Press

Good old 'Grauniad'

Bill Grundy

It doesn't seem like twenty years since Mr Alastair Hetherington became editor of the then Manchester Guardian. As a matter of fact, it isn't. It's only nineteen. It was 1956, the year of Suez, the year when half of Britain went mad, and it became hard to resist the conclusion that we were being led by a band of lunatics. Mr Hetherington had taken over a paper which was selling under 200,000. His anti-Suez attitude was so uncompromising that he instantly lost about 80,000 of his customers. His courage was never in doubt from that moment, although one has to admit that the board, who backed him, must have had a lot of guts too. So, just after taking over, his paper was selling about 120,000.

Now, at his retirement, it is selling around 350,000, which is more than the Times. Considered only as a merchandising operation, it is quite remarkable. But it is far more than that. Twenty years ago the Guardian was a provincial paper. True, it had a tremendous reputation, thanks to the ghost of C. P. Scott, but Scott had been long gone — something like twenty-five years—when Mr Hetherington came on the scene. It still had a high moral tone, it still stood for something, although I'm not quite sure what, but it was a very small fish in a very large pond, and it only mattered to those who, having been brought up on it, continued to read it from sheer force of habit. It is now no longer a local paper, it has an international reputation, it is far and away the most well-written of the 'qualities', it knows what it stands for, it looks good, it is full of laughs, most of them intentional, and if it would only nerve itself to strangle the rriri who writes the punning headlines, it would be just about perfect. And all of this must be attributed to Mr Hetherington. To take the decision to drop the word 'Manchester', to transfer the printing to London, and to keep sales going up at a time when most newspaper circulations were going down, is a remarkable achievement.

Mind you, there have been odd sillinesses, most notably at the time of the Rhodesian UDI. You will remember that Mr Jeremy Thorpe, a well-known bomber pilot, wanted to blow up all the railway lines in

Rhodesia — without harming one Rhodesian, of course. The Guardian seemed for a time to be infected by his madness, and it

began to look as though Cross Street was inhabited by a bunch of homicidal maniacs. But the attack wore off and the Guardian hasn't been noticeably dottier than any other paper since.

And it has been readable. I tend to approach the 'qualities' with a heavy heart, with a sense that here is a duty that must be done, but the Guardian has always seemed to me to be written with a lightness of spirit that makes it easy work to read. Again the credit must go to Mr Hetherington. I do not know which of the things I like about the paper are his own invention but he is editor and must therefore begiven the praise, just as, if the paper were rotten, he would get the blame.

Most of us have known for some time that Mr Hetherington, who is so Scottish it hurts, was beginning to feel he would like to return to his native heather. But we assumed that what would happen was that he would retire to some ivory tower in some grove of Academe. Only Private Eye, better-informed than has sometimes been the case, got it right, and scooped Fleet Street with the news that he was going to become Controller, BBC Scotland.

The question exercising us for the last year or two has, of course, been who would succeed our Alastair? Four or five years ago I'd have bet a pound to a penny that it would be Mr John Cole, the Ulster-born deputy editor. Well, I'd have lost my pound. For the new boy is Mr Peter Preston, thirty-six, who for the last three years has been production editor. Mr Preston has had quite a bit of experience; he joined the Guardian from the Liverpool Post twelve years ago, was first a political reporter, then education correspondent, diary editor and became features editor in 1968. He'll need every bit of that experience. These are hard times for the industry, and the Guardian, despite its increasing circulation, is like every other paper in finding it hard going. It does not, of course, make money. Without the Manchester Evening News, which makes enough profit to keep the

Guardian afloat, it would have sunk long ago. But Mr Preston can take heart. When Mr Hetherington took over in 1956 he too was thirty-six, and he too faced hard times. The paper has survived, improved, and prospered. It is therefore not beyond the bounds of possibility that it will do the same under its new editor. As someone who cannot imagine what the mornings would be like without the good old Grauniad, I hope so.

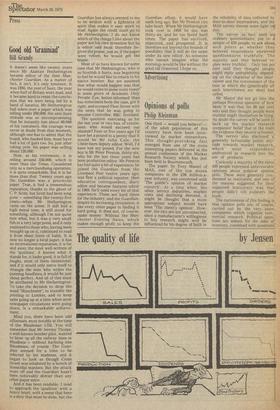

Previous page

Previous page