Exhibitions

Renoir's Portraits: Impressions of an Age (The Art Institute of Chicago, till 4 January)

Renoir revealed

Roger Kimball

The most audacious exhibition on view in the United States at the moment is not in New York but Chicago. And it features not a trans-sexual 'performance artist' doing unspeakable things with bodily fluids but the portrait paintings of the great Impressionist master, Pierre Auguste Renoir (1841-1919). The audacity is of two sorts. One is curatorial. As you enter the handsomely installed exhibition there is a large block of text introducing you to the show. It concludes with a quotation from Renoir announcing that his main ambition is to make 'pretty' pictures.

`Pretty' pictures? At a time when art is supposed to be 'challenging', 'difficult', 'in- your-face', 'transgressive' — anything but beautiful, please, and certainly never mere- ly pretty — it is a daring gesture to adver- tise Renoir's heterodox statement. Renoir is still one of the most popular artists who ever lived. But his very popularity has con- tributed to a steep decline in his critical fortunes. It is extremely easy to sniff at Renoir today, and many obtuse black-clad critics — the same critics who on another day wax ecstatic over the Chapman broth- ers, Damien Hirst, or Vito Acconci — have taken the opportunity afforded by this exhi- bition to say disparaging things about Renoir's art.

Not that there aren't legitimate criticisms to be made about Renoir. He was an immensely prolific artist, and if his best works communicate an enthralling melodi- ousness, he sometimes — and not as infre- quently as one would wish — slouches toward a nervous, heavy sugariness. Per- haps this is what Mary Cassatt felt when she complained about a 1912 exhibition at Durand-Ruel: 'The most awful pictures ... of enormously fat red women with very small heads.'

I suspect Cassatt would revise her opin- ion sharply upward could she see the exhi- bition of Renoir's portraits on view at the Art Institute in Chicago. All the heads in this compact exhibition of 60-odd paintings are well-proportioned and none of the women is distressingly adipose. In fact, most viewers will find this exhibition a rev- elation. Renoir's extreme popularity has made his work seem tediously familiar. This familiarity has formed a carapace, concealing a painter of powerful accom- plishment and beguiling charm. One of the real accomplishments of this exhibition is to retrieve for us the deep painterly audaci- ty of Renoir at his most ambitious.

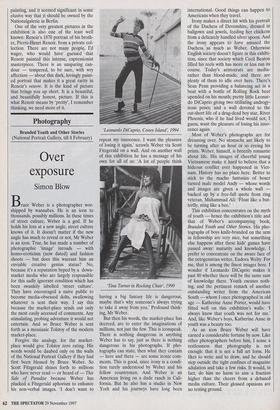

What makes that audacity hard for many of us to appreciate is its essentially sunny nature. Renoir's painting is celebratory; he looked upon the world with an 'oeil bien- veillant', glorying in its sumptuousness. There is great intensity in some of Renoir's portraits, but very little melancholy. The dominant mood is festive: a happy, sociable sensuousness. This side of Renoir is abun- Renoir's 'Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1880-81, the Phillips Collection dantly represented here with such famous pictures as 'Dance at Bougival' (1883), `Mademoiselle Marie-Therese Durand- Ruel Sewing' (1882), and the Phillips Col- lection's spectacular 'Luncheon of the Boating Party' (1880-81), one of Renoir's greatest masterpieces.

Such pictures will be familiar to many viewers; but seeing them again in this exhi- bition brings them to life in a new way. Colin Bailey, the curator, has selected works from throughout Renoir's career that show him at his most lucid and harmo- nious. There is a forceful clarity to Renoir's best work that this exhibition manages to isolate and amplify, with the result that even the most familiar pictures take on a new luminousness, transforming what is undeniably 'pretty' into something statelier and more substantial. What Bailey said about Renoir's work in the 1860s holds good for his entire career: 'Renoir is a ten- der Realist, whose observation of aspects of urban and suburban leisure, while keen, is also kind.'

There are many high points to this exhi- bition. Other familiar paintings include the commanding 'Madame Georges Charpen- tier and Children' (1878) and 'Riding in the Bois de Boulogne' (1873). Among other things, these paintings show that in aiming to make 'pretty' pictures Renoir did not necessarily sentimentalise or diminish women through daintiness. Mme Charpen- tier is sharp, tough, motherly, forbidding yet still gracious, while the depiction of an army officer's wife and her young son rid- ing in the Bois de Boulogne is a picture of extraordinary polish and unsprung tension. In fact, Renoir excelled in portraying frank, competent women: the late, affectionate portrait of his wife and her dog, 'Madame Renoir and Bob', shows a handsome matron in a loose, peasant shift coolly assessing the viewer — as certain of him, one feels, as she is of herself. (`My mother,' Jean Renoir later recalled, 'brought a great deal to my father: peace of mind, children whom he could paint, and a good reason not to go out in the evening.') There are many delights in this exhibi- tion. There are also a few surprises. The extraordinary portrait of the dealer Ambroise Vollard dressed as a toreador, for example. Painted in 1912, it was Renoir's last portrait, and one of his best. At first it seems almost comical: the distin- guished dealer in this decidedly uncharac- teristic costume seems slightly preposterous. But there is a ferocity in Renoir's portrayal that animates the pic- ture, giving a solidity and depth far beyond what one at first expects.

Probably the strangest picture on view is `Children's Afternoon at Wargemont', from 1884, which presents a tableau of a mother and her two daughters. Painted with an unusual flatness and psychological edge, it looks forward to Balthus, minus the explicit paedophilia and voyeurism. It is an extraordinarily arresting, almost creepy painting, and it seemed significant in some elusive way that it should be owned by the Nationalgalerie in Berlin.

One of the very greatest pictures in the exhibition is also one of the least well known: Renoir's 1870 portrait of his broth- er, Pierre-Henri Renoir, from a private col- lection. There are not many people, I'd wager, who would have guessed that Renoir painted this intense, expressionist masterpiece. There is an unsparing can- dour — tempered, to be sure, with wry affection — about this dark, lovingly paint- ed portrait that makes it a great rarity in Renoir's oeuvre. It is the kind of picture that brings you up short. It is a beautiful, and beautifully honest, picture. If this is what Renoir means by 'pretty', I remember thinking, we need more of it.

Previous page

Previous page