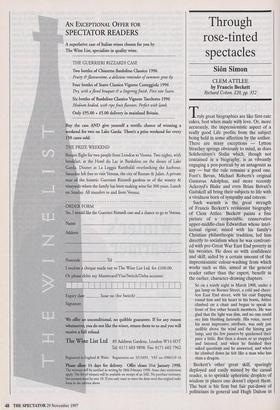

Through rose-tinted spectacles

Sion Simon

CLEM ATTLEE by Francis Beckett Richard Cohen, £20, pp. 352 Truly great biographies are like first-rate cakes, best when made with love. Or, more accurately, the impressionistic aspect of a really good Life profits from the subject being held in some affection by the author. There are many exceptions — Lytton Strachey springs obviously to mind, as does Solzhenitsyn's Stalin which, though not contained in a biography, is as vibrantly engaging a pen-portrait by an antagonist as any — but the rule remains a good one. Foot's Bevan, Michael Roberts's original Gustavus Adolphus, and more recently Ackroyd's Blake and even Brian Brivati's Gaitskell all bring their subjects to life with a vividness born of sympathy and esteem.

Such warmth is the great strength of Francis Beckett's revisionist biography of Clem Attlee. Beckett paints a fine picture of a respectable, conservative upper-middle-class Edwardian whose intel- lectual rigour, mixed with his family's Christian philanthropic tradition, led him directly to socialism when he was confront- ed with pre-Great War East End poverty in his twenties. He does so with confidence and skill, aided by a certain amount of the impressionistic colour-washing from which works such as this, aimed at the general reader rather than the expert, benefit in the earlier, character-drawing chapters.

So on a windy night in March 1908, under a gas lamp on Barnes Street, a cold and cheer- less East End street, with his coat flapping round him and his heart in his boots, Attlee climbed on a chair and began to speak in front of five other branch members. He was glad that the light was dim, and no one could see him blushing furiously. His voice, never his most impressive attribute, was only just audible above the wind and the hissing gas lamp, and the few passers-by quickened their pace a little. But then a dozen or so stopped and listened, and when he finished they asked questions and he answered, and when he climbed down he felt like a man who has slain a dragon.

Beckett's other great skill, sparingly deployed and easily missed by the casual reader, is to sprinkle aphoristic droplets of wisdom in places one doesn't expect them. The best is his firm but fair put-down of politicians in general and Hugh Dalton in particular. In reply to Dalton's assertion that 'Attlee is a small person, with no personality', Beckett says,

Dalton was wrong. Clem was quietly clever and ruthless, while most political leaders, especially Dalton, are noisily clever and ruth- less.

He is also very good with stereotypes: Even today, occasionally, trade union officials model themselves on Bevin: tough and noisy, full of bravado and a kind of sim- ple cunning; conspiratorial and supremely egotistical, but inspired by a passion for jus- tice; crudely bullying yet socially conservative and conformist, with a precise view of the correct behaviour for, and dignity of, a Labour and trade union leader.

Just so. And Beckett's life of Attlee is full of such commonplace but useful insights. The best thing about Beckett is his sure- ness when dealing with the spirit, the con- text, the background of the Labour movement. In matters such as the above characterisation, he is as spot-on as one would expect from a man who grew up in the movement.

Which leads us on to Francis Beckett's strangest decision. He writes in some detail and very evocatively about Attlee's first agent, John Beckett, who went on to become Labour MP for Gateshead after the war and then to join the fascists as Sir Oswald Mosely's propaganda director. Indeed he writes about him so well that John Beckett leapt off the page for me as the most interesting character in the book. This led to me discovering that John Beck- ett was Francis Beckett's father. If he was half the man Beckett fi/s describes, then it must have been a fantastic childhood. But it strikes me as bizarre to write about one's father in this way without mentioning any connection whatsoever.

Which hints at the first of the book's two major weaknesses: uncertainty of scholar- ship and of judgment, which intertwine themselves around the neck of Beckett's revisionist thesis, to strangle it.

In terms of judgment, the most startling- ly inaccurate assessment, incidental though it may appear, is Beckett's view of Attlee's poetry as not great, but not bad. In fact it is excruciatingly awful. Beckett describes Timehouse' as 'one of his earliest and best':

In Limehouse, in Limehouse today and every day, I see the weary mothers who sweat their souls away, Poor, tired mothers trying To hush the feeble crying Of little babies dying For want of bread today.

Beckett says

It has the sentimentality of much socialist writing, but the appalling suddenness of the line 'Of little babies dying' is designed to take the reader by the throat; it would be a cold fish on whom it could fail to have effect.

Well, call me a frozen tilapia, but Attlee's is the worst poetry of any kind I have ever read. It defies belief that a man so highly and classically educated, who professed a deep love of art, poetry and the Italian Renaissance, could write so much verse without contriving a single original phrase or arresting metaphor. Beckett is right that `Limehouse' is Attlee on top poetic form, but 'best' can never be the superlative for his poetry. Only his amusingly self-aggran- dising limerick, of anything Beckett quotes, has any merit whatsoever:

Few thought he was even a starter.

There were many who thought themselves smarter.

But he ended PM, CH and OM, An earl and a knight of the garter.

Beckett quotes this with some embarrass- ment, and Gerald Kaufman — a politician with a deeply held sense of his own impor- tance if ever there was one — rather humourlessly attacked Attlee for it in a recent review. I think it is very funny, and one of the most revealing statements about the essentially vainglorious nature of politi- cians.

Beckett's attitude to the poetry is not as peripheral as it might seem. One cannot help but conclude that the author's probably perfectly active critical faculties are impaired in this instance by his admiration for his subject — a flaw which unfortunately also manifests itself in the body of the book.

Beckett's prime concern is to take issue with the received wisdom that Attlee was an 'accidental' Labour leader and thus prime minister. The standard argument is that because Attlee was the only main- streamer to survive Labour's electoral nemesis (in the person of Ramsay Mac- Donald) of 1931, so he had a head start over his more talented rivals — Dalton and Morrison in particular — which they could never catch up with. From this it follows that Attlee's successes, the 1945 landslide and the government's titanic achievements, were not really his, but would have accrued, probably in greater measure, to any other Labour leader.

Disproving this hypothesis is the central theme of Beckett's book. Obviously, there can be no end to such counter-factualism. All one can say is that, while he makes the point as forcefully as possible, Beckett is ultimately not convincing.

He is not helped by his own admission of the fragility of his scholarship. Of Attlee's support for MacDonald's 1931 Anomalies Act in the face of a concerted socialist cam- paign by Jimmy Maxton's ILP, Beckett says, 'Clem Attlee must in his heart have agreed with the ILP' and 'It may have been — almost certainly was — a decision he subsequently regretted.' But he offers abso- lutely no evidence whatsoever. Indeed all the evidence of Attlee's every written word and deed points in the opposite direction. There is probably much truth in Beckett's view, but his argument suffers from his love. The reader, as so often in this book, can be certain that this is what Beckett wants to be the truth, but is no nearer to knowing what mixture it was of ambition, cowardice, loyalty or lack of concern for the poor which really held Attlee's tongue.

The triumph of this work is the author's success in passing on his love for his sub- ject. By the final chapter, which finds an anachronism stoically waiting for death as the Seventies loom, I too liked Attlee, whom I had previously barely known. And I liked the man who brought him to life. But I cannot say I thought Attlee as good a politician as he was a man.

Previous page

Previous page