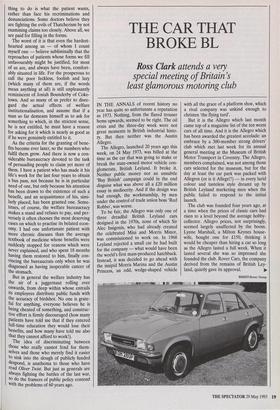

THE CAR THAT BROKE BL

Ross Clark attends a very

special meeting of Britain's least glamorous motoring club

IN THE ANNALS of recent history no year has quite so unfortunate a reputation as 1973. Nothing, from the flared trouser hems upwards, seemed to be right. The oil crisis and the three-day week were not great moments in British industrial histo- ry. But then neither was the Austin Allegro. The Allegro, launched 20 years ago this week, on 24 May 1973, was billed at the time as the car that was going to make or break the state-owned motor vehicle con- glomerate, British Leyland. It broke it. Neither public money nor an unsubtle `Buy British' campaign could in the end disguise what was above all a £20 million essay in mediocrity. And if the design was bad enough, the workmanship, by men under the control of trade union boss 'Red Robbo', was worse.

To be fair, the Allegro was only one of three dreadful British Leyland cars designed in the 1970s, none of which Sir Alec Issigonis, who had already created the celebrated Mini and Morris Minor, was commissioned to work on. In 1968 Leyland rejected a small car he had built for the company — what would have been the world's first mass-produced hatchback. Instead, it was decided to go ahead with the insipid Morris Marina and the Austin Princess, an odd, wedge-shaped vehicle with all the grace of a platform shoe, which a rival company was unkind enough to christen 'the flying turd'.

But it is the Allegro which last month came top of a magazine list of the ten worst cars of all time. And it is the Allegro which has been awarded the greatest accolade: an embrace by a 300-member strong drivers' club which met last week for its annual general meeting at the Museum of British Motor Transport in Coventry. The Allegro, members complained, was not among those cars selected for the museum, but for the day at least the car park was packed with Allegros (or is it Allegri?) — in every lurid colour and tasteless style dreamt up by British Leyland marketing men when the public failed to respond to the initial launch.

The club was founded four years ago, at a time when the prices of classic cars had risen to a level beyond the average hobby- collector. Allegro prices, not surprisingly, seemed largely unaffected by the boom. Lynne Marshall, a Milton Keynes house- wife, bought one for £150, thinking it would be cheaper than hiring a car so long as the Allegro lasted a full week. When it lasted several she was so impressed she founded the club. Rover Cars, the company derived from the remains of British Ley- land, quietly gave its approval.

BMIHT/Ftover Group

`A lot of people have found the Allegro is just the car they want,' she said, as she optimistically laid out 50 or 60 chairs for the AGM in the museum's function room. `It's roomy and comfortable.'

She now has five Allegros in her front garden, one of which is periodically in working order. Her reputation in the Mil- ton Keynes area is such that she has even had a rusty Allegro dumped, like an aban- doned baby, on her driveway.

Her husband, Tony, once had a job as a paint-sprayer in a garage which repaired Allegros. He is now 'spares secretary' for the club.

`To be honest we can't afford a good car,' he said, raising his furrowed, worried brow. 'None of our five Allegros is up to much. But the spares are easy to find. We don't try to defend the car.'

So what exactly was wrong with the Alle- gro, I asked Claire Pollitt, the club's events co-ordinator, who, though still in her mid- 20s, is already on her second Allegro.

`I hate the bootlid,' she said, clasping a clipboard to her chest, 'and the fuse-box tends to get pushed through under the bonnet because it hasn't got a clip.'

`Anything else?'

`And then there were the other odd things like the wheels flying off on the early models.'

Indeed, British Leyland ended up in court after 100 proud new Allegro owners had been overtaken by their own rear wheels. Mechanics had been over-tighten- ing the wheel nuts, which then sheared, leaving the wheels free to roll away on their own.

Other horror stories abound. It was rumoured that the rear window used to fall out if the car was jacked up in the wrong place. One owner is alleged to have been puzzled by a small lump the size of a cigarette packet which stood out from the floor of his boot. One day he poked it: it was a cigarette packet, which an assembly line worker had dropped shortly before the car entered the paint-shop.

The trouble was the workers were hav- ing to build the car too fast,' said Tony Marshall. 'There were always a few nuts and bolts under the carpets because if the workers dropped them it was simplest just to leave them there.'

What compounded the misery was the fact that the Allegro was supposed to be British Leyland's most advanced motor car. When the company was formed by a series of mergers in the late 1960s, it was decided that two parallel ranges of car would be developed: the Morris cars, which would be of conventional design, and the Austin cars, which would be revo- lutionary.

It might have been a cunning marketing ploy, perhaps, had Austin's idea of advanced engineering gone beyond the invention of the square wheel. The sales literature boasted: 'Undoubtedly the fea- ture that will be noticed first is the quartic steering wheel . . . The concern for practi- cality that is a continuing theme through- out the new car has led to this striking departure.'

Officially, the 'quartic' (a misused math- ematical term; the wheel was simply a dis- torted square) steering wheel was there to allow the driver to see the car's instru- ments more clearly. But according to leg- end it was the result of a bored Leyland designer doodling in his office one after- noon; the management picked up on it because it was thought that every car should have its gimmick.

Either way, the square wheel lasted only a year, after complaints by the police who at that time felt obliged to buy British cars. The club members, however, still hanker after the genuine article; excite- ment at the AGM of the Allegro drivers' club mounted when one owner announced he had found an abundant stock of quartic steering wheels in a scrapyard in Learning- ton Spa.

As the room began to fill up with every kind of Allegro spare part — doors and radiator grilles were on offer for a few pounds — I began to read through the original sales literature, painstakingly acquired over the past couple of years by the club archivist, Colin Corke.

The launch of the Allegro was planned as one of the biggest events in British motoring history.

`The Austin Allegro could be called our song for Europe,' boasted George Turn- bull, managing director of the Austin- Morris group, in one brochure.

And it got worse: 'The Allegro is fully equipped to appeal to buyers from the Arctic to the toe of Italy . . . the eye is beguiled by its excellent proportions . . . '

Motoring magazines chose to differ; sev- eral described the vehicle as 'egg-shaped'. Some people claim they can see human expressions in a car; the Allegro seemed to be in some degree of pain.

Corke, an earring-clad Kentish vicar who had once had a job selling Allegros, keenly pointed out the dents and bent bumpers he had found even in the publici- ty photographs. A more embarrassing brochure had been designed for the Ger- man market: it featured caricatures of typ- ical Brits posing beside an Allegro. Above were the words, 'We like British cars.'

With the help of gimmicks and modifi- cations — British Leyland even sold an Allegro with leather and walnut fittings, carrying the badge of Vanden Plas, the coach-builders who fit out Daimler limousines — 650,000 Allegros were finally sold before production ceased in 1982. One was bought by the newly divorced Lord Snowdon. The last one to roll off the pro- duction lines can still be seen, complete with dented roof, at a motoring museum in Gaydon, Warwickshire.

Next year the Allegro drivers' club hopes to celebrate the car's 21st anniversary in style. The matter was discussed at the AGM.

`One member likes the idea of driving through 21 European countries, providing Yugoslavia is open,' said Lynne Marshall. `But we may choose something a little more practical, such as finding a housing estate and naming one of the roads after the car.'

Previous page

Previous page