioned my recent meeting with the glass engraver, Laurence Whistler. At 84 he is alive and well and working on a prism. It depicts a leaning tree trunk that doubles as the glass slowly revolves, and becomes two arms holding up a crown concealed in the foliage. The three circles of the Trinity are bathed in light and the words 'Amor Vincit Omnia' come and go.

Whistler's best-known prism is dedicated to his artist brother Rex, who was killed in Normandy in 1944. It is to be found in a side-chapel in Salisbury Cathedral, showing half the building and spire, which turn into the whole and then vanish. In the sky is the house in the Close where they both lived.

I kept watching the revolution of the glass, looking for a double entendre or a hidden meaning in the engraving, which is characteristic of so much of Whistler's work. But there seemed to be nothing recondite about this beautiful tribute to his brother's memory. In his studio at Scriber's Cottage in Watlington, Oxfordshire, Whistler explained the great advantage of working with glass — 'because it has a nat- ural quality of ambiguity and illusion'. He went on to quote from George Herbert's 17th-century hymn:

A man that looks on glass, On it may stay his eye; Or if he pleaseth, through it pass, And then the heaven espy.

Until Whistler started his glass engraving in the mid-1930s, there had been virtually no point engraving in Britain for the past 200 years. By coincidence, two others began engraving at the same time as Whistler, and a Guild of Glass Engravers was established, which today has around 400 members.

`There is much more wheel engraving these days, for instance in the United States,' Whistler told me; tut it does not combine well with the dot and stipple work which I do.' He starts with a wax pencil, then uses a fine tool of hardened steel, and sometimes a small electric drill for softer effects.

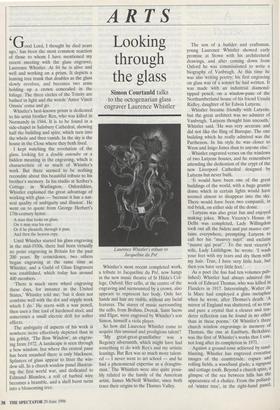

The ambiguity of aspects of his work is nowhere more effectively depicted than in his goblet, 'The Bow Window', an engrav- ing from 1972. A landscape is seen through a bow window, but where the central pane has been smashed there is only blackness. Splinters of glass appear to litter the win- dow sill. In a church window panel illustrat- ing the first world war, and dedicated to Edmund Blunden, a roll of barbed wire becomes a bramble, and a shell burst turns into a blossoming tree. Laurence Whistler's tribute to Jacqueline du Pre Whistler's most recent completed work, a tribute to Jacqueline du Pre, now hangs in the new music theatre of St Hilda's Col- lege, Oxford. Her cello, at the centre of the engraving and surmounted by a crown, also appears to represent her body. Only her hands and hair are visible, without any facial features. The staves of music surrounding the cello, from Brahms, Dvorak, Saint Saens and Elgar, were engraved by Whistler's son Simon, himself a viola player.

So how did Laurence Whistler come to acquire this unusual and prodigious talent?

'My great-great-grandfather was a Regency silversmith, which might have had something to do with Rex's and my artistic leanings. But Rex was so much more talent- ed — I never went to art school — and he had a phenomenal expertise as a draughts- man.' The Whistlers were also quite possi- bly related to the family of the American artist, James McNeill Whistler, since both trace their origins to the Thames Valley. The son of a builder and craftsman, young Laurence Whistler showed early promise at Stowe with his architectural drawings, and after coming down from Oxford he was commissioned to write a biography of Vanbrugh. At this time he was also writing poetry; his first engraving on glass was of a sonnet he had written. It was made with an industrial diamond- tipped pencil, on a window-pane of the Northumberland house of his friend Ursula Ridley, daughter of Sir Edwin Lutyens.

Whistler became friendly with Lutyens, but the great architect was no admirer of Vanbrugh. lutyens thought him uncouth,' Whistler said. 'He was very accurate and did not like the fling of Baroque. The one building which he really admired was the Parthenon. In his style he was closer to Wren and Inigo Jones than to anyone else.'

Whistler engraved verses on the windows of two Lutyens houses, and he remembers attending the dedication of the crypt of the new Liverpool Cathedral designed by Lutyens but never built.

`It would have been one of the great buildings of the world, with a huge granite dome which in certain lights would have seemed almost to disappear into the sky. There would have been two campanili, in red brick, on either side of the dome.

`Lutyens was also great fun and enjoyed making jokes. When Viceroy's House in Delhi was completed, Lady Willingdon took out all the bidets and put mauve cur- tains everywhere, prompting Lutyens to call her his "mauvey sujet" and exclaim "mauve qui peut".' To the next viceroy's wife, Lady Linlithgow, he wrote: 'I wash your feet with my tears and dry them with my hair. True, I have very little hair, but then you have very little feet.'

As a poet (he has had ten volumes pub- lished) Whistler had always admired the work of Edward Thomas, who was killed in Flanders in 1917. Interestingly, Walter de la Mare had employed a glass metaphor when he wrote, after Thomas's death: 'A mirror of England was shattered, of so true and pure a crystal that a clearer and ten- derer reflection can be found in no other than in these poems.' Of Whistler's three church window engravings in memory of Thomas, the one at Eastbury, Berkshire, was the first of Whistler's works that I saw, not long after its completion in 1971. Against a ground-tone achieved by sand- blasting, Whistler has engraved evocative images of the countryside: copses and rolling fields, a woodland glade, a signpost and cottage roofs. Beyond a church spire, a glimpse of the sea between hills has the appearance of a chalice. From the pollard- ed 'winter tree', in the right-hand panel, Church window memorial to the poet Edward Thomas and his wife Thomas's helmet and Sam Browne belt hang in tribute to his service in the first world war.

The war memorial outside Whistler's cot- tage window reminded me that war has played a significant role in Whistler's work. A panel at Radley College, in memory of the composer George Butterworth, contains an affecting image of the vast cemetery and Lutyens' memorial arch to the dead on the Somme, seen through the smashed glass of Butterworth's life. He was killed in action 80 years ago, on 5 August 1916.

Whistler, who served as a signals officer in the Rifle Brigade during the second world war, got himself transferred in 1944 in the hope of seeing action, but was disap- pointed. Paintings by his brother Rex, who was killed by a mortar shell within the first hour of going into action, hang on his stu- dio walls. There is a conversation piece at Edith Olivier's, including Lady Ottoline Morrell, Lord David Cecil and Rex him- self; and a memorable, though uncharac- teristic picture entitled 'The Buckingham Road in the Rain'.

Whistler has described Rex's influence on him as 'all-embracing for a while ... [It] did not immediately weaken with his death, but rather strengthened for some years ... an ever-brightening sunset when the sun had disappeared.' I wondered whether his style would have developed as quickly, as a con- trast to his brother, had Rex lived. `I don't know, perhaps not. He wouldn't have want- ed to stop it, but he did have a big influ- ence on me. However, I was just beginning to do different things before his death.' Rex Whistler would have been 90 this year. Laurence has had 50 more years in which to demonstrate his outstanding artis- tic gifts. But it may not be due only to the misfortune of war that his art will be longer remembered.

Previous page

Previous page