Opera

Verdi Festival (Royal Opera House)

Turkish delight

Rupert Christiansen

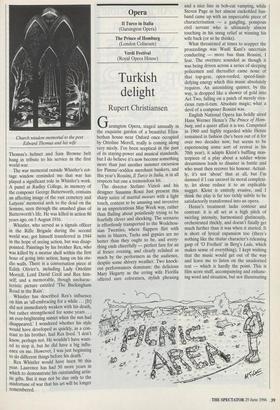

Garsington Opera, staged annually in the exquisite garden of a beautiful Eliza- bethan house near Oxford once occupied by Ottoline Morell, really is coming along very nicely. I've been sceptical in the past of its staying-power and musical standards, but I do believe it's now become something more than just another summer excursion for Pimms'-sodden merchant bankers, and this year's Rossini, 11 Turco in Italia, is in all respects but one a tremendous hit.

The director Stefano Vizioli and his designer Susanna Rossi Just present this sharp satire of marital moeurs with a light touch, content to be amusing and inventive in an unpretentious May Week way, rather than flailing about pointlessly trying to be fearfully clever and shocking. The scenario is effortlessly transported to the Wodehou- sian Twenties, where flappers flirt with twits in blazers, Turks and gypsies are no better than they ought to be, and every- thing ends cheerfully — perfect fare for an al fresco evening, and clearly relished as much by the performers as the audience, despite some shivery weather. Two knock- out performances dominate: the delicious Mary Hegarty as the erring wife Fiorilla offered sure coloratura, stylish phrasing and a nice line in bob-cut vamping, while Steven Page as her almost cuckolded hus- band came up with an impeccable piece of characterisation — a gangling, pompous civil servant who is ultimately almost touching in his smug relief at winning his wife back (or so he thinks).

What threatened at times to scupper the proceedings was Wasfi Kani's uncertain conducting — more bus than Rossini, I fear. The overture sounded as though it was being driven across a series of sleeping policemen and thereafter came none of that top-gear, open-roofed, speed-limit- defying energy which this music absolutely requires. An astonishing quintet, by the way, is dropped like a shower of gold into Act Two, falling on a patch of merely viva- cious rum-ti-turn. Absolute magic; what a devil of a composer Rossini was.

English National Opera has boldly aired Hans Werner Henze's The Prince of Hom- burg, and a queer affair it is too. Composed in 1960 and highly regarded while Henze remained in fashion (he's been out of it for over two decades now, but seems to be experiencing some sort of revival in his 70th year), it adapts Kleist's baffling mas- terpiece of a play about a soldier whose dreaminess leads to disaster in battle and who must then recover his honour. Actual- ly, it's not 'about' that at all, but I'm damned if I can unravel its moral complexi- ty, let alone reduce it to an explicable nugget. Kleist is entirely evasive, and I think the play is far too richly subtle to be satisfactorily transformed into an opera.

Henze's treatment lacks contour and contrast: it is all set at a high pitch of swirling intensity, harmonised glutinously, orchestrated thickly, and doesn't finally get much further than it was when it started. It is short of lyrical expansion too (there's nothing like the titular character's releasing gasp of '0 Freiheit' in Berg's Lulu, which makes sense of everything). I kept wishing that the music would get out of the way and leave me to listen on the unadorned text — which is hardly the point. This is film score stuff, accompanying and enhanc- ing word and situation, but not illuminating or transforming them. Let me pause to pay tribute to Peter Coleman-Wright in the title role, and the committed playing of the orchestra under Elgar Howarth.

That my attention was held to the degree it was (not 100 per cent, I confess) is trib- ute to the magnificent production by Niko- laus Lehnhoff. In my book, Lehnhoff ranks with the very best of his contemporaries, as any sane person who witnessed his Katya Kabanova, Jenufa or The Makropoulos Case at Glyndebourne would surely concur. Like Peter Stein and Luc Bondy (and unlike David Pountney and Richard Jones), he has a genius for focusing on essentials: there's no clutter in his staging, no waste of effect. For The Prince of Homburg, he establishes an atmosphere of hallucinatory blue haze symbolic of the Prince's own mental state. The set is otherwise an aus- tere hall of power, furnished with three tables, but through this haze nothing seems quite real: how much of this is the Prince (or Kleist) merely dreaming? A very queer affair indeed, and one which Lehnhoff and his designer Gottfried Pilz (also responsi- ble for the remarkable lighting) realises with tremendous power. It might have been even more potent, with clearer words, in a smaller theatre: this production was origi- nally mounted in Munich for the tiny Cuvil- liestheater, a quarter of the size of the Coliseum.

Brief notes on the Royal Opera's contin- uing Verdi Festival: in a concert perfor- mance, 11 Corsaro lived up to its reputation as one of Joe Green's feeblest efforts. No grace, little originality (a tenor-soprano duet in Act III momentarily transcends the otherwise pervasive formulas), bags of commonplace energy. But there was a wow of a tenor as the eponymous Byronic hero — Jose Cura, Argentinian, young, hand- some, musically alert and technically secure. Unnecessarily pleading indulgence for a throat infection, he sounded excitingly like a true tenore di forza, a Mario del Monaco for the Millennium, and an Otello in the making.

Written in 1845, three years before Cor- saro but far superior in musical quality, Giovanna d'Arco is a clumsily replotted version of the Joan of Arc story. Covent Garden has really done it proud, however, with a stupendously gorgeous staging by that genius of raise-en-scene Philip Prowse (what that man can do with a black curtain and a lick of gold paint is nothing short of miraculous), and an excellent cast, splen- didly conducted by Daniele Gatti. I have never heard June Anderson (in the title role) sing with such feeling and sensitivity — a touch of tiredness in her once radiant top register seemed a small price to pay for such involvement, and she looked fabulous. The Russian baritone Vladimir Chernov (as her grouchy papa) has a voice of pure red velvet; Dennis O'Neill (as her boyfriend) sounded constipated in contrast. A smashing end-of-term treat, a grand show.

Previous page

Previous page